The Duke set down his valise, and as he did so a door opened at the back of the house, and a stout landlady Issued forth. She greeted the Duke civilly, but sharply, saying: “Good day, sir, and what may I do for you?”

“I should like to hire a room, if you please,” said the Duke, with his gentle dignity.

Her eyes ran over him. “Yes, sir. How long would you be staying, if I may ask?”

“I am not perfectly sure. A day or two, perhaps.” Her quick scrutiny having taken in every detail of the quiet elegance which characterized his dress, she directed her gaze to his face. She seemed to like what she saw there, and allowed her features to relax their severity. She said, still briskly, but in a tone that held a hint of motherliness: “I see, sir. A nice front bedchamber you would like, and a private parlour, I daresay. You won’t care to be sitting in that noisy coffee-room.”

The Duke thanked her, and said that he thought he should be glad of the parlour.

“Come from London on the coach, sir?” said Mrs. Appleby. “Nasty racketing things they be! Shaking all your bones together until you’re fair wore-out with holding on to the side to stop yourself falling off. I can see you’re tired, sir: you look downright bagged!”

“Oh, no!” Gilly said, blushing faintly. “I have just a touch of the headache, that is all.”

“I’ll fetch you up a pot of tea directly, sir, for there’s nothing like it, and I’ve a kettle right on the boil at this very moment. Myself, I could never abide the way those coaches sways over the road: it makes a body’s stomach rise up against them, and that’s the truth. Polly! Ned! Take up the young gentleman’s bag to No. 1, Ned; and you, my girl, get some kindling and set a fire going in the Pink Parlour! Bustle about, now! Don’t stand there gawping!”

“Thank you, but I shan’t need a fire: it is quite warm,” said Gilly.

“You’ll be more comfortable with a bit of a blaze in the grate, sir,” said Mrs. Appleby firmly. “Very treacherous these autumn days are, and you don’t look very stout to me, if you will pardon the liberty. But no need to be afraid of damp sheets in my house, and if you should happen to fancy a hot posset going to bed you have only to pull the bell, and I shall brew it for you, and with pleasure.”

The Duke perceived suddenly that he had escaped from Nettlebed only to fall into the clutches of Mrs. Appleby, and gave an involuntary laugh. Mrs. Appleby smiled kindly at him, and said: “Ah, you’re feeling better now your stomach’s beginning to settle, sir! I’ll take you up to your bedchamber. And what name would it be, if you please?”

“Rufford,” replied Gilly, choosing one of his titles at random. “Mr. Rufford.”

“Very good, sir, and mine is Appleby, if you should want to call me at any time, which I beg you will do if there is anything you would like. This way, if you’ll be so good!”

He followed her upstairs to a dimity-hung room overlooking the street. The furniture was all old-fashioned, but everything seemed to be clean, and the bed looked as if it might be comfortable. He laid his hat down, and pressed his hands over his eyes for a moment, before casting off the muffler from round his neck. Mrs. Appleby, observing this unconscious gesture, instantly recommended him to lay himself down upon the bed, and promised to fetch up a hot brick to put at his feet. The Duke, who knew from bitter experience that the only cure for his shattering headaches was to lie in a darkened room, said that he would go to bed for a little while, but declined the hot brick. But Mrs. Appleby reminded him so forcibly of his old nurse that he was not really surprised when she re-entered the room shortly afterwards carrying the promised brick wrapped in a piece of flannel. The boots shortly appeared with a tea-tray; and Polly was sent off to fetch up the vinegar, so that the poor young gentleman could bathe his face with it. With three people ministering to him, the Duke could almost have fancied himself back at Sale House, and although a spiked cartwheel seemed to be revolving behind his eyes, he could not help giving another of his soft laughs. Mrs. Appleby stood over him while he drank his tea, telling him that her son, who was in a very good way of business at Luton, had suffered from Just such sick headaches when he was a lad, but had grown out of them, as Mr. Rufford would doubtless do also. She then drew the curtains across the window, picked up the tea-tray, and departed, leaving Gilly divided between annoyance at his own weakness and amusement at her evident adoption of him.

Chapter IX

Although the Duke’s headache had not quite left him by the time a medley of fragrant odours arising from downstairs announced the dinner-hour to be at hand, it was materially better, and he got up from his bed, and unpacked his valise. By the time he had disposed his belongings in the chest of drawers, his attentive hostess was tapping on the door. He assured her that he was much restored, and she escorted him to a small parlour, where a fire burned, and the table was already spread with a cloth, and laid with some bone-handled knives and forks.

The Duke dined off some small collars, a serpent of mutton, and a boiled duck with onion sauce, and afterwards tried the experiment of lighting one of the cigars he had brought with him. The waiter, who had been about to bring him a spill, watched with deep interest the kindling of a match with Promethean fire from the machine which the Duke carried in his pocket, and ventured to say that he had heard tell of those things, but had never before seen one.

The Duke smiled in his absent way, and asked: “Is there an inn in Baldock called the Bird in Hand?”

“It’s wunnerful what they think of,” said the waiter. “They do tell me they even has gas-lamps in Lunnon nowadays. Bird in Hand, sir? Not in Baldock, there isn’t. Leastways, I never heard tell on it, and it stands to reason I would have if there were sich a place.”

“Perhaps it may be a little way from the town,” suggested Gilly.

“Ah, very likely,” the waiter agreed, beginning to pile up the dishes on a tray. “There’s no saying but what it mightn’t be so.”

“And perhaps,” further suggested Gilly patiently, “there may be someone in the tap-room who may know of it if you were to ask them.”

The waiter said that he would do this, and went away with his tray. He was gone for some time, and when he came back, although he had collected a quantity of information about a Bird in the Bush, a Partridge, and a Feathers Inn, he had not discovered anyone who knew the Bird in Hand. Gilly rewarded him suitably for his efforts, and said that it did not signify. He did not feel equal to pursuing his enquiries further that evening, so when the waiter had withdrawn he stretched his legs out before the fire, and opened the book his cousin Gideon had given him to read upon his travels. The preface somewhat quellingly advertised the work to exhibit “the amiableness of domestic affection, and the excellence of universal virtue,” but Gideon had warned him not to allow himself to be daunted by this unpromising start. The book was anonymously published, and had, of course, been cut up by the Quarterly. It was entitled Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. The Duke blew a cloud of smoke, crossed one foot over the other, and began to read.

The candles were guttering in their sockets, and the fire was burning very low when the Duke at last tore himself from the tale, and went to bed.

He saw, on consulting his watch, that it was past midnight, and when he opened the door of the parlour he found the inn in darkness. Guarding the flame of his bedroom candle with one hand, he trod along the passage, not precisely expecting to meet a man-made monster (for he was no longer a child, he told himself) but with a shudder in his flesh. He must find some indescribably horrible tale to bestow on Gideon, in revenge for his having given his poor little cousin a book calculated to keep him awake all night, he decided, smiling tohimself.

But with every expectation of having his rest disturbed by nightmares, he slept soundly and dreamlessly all night, awaking in the morning to hear cocks crowing, and to find sunlight stealing between the closed blinds of his room. All trace of his headache had left him; he felt remarkably well, and thought there must be something salubrious about the air of Hertfordshire.

He had told the boots he would have his shaving-water brought to him at eight o’clock, but when this worthy came into his room to waken him, he found him standing by the window in his great coat, interestedly watching a herd of bullocks being driven down the street. It seemed to be market-day, and the Duke had never come into close contact with a market before, and consequently found it most entertaining. He turned his head when the boots entered, saying: “Is it market-day? What quantities of pigs and cows and chickens have come into the town! You must have a very large market here!”

“Oh, no, sir!” said the boots pityingly, setting down the jug of water on the corner-washstand. “This ain’t nothing! Missus said to ask if there was anything as you would be wanting.”

“Thank you—if you would be good enough to have my coat brushed!” the Duke said, picking it up, and handing it to him.

The boots bore it off carefully. It seemed a very grand coat to him, made of superfine cloth, and lined with silk. He told the waiter, whom he happened to meet on his way to the boot-room, that he suspicioned No. 1 was a high-up gentleman, one as had come into the world hosed and shod, for he had thrown his good shirt that hadn’t a spot on it on to the floor, and a necktie with it, like as if he meant to put on a fresh one. “Which is a thing, Fred, as none but the nobs does. And what queers me is what brings him to this house!”

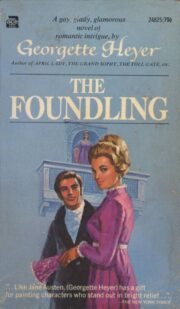

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.