Money presented no difficulties. He had scarcely broken into the hundred pounds Scriven had drawn for him on his bank, so that he would not be forced to arouse suspicion by demanding more. The hardest problem, he soon realized, would be the packing of a valise to take with him.

He had not the smallest notion where his valises and trunks were stored. This was a severe set-back, and he wasted some minutes in trying to think out a way of discovering this vital information before it occurred to him that he could very well afford to buy a new valise. Probably his own bore his cypher upon them: he could not remember, but it seemed likely, since those who ordered such things for him had what amounted to a mania for embossing them either with his crest, or with a large and flourishing letter S.

He would need shirts, too, and his night-gear, and ties, wrist-bands, brushes, combs, razors, and no doubt a hundred other things which it was his valet’s business to assemble for him. He had a dressing-case, and a toilet-battery, but he could not take either of these. Nor could he take the brushes that lay on his dressing-table, for they naturally bore his cypher. And if he abstracted a few ties and shirts from the pile of linen in his wardrobe, would Nettlebed instantly discover their absence, and run him to earth before he had had time to board the coach? He decided that he must take that risk, for although he knew he could purchase soap, and brushes, and valises, he had no idea that it might be possible to purchase a shirt. One’s shirts were made for one, just as one’s coats and breeches were, and one’s boots. But to convey out of Sale House, unobserved, a bundle of clothing, was a task that presented insuperable obstacles to the Duke’s mind. He was still trying to hit upon a way out of the difficulty when Nettlebed came in, and softly drew back the bed-curtains.

The Duke sat up, and pulled off his night-cap. He looked absurdly small and boyish in the huge bed, so that it was perhaps not so very surprising that Nettlebed should have greeted him with a few words of reproof for the late hours he had kept on the previous evening.

“I never thought to see your Grace awake, not for another two hours I did not!” he said, shaking his head. “The idea of Mr. Matthew’s sitting with you for ever, and keeping you from your bed until past three o’clock!”

The Duke took the cup of chocolate from him, and began to sip it. “Don’t be so foolish, Nettlebed!” he said. “You know very well that during the season I was seldom in bed before then, and sometimes much later!”

“But this is not the season, my lord!” said Nettlebed unanswerably. “And what is more you was often very fagged, which his lordship observed to me when we left town, and it was his wish you should recruit your strength, and keep early hours, and well I know that if he had been here Mr. Matthew would have been sent off with a flea in his ear! For bear with Mr. Matthew’s tiresome ways his lordship never has, and never will! And I think it my duty to tell you, my lord, that the piece of very gratifying intelligence your Grace was so obliging as to inform me of last night, in what one might call a confidential way, is known to the whole house, including the kitchenmaids, who have not above six pounds a year, and do not associate with the upper servants!”

“No, is it indeed?” said the Duke, not much impressed, but realizing from long experience that Nettlebed’s sensitive feelings had received a severe wound. “I wonder how it can have got about? I suppose Scriven must have dropped a hint to someone.”

“Mr. Scriven,” said Nettlebed coldly, “would not so demean himself, your Grace, being as I am myself, in your Grace’s confidence. But what, your Grace, am be expected, when—”

“Nettlebed,” said the Duke plaintively, “when you call me your Grace with every breath you draw I know I have offended you, but indeed I had no notion of doing so, and I wish you will forgive me, and let me have no more Graces!”

His henchman paid not the least heed to this request, but continued as though there had been no interruption. “But what, your Grace, can be expected, when your Grace scribbles eight advertisements of your Grace’s approaching nuptials, and leaves them all on the floor to be gathered up by an under-servant who should know his place better than to be prying into your Grace’s business?”

“Well, it doesn’t signify,” said the Duke. “The news will be in tomorrow’s Gazette, I daresay, so there is no harm done.”

Nettlebed cast him a look of deep reproach, and began to lay out his raiment.

“And I told you of it myself,” added the Duke placatingly.

“I should have thought it a very singular circumstance, your Grace, had I learnt it from any other lips than your Grace’s,” replied Nettlebed crushingly.

The Duke was just about to apply himself to the task of smoothing his ruffled sensibilities when he suddenly perceived how Nettlebed’s displeasure might be turned to good account. While Nettlebed continued in a state of umbrage, he would hold himself aloof, and without neglecting any part of his duties would certainly not hover solicitously about him. He would become, in fact, a correct and apparently disinterested servant, answering the summons of a bell with promptitude, but waiting for that summons. In general, the Duke took care not to permit such a state of affairs to endure for long, since Nettlebed could, in a very subtle way, make him most uncomfortable. Besides, he did not like to be upon bad terms with his dependants. Lying back against his pillows, he considered the valet under his lashes, knowing very well that Nettlebed was ready to accept an amend. Nettlebed had just laid his blue town coat tenderly over a chair, and was now giving a final dusting to a pair of refulgent Hessian boots. The Duke let him finish this, and even waited until he had selected a suitable waistcoat to match this attire before—apparently—becoming aware of his activities. He yawned, set down his cup, and said: “I shall wear riding-dress today.”

At any other time, such wayward behaviour in one whom he had attended since his twelfth year would have called from Nettlebed a rebuke. He would, moreover, have entered into his master’s plans for the day, and have sent down a message to the stables for him. But today he merely folded his lips tightly, and without uttering a word restored the town raiment to the wardrobe.

This awful and unaccustomed silence was maintained throughout the Duke’s toilet. It was only broken when the Duke rejected the corbeau-coloured coat being held up for him to put on. “No, not that one,” said the Duke indifferently. “The olive coat Scott made for me.”

Nettlebed perceived that this was deliberate provocation, and swelled with indignation. Scott, who made Captain Ware’s uniforms, and was largely patronized by the military, was an extremely fashionable tailor, but the Duke’s father had never had a coat from him, and Nettlebed had disliked the olive coat on sight. But he only permitted himself one glance of censure at his master before bowing stiffly, and turning away.

“I shall be out all day, and don’t know when I may return,” said the Duke carelessly. “I shan’t need you, so you may have the day to yourself.”

Nettlebed bowed again, more stiffly than ever, and assisted him to shrug himself into the offending coat. The Duke pulled down his wrist-bands, straightened his cravat, and went down to the breakfast-parlour, feeling very like his own grandfather, who was widely reported to have been a harsh and exacting master, who bullied all his servants, and thought nothing of throwing missiles at any valet who happened to annoy him.

But his cruelty attained its object. When he ventured to go upstairs again to his bedchamber there was no sign of Nettlebed. The Duke trod over to his wardrobe, and opened it. He seemed to have so many piles of shirts stacked on one of the shelves that he thought it unlikely that Nettlebed would notice any depredations, provided he took a few from each pile. He took six, to be on the safe side, and began to hunt for his nightshirts and caps. By the time he had made a selection amongst these, and had added a number of ties, and other necessaries, to the heap on the bed, this had assumed formidable proportions, and he surveyed it rather doubtfully. By dint of asking an incurious under-footman for it, he had been able to procure some wrapping-paper and a ball of twine without incurring question, but he began to think that it was not going to be an easy task to tie up all these articles of apparel into a neat bundle. He was quite right. By the time he had achieved anything approaching a tolerable result he was slightly heated, and a good deal exasperated. And when he looked dispassionately at his bundle he realized that it would be quite impossible for him to walk out of his house carrying such a monstrous package. Then he bethought him that if he did not leave his house quickly he would very likely fall into the clutches of Captain Belper, and fright sharpened his wits. He sent for his personal footman, that splendid fellow who did not care a fig for what might become of him. When the man presented himself, he waved a careless hand towards the bundle, and said: “Francis, you will oblige me, please, by carrying that package round to Captain Ware’s chambers, and giving it into his man’s charge. Inform Wragby that it contains—that it contains some things I promised to send Captain Ware! Perhaps I had best send the Captain a note with it!”

“Very good, your Grace,” said Francis, with a gratifying lack either of surprise or of interest.

The Duke pulled out his tablets from his pocket, found a pencil, and scrawled a brief message. “Gideon,” he wrote, “‘pray keep this bundle for me till I come to you this evening. Sale.”He tore off the leaf from his tablets, twisted it into a screw, and gave it to Francis. “And, Francis!” he said, rather shyly.

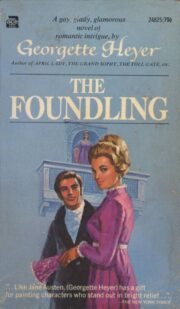

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.