“Thank you!” said the Duke.

“Oh, well, there’s no saying! he might have taken your fancy! What made you take this bolt to the village, my tulip? You did not come merely to offer for Harriet!”

“That, and to buy a horse—not your horse.”

“Gilly, you skirter! Don’t try to come Tip-Street over me! If you have run away from that devilish uncle of yours, I don’t blame you! The most antiquated old fidget I ever saw! Quite gothic, my dear fellow! I’m frightened to death of him. I don’t think he likes me above half.”

“Not as much,” replied Gilly. “In fact, I think he classes you with park-saunterers, and other such ramshackle persons.”

“No, no, Gilly, upon my word! Always in the best of good ton!” protested his lordship. “Park-saunterers be damned! I’ll tell you what, my boy! I’ll take you along to a place I know of in Pickering Place after dinner. All the crack amongst the knowing ones, and the play very fair.”

“French hazard? You know I haven’t the least taste for gaming! Besides, I’m going to visit my cousin Gideon.”

Lord Gaywood exclaimed against such tame behaviour, but the Duke remained steady in refusing to accompany him to his gaming-hell, and they parted after dinner, Gaywood crossing the street to Pickering Place, and the Duke going off to Albany, where Captain Ware rented a set of chambers. These were on the first floor of one of the new buildings, and were reached by a flight of stone stairs. The Duke ran up these, and knocked on his cousin’s door. It was opened to him by a stalwart individual with a rugged countenance, and the air and bearing of an old soldier, who stared at him for an instant, and then exclaimed: “It’s your Grace!”

“Hallo, Wragby! is my cousin in?” returned the Duke, stepping into a small hall, and laving his hat and cane down upon the table.

“Ay, that he is, your Grace, and Mr. Matthew with him,” said Wragby. “I’ll warrant hell be mighty glad to see your Grace. I’ll take your coat, sir.”

He divested the Duke of it as he spoke, and would have announced him had not Gilly shaken his head, and walked without ceremony into his cousin’s sitting-room.

This was a comfortable, square apartment, with windows giving on to a little balcony, and some folding doors that led into Captain Ware’s bedchamber. It was lit by candles, a fire burned in the grate, and the atmosphere was rather thick with cigar-smoke. The furniture was none of it very new, or very elegant, and the room was not distinguished by its neatness. To the Duke, who rarely saw as much as a cushion out of place in his own residences, the litter of spurs, riding-whips, racing-calendars, invitation-cards, pipes, tankards, and newspapers gave the room a charm all its own. He felt at his ease in it, and never entered it without experiencing a pang of envy.

There were two persons seated at the mahogany table, at which it was evident they had been dining. One was a fair youth, in a very dandified waistcoat; the other, a big, dark young man, some four years older than the Duke, who lounged at the head of the table, with his long legs stretched out before him, and one hand dug into the pocket of his white buckskins. He had shed his scarlet coat for a dressing-gown, and he wore on his feet a pair of embroidered Turkish slippers. It was easy to trace his relationship to Lord Lionel Ware. He had the same high nose, and stern gray eyes, and something of the same mulish look about his mouth and chin, which made his face, in repose, a little forbidding. But he had also an attractively crooked smile, which only persons for whom he had a fondness were privileged to see. As he looked up, at the opening of the door, his eyes narrowed, and the smile twisted up one side of his mouth. “Adolphus!” he said, in a lazy drawl. “Well, well, well!”

The fair youth, who had been staring a little moodily at the dregs of the port in his glass, started, and looked round, as much as he was able to do for the extremely high and starched points of his shirt-collar. “Gilly!” he exclaimed. “Good God, what are you doing in town?”

“Why shouldn’t I be in town?” said the Duke, with a touch of impatience. “If it comes to that, what brings you here?”

“I’m on my way up to Oxford, of course,” said his cousin. “Lord, what a start you gave me, walking in like that!”

By this time, the Duke had taken in all the glories of his young cousin’s attire, which included, besides that amazingly striped waistcoat, an Oriental tie of gigantic height, a starched frill, buckram-wadded shoulders to an extravagantly cut coat, buttons the size of crown pieces, and a pair of Inexpressibles of a virulent shade of yellow. He closed his eyes, and said faintly: “Gideon, have you any brandy?”

Captain Ware grinned. “Regular little counter-coxcomb, ain’t he?” he remarked.

“I thought you had a Bartholomew baby dining with you,” said Gilly. “Matt, you don’t mean to go up to Oxford in that rig? Oh, my God, Gideon, will you look at his pantaloons? What a set of dashing blades they must be at Magdalen!”

“Gilly!” protested Matthew, flushing hotly. “Because you are never in the least dapper-dog yourself you need not quiz me! It’s the pink of the fashion, bang up to the nines! You should have a pair yourself!”

“Above my touch,” said the Duke, shaking his head. He looked up at Gideon, who had dragged himself out of his chair, and now stood towering above him, and smiled. “Gideon,” he said, with satisfaction. “Oh, I think I was charged with a great many messages for you, but I have forgot them all!”

“Do you mean to tell me, Adolphus, that you have slipped your leash?” demanded Gideon.

“Oh, no!” said Gilly, sighing. “I did think that perhaps I might, but I was reckoning without Belper, and Scriven, and Chigwell and Borrowdale, and Nettlebed, and—”

“Enough!” commanded Gideon. “This air of consequence ill becomes you, my little one! Is my revered father in town?”

“No, I am alone. Except, of course, for Nettlebed, and Turvey, and—But you don’t like me to puff off my state!”

“This,” said Gideon, lounging over to the door, and opening it, “calls for a bowl of punch! Wragby! Wragby, you old rascal! Rum! Lemons! Kettle! Bustle about, man!” He came back to the fire. “Tell me that my parents are well, and then do not let us talk about them any more!” he invited.

“They are very well, but I am going to say a great deal to you about your father. I think I came for that very purpose. Yes, I am sure that I did!”

“You have never given Uncle Lionel the bag?” exclaimed Matthew.

“Oh, no! He saw me off with his blessing, and an adjuration to visit the dentist. I have never yet succeeded in giving anyone the bag,” said Gilly.

Gideon looked at him under his brows. “Hipped, Adolphus?” he said gently.

“Blue-devilled!” replied the Duke, meeting his look.

“What a complete hand you are, Gilly!” said Matthew impatiently. “I only wish I stood in your shoes! There you are, your pockets never to let, everything made easy for you, all the toad-eaters in town ready to serve you, and you complain—”

“Peace, halfling!” interrupted Gideon. “Sit down, Gilly! Tell me all that is in your mind!”

“Too much!” said the Duke, sinking into a chair at the table. “Oh, that reminds me! Would you like to offer me your felicitations? You won’t be quite the first to do so, but—but you won’t care to be backward! I have this day fulfilled the expectations of my family—not to mention those of every busybody in town—and entered upon a very eligible engagement. You will see the notice in the Gazette, presently, and all the society journals. I do hope Scriven will not forget any of these!”

“Oh!” said Gideon. He pitched the butt of his cigar into the fire, and cast another of those shrewd, appraising looks at the Duke. “Well, that certainly calls for a bowl of punch,” he said. “Harriet, eh?”

The Duke nodded.

“I don’t wish to enrage you, my little one, but you have my felicitations. She will do very well for you.”

The Duke looked up quickly. “Yes, of course! What a fellow I am to be talking in such a fashion! Don’t regard it! She is everything that is amiable and obliging.”

“Well, I’m sure I wish you very happy,” said Matthew. “Of course we all knew that you were going to offer for her.”

“Of course you did!” agreed Gilly, with immense cordiality.

“Charlotte has contracted an engagement too,” observed Matthew. “Did you know it? It is to Alfred Thirsk.”

“Certainly I knew it,” replied Gilly. “In fact, I very nearly withheld my consent to the match.”

“Very nearly withheld your consent!” repeated Matthew, staring at him in the liveliest astonishment.

“Well, I had the intention, but, like so many of my intentions, it came to nothing. Your father wrote me a very proper letter, expressing the hope that the alliance met with my approval. Only it does not: not at all!”

Matthew burst out laughing. “Much my father would care! Stop bamming, Gilly!”

“Bamming? You forget yourself, Matt!” Gilly retorted. “Let me tell you that I am the head of our family, and it is time that I learned to assert myself!”

Gideon smiled. “Have you been asserting yourself, Adolphus?”

“No, no, I am not yet beyond the stage of learning! I am so bird-witted, you know, that I can never tell what is asserting myself, and what is putting myself forward in a very pert fashion that will not do at all.”

Gideon dropped a hand on his shoulder, and gripped it, but as Wragby came in just then, with a laden tray, he said nothing. The Duke lifted his own hand to clasp that larger one. “All gammon!” he said jerkily. “I told you I was blue-devilled!”

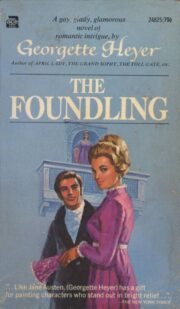

"The Foundling" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Foundling". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Foundling" друзьям в соцсетях.