I would not think of it. I reached out to Owen with my thoughts, opening my mind with all its love and encouragement, and when he tensed a little then glanced in my direction, I knew that he sensed it.

‘It is not dignified that the Queen Dowager be wed to a man who is condemned to live under the force of penal statute, for a crime that he has not committed. That her sons, the brothers of the King of England, must accept that their father is subject to the law as an enemy of the state. I have committed no crime. I have done no wrong. I have served in Sir Walter Hungerford’s household, under our valorous King Henry in France. Yet still I am punished for a rebellion in which I played no part.’

Gloucester, predictably, stood.

‘Are you expecting us to believe that you would not have backed Glyn Dwr’s rising, and wielded a sword against us?’

I held my breath. It was a moot point and we had seen it coming. There was a flash of temper in Owen’s eyes.

Don’t! Don’t retaliate!

It was quickly masked, and I exhaled softly. He would not be shaken from his purpose.

‘No, my lord. I would not have you believe that. I expect, if I had been of an age to fight and hot-headed enough, I would have marched with Glyn Dwr against English forces. But times have changed. The Welsh are at peace. I have a wife and young family to consider. I am no danger to England. Would my wife as Queen Dowager have wed me if I intended to plot and rebel against her son, the Young King? I think she would not. Any man here who would argue the point does not appreciate the utmost respect and loyalty that Queen Katherine maintains towards this kingdom not of her birth.’

A waiting silence fell on the chamber, so strong that it deafened the clamour in my own head. This was for me to fill. From where I sat, I dropped my own words into it.

‘I consider, my lords, that my husband should have the right to own land. And also to own weapons—as does any other man in this kingdom—to protect his family from those who would break the law and attack us. For you should know that twice in recent weeks we have come under duress from armed men. Twice his life has been put at risk.’

‘No!’ Gloucester’s expression was inimical.

‘It is a point to consider.’ In comparison Warwick was courteously bland. ‘But some would say that, even if we are willing to discuss the rescinding of the law in this particular case, it is not appropriate for us to single out this man for so great an honour. A man of less than noble birth—’

It was beautifully done. I thanked Richard with all my heart.

And Owen replied on cue, ‘If my birth is something that you cavil at, my lords—’

‘Your birth, by God.’ Gloucester sprawled in his chair again, glowering across at Warwick, who stared back complacently. How I despised his ill-judged disdain against a man of whom he knew nothing. ‘The Queen Dowager’s dignity. Have we not heard enough, my lords? What dignity did she show when she chose to marry a man no better than a servant from her own household?’

‘It is true I was a servant in the lady’s household,’ Owen replied evenly. ‘It is no secret. But as for my birth, it is as good as any man’s here.’ He paused a little, before addressing Gloucester directly. ‘Even yours, my lord.’

‘Have you gone mad?’ Gloucester responded, leaning forward, hand fisted on his knee.

‘No, my lord, I am not. My descent is a long and honourable one. And I have proof.’

He gestured to Father Benedict, who might be trembling like a reed in a gale but who walked forward to place his document in Gloucester’s hands.

‘As you can trace, my lords,’ Owen advised, while Gloucester unrolled it but barely scanned the contents, ‘my family is high enough to be connected with Owain Glyn Dwr himself. Glyn Dwr was first cousin to my own father, Maredudd ap Tudur.’

‘It is no advantage to be linked with a traitor to the English Crown,’ Gloucester replied.

‘All Welshmen have fought for their freedom through the ages,’ Owen observed carefully. ‘But my ancestry cannot be questioned. My grandmother Margaret came of direct line of descent from Angharad, daughter of Llewellyn the Great, Prince of Gwynedd. His blood is in me, and in my children. I think there is no higher rank that any man could desire. I am honoured to call the Prince of Gwynedd my ancestor. He was defeated by King Edward the First of England but that does not detract from his birth or his legitimate wielding of power over the kingdom of Gwynedd.’

Would it work? Would the argument of Owen’s descent sway them? Unable to remain still, I struggled to my feet to step to Owen’s side, although I did not touch him. We would retain our dignity here.

Warwick, as if it were all new to him, twitched the scroll of genealogy from Gloucester’s hand and observed, ‘It is an impressive argument.’

‘I wish to say one thing, my lords.’

I braced myself at a twinge of discomfort in my belly, but forced myself to speak calmly and surely of a matter I considered very pertinent.

‘The King, whom I have visited, has no difficulty in recognising my sons as his brothers. They are with him now. He has been generous in his gifts to them.’ My heart warmed as I recalled, only a few hours before, Young Henry, kneeling on the floor of his chamber, for once careless of his dignity, graciously donating the little silver ship, which no longer took his interest, to a loudly appreciative Edmund and Jasper.

‘Will they, as sons of their father, continue to be punished as they grow to manhood?’ I held my breath at another inconvenient knotting of my muscles and, abandoning my own dignity, gripped Owen’s arm. ‘Will the brothers of the King be held up before the law as less than English citizens? Will they find no protection from English law? This, my lord, will open them to persecution, as it has my husband, by those who would wish them ill.’ I looked up at Owen. ‘I cannot believe that such an injustice—such a ridiculous travesty—should be allowed to stand.’

We had said all we could.

‘We will give our opinion.’ Gloucester gave nothing away.

And how long would it take them? A lifetime? I did not think I could wait that long.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

How controlled was my reply to Owen. How well I hid the terror that dogged my steps and troubled my dreams. How I wept in the privacy of my bedchamber. Or stormed at the monstrous turn of fate. What woman would not weep or call down curses, when the man she loved was forced to live with an invisible death sentence hanging over his head?

I am a marked man.

And when that woman herself had helped to place the weapon of execution into the hands of the enemy. Enemy. I could think of Gloucester in no other light. Twice Owen had been the target for his revenge. Twice it had failed. But one day, one day the dagger sent and paid for by Gloucester might find its mark.

Guilt stalked me, clawing at my mind, giving me no peace. If I had not carried Owen’s child. If I had not offered myself in marriage to him. If I had not fallen so catastrophically in love with him. How heedless, how thoughtless I had been, swept along in the miracle of our love without consideration of the turbulence it might lead us into, of the blatant threat to Owen that was now unfolding!

Now I saw it all too clearly, pre-empted, so I thought, by Owen standing with me at the coronation of Young Henry in Paris. Nothing could have spoken more clearly to Gloucester that the Queen Dowager had taken an unsuitable man to her bed. It was like striking his cheek with a gauntlet. I had not realised.

There’s nothing that can be done about it, Owen had said.

Was there not? I could not sit and allow Gloucester’s revenge to unfold. My fears for Owen became a rock beneath my heart, yet what could I, a powerless woman, do in the face of royal power?

We must not let Gloucester destroy our happiness.

How could we possibly prevent it? Was it not out of our hands if he chose to send armed men to spill Owen’s blood?

And it came to me, even though I shrank from it. The remedy was in my hands if I had the courage to apply it. My love for Owen was so strong. It held so great a power that it would enable me to step across any chasm, attack any well-defended fortress, challenge even the authority of Gloucester and the Council. I could destroy the threat. All that was required from me was that I make one simple decision.

My breath caught, my heart hammered. Not simple. Not simple at all.

Yet I hugged the knowledge close to me throughout the whole of that endless day. When I had wed Henry, the wilderness of my childhood had provided me with no guiding lines to measure love, to either give or receive it. Now I had travelled its path. I knew love’s glory for myself, and I had my maps and charts to hand. When I closed my eyes, there was Owen in my mind. There in my thoughts was the interplay of two people who adored one another. Who were made for each other. There was the love that would last until death. It gave me the strength to see the truth of what I must do. Yet having seen it, it took me a day and a night of terrifying thought to step to the edge of the chasm, prepared to make the leap.

I found him in the entrance hall, just come in from the stables, handing gloves and hat and an unidentifiable package to one of the pages. His hair was ruffled, his face touched by sun and wind. There had been no attack today.

‘Katherine.’ Owen’s smile, his eyes as they rested on me, spoke to me of joy in reunion. How long a matter of hours apart could seem. We were never apart for long.

I slowed my steps before he could reach me. I must not weaken. No preamble. No warning. I must say it now. I had opened the gates to this marriage with all its rapture, and its unforeseen menace. Now I would close them.

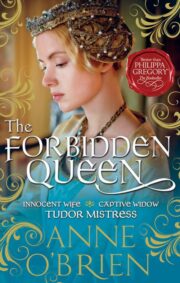

"The Forbidden Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Forbidden Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Forbidden Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.