‘Don’t forget. The little lad. We’ll make a fine monk of him.’

And I laughed through my tears. ‘I’ll send him to you. Unless he has the inclination to be a military man, I will send him to you when he is grown.’

I took the baby in my arms, smiling round at them. Then I looked at Owen, who was looking at me.

‘Let us go home, my husband.’

‘It is my wish, annwyl.’

Owen was restless, a difficult disquiet that took hold of him. I saw it, building day after day, even though he tried for my sake to hide it. Were we not happy? Had we not made for ourselves the life we wished for, when to spend time in each other’s company was ultimate fulfilment, to be apart bleak wilderness?

The death of my mother, Queen Isabeau, touched us not at all, and although we mourned the passing of Lord John with real grief for so great a man, the happenings in London and in France no longer had any bearing on our tranquil existence. But I saw Owen’s frustrations at the end of the day, when we sat alone in our private chamber or relaxed with company after a more formal meal, replete with food and wine, a minstrel singing languorously of times past.

Owen’s gaze turned inward as the plangent notes and tales of heroes and battles wove their glamorous mystery in the chamber, and I knew he was thinking of the days when his forebears had had wealth and status and land. When glory had shone on them and they had fought and won.

Owen, although free, had nothing of his own.

The family lands in Wales had not been restored to him with his recognition under English law: how it rankled with Owen that he had no property in his name, to administer and nurture. No house, no land, nothing to pass down to his heirs with hopes and pride for future generations. How degrading for a man of his birth. Neither was it a good thing for a man’s esteem that he be dependent on his wife.

Oh, he masked it well. He was a master of dissimulation, born of the long years in servitude, but sometimes it rubbed him raw and his eyes were dark with a depth of yearning that I could not plumb.

‘Tell me what eats away at you,’ I begged.

‘It is nothing, my love,’ he invariably replied, the crease between his brows denying his reassurance. ‘Unless you mean our second son’s determination to throw himself under the hooves of every animal in the stables.’

And I smiled, because that was what he wanted me to do. Our son’s obsession with horseflesh had its dangers.

‘Or it may be that I regret my wife not having found the time to favour me with even one kiss this morning.’

So I kissed his mouth, because it pleased him and me.

I might lure him into my bed. I might put before him a plan to drain the lower terrace and build a new course of rooms at Hertford to improve the kitchens and buttery. He would always respond, but his heart was not in it. It was not his own.

Well, it could be put right. I should have seen to it years ago.

I summoned a man of law from Westminster, and consulted with him. And when he saw no difficulty, I had the necessary documents drawn up and delivered into Owen’s hands. I made sure that I was there when they arrived and Owen opened the leather pouch. I watched his face as he read the first of them. As he looked up.

‘Katherine?’ His face was expressionless.

‘These are for you,’ I stated.

I was very uncertain. Would his independence be too great to receive such a gift from a woman, a gift of such value? And yet it was given with all my heart. I wished I could read something in the sombreness of his eyes, in the firmness of mouth and jaw, but I could not, not even after four years of marriage.

‘It is to commemorate the day that we were wed,’ I said, as if it had been a light decision to make the gift. As if it were no more than a pair of gloves or a book of French poetry.

‘It was a bold move, for you to wed me,’ he said. His eyes were on mine, the first documents of ownership still in his hand, the rest yet to be removed from their pouch. ‘To choose a penniless rebel was foolhardy, and yet you did it.’ He smoothed the deed with his hand. ‘Some would say that this is a bold move too.’

I still did not know if he would refuse or accept it with the grace it was given. ‘I consider it a decision showing remarkable business acumen on my part,’ I responded lightly.

And his mouth curved a little. ‘I did not see business dealings as one of your strengths when I wed you, annwyl.’

‘Neither did I.’ I paused. ‘But now I have considered. These are mine. It is my desire that you have them. They need a master to oversee them and ensure their good governance. It would please me.’ I thumped my jewel casket down onto the table—for I had been engaged in selecting a chain of amethysts to wear with a new gown. ‘Stop staring at me and put me out of my misery. Will you accept?’

‘Yes. I will.’ In the end there was no hesitation. ‘Did you think me too arrogant?’

‘It had crossed my mind—yes.’

‘I’ll not refuse so great a gift.’ The smile widened, encompassing me in its warmth. ‘I am honoured.’

And removing the companion documents, he sank to the settle to read through them all. The custody of all my dower lands in Flintshire. I sat beside him. Waited until he had finished and replaced them in their pouch.

‘Well?’

‘I will administer them well.’ ‘I know you will.’

‘Now I have a dowry to provide for a daughter. As well as three fine sons.’

I had carried a girl. Tacinda. A Welsh child with a Welsh name, all dark hair and dark eyes like Owen. Another confirmation of our love.

‘You are a gracious and generous woman, Katherine.’

His kiss was all I could ask for.

I had another motive for giving Owen overlordship of my Welsh dower lands. Our idyll was magnificent—but with a lowering cloud of ominous destruction gathering force on my horizon. Like a sweet peach, full of juice and perfume, but with a grub at the heart that would bring rot and foul decay. How fate laughs at us when we think we have grasped all the happiness that life can offer us.

I was afflicted.

I denied my symptoms at first, hiding them as much from myself as from Owen for they were fleeting moments, soon passed, merely a growing unease, I told myself, brought on by a dose of ill humours as winter approached with its cold grey days and bitter winds. Had I not been so afflicted in the past? I need not concern myself.

Some days, on waking, my mind scrabbled to grip the reality of where I was, what was expected of me. Some days I found myself just sitting, unseeing, without thoughts, not knowing how long I had been so engrossed in nothingness except for the movement of sun and shadow on the floor.

I felt a tension tightening in my chest, like a fist drawing in the slack on a rope, until I feared for my breathing.

And then such feelings receded, my mind snapping back into the present, and I forgot that I had ever been troubled, except for the faint, familiar flutter of pain behind my eyes that laid its hand on me with more frequency. I forgot and pretended that nothing was amiss. Owen and I loved and rode and danced, enjoying the unfettered freedom that had become, miraculously, ours. Had I not experienced such symptoms in the days following Edmund’s conception? Although I had been afraid then, fearing the worst, they had vanished. Would they not do so again?

Our children ran and thrived in the grass beside the river and I watched them.

But then the darkness closed in again. Minutes? Hours? How long it engulfed me I could not tell. I saw it approaching and, leaving my children in the care of Joan or Alice, I took to my room, my bed, pleading weariness or some female complaint as I had done once before to ensure no questions were asked. Only Guille was aware, and she kept her own counsel.

I managed it well.

And what was it that I hid? A space widening in my mind, a vast crater that filled to the brim with dark mist. I did not know what happened around me in those hours. It could be a black billowing cloud, all-encompassing, or a creeping dread, like river water rising, higher and higher, after a downpour. My hands and fingers no longer seemed to be mine. They did not obey my dictates. My lips felt like ice, clear speech beyond me. My servants, my family were as insubstantial as ghosts emerging from an impenetrable mist. I must have eaten, slept, dressed. Did I speak? Did I leave my room? I did not know.

Was Owen aware of my travails? He suspected, even though he was often away, busy now with his own affairs. How could he not know, when I became increasingly detached from him and our world? He said nothing, and neither did I, but I knew he watched me. And perhaps he told Guille to have a care for me, for she was never far from my side.

‘Are you well?’ he asked whenever we met. A harmless enquiry but I saw the concern in his sombre gaze.

I smiled at Owen and touched his hand, the mists quite gone. ‘I am well, my dear love.’

When he took me to his bed, I forgot the whole world except for the loving, secret one we were able to create when I was in his arms. I denied my inner terrors, for what good would it do to bow my head before them? They would engulf me soon enough.

Alice knew, but apportioned the blame for my waywardness, my increased awkwardness to my pregnancy with Tacinda. When I dropped a precious drinking goblet, the painted shards of glass spreading over the floor, splinters lodging in my skirts and my shoes, she merely patted my hand and swept up the debris when I wept helplessly.

Four children in as many years, she lectured. Why was I surprised that sometimes I felt weary, my body not as strong as it might be, my reactions slow? She dosed me on her cure-all, wood betony, in all its forms—powdered root or a decoction of its pink flowers or mixed with pennyroyal in wine—until I could barely tolerate its bitter taste.

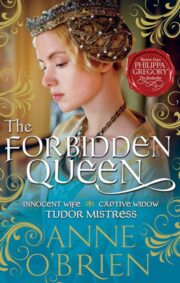

"The Forbidden Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Forbidden Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Forbidden Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.