‘And you dissembled.’

‘I did, and I regret the need. But, truth to tell, it does not do for a man to draw attention to his Welsh lineage.’

It was despicable, shameful. I watched the flattened planes of Owen’s face with anguish, as some of his comments hit home in my heart.

‘Are we watched?’ I asked. ‘Are we spied upon?’ And when he shook his head, ‘Owen, are we—are you—under surveillance?’

‘Yes. There are those who would undo our marriage if they could. They will look for any contravention of the law to hold against us.’

My lips were dry, my throat raw. ‘If you were not wed to me—’ I pulled my hand away when he tried to silence me with his own. ‘If you were not, would anyone care if you wore a sword?’

Owen forced his mouth into a smile of sorts. ‘Probably not. But there’s no point in us second-guessing. It may be that I’m constructing a Welsh mountain out of an English molehill here.’ He pushed himself to his feet, signalling the end to his frank admissions.

‘Now, let us leave Mistress Alice, who keeps frowning at me every time I move, and I will show my honourable wounds to Edmund and Jasper and bask in their admiration.’ He stood slowly, placing his good arm around my waist when I stood too, kissing my cheek in what I recognised as a warning to leave the matter be.

But I knew, as did he, that this was no molehill. My mind refused to abandon the thought that our waylaying on the road had not been some unfortunate accident of time and place. Our attackers had not worn livery, but they had been a force assembled and paid by someone of note. Neither could I push aside from my own mind the terrible burden that Owen had to shoulder, day after day, simply because of his Welsh blood. He had no protection before the law if he was attacked. Would my sons, with their Welsh blood, be equally compromised? I feared that they would.

‘Come and praise my exploits to our sons,’ Owen invited, and I did, knowing when to keep my counsel. Owen was not a man to accept sympathy lightly. His self-esteem would not allow it and so I did not raise the subject again, even when it added a sharp layer of anxiety to my life.

Until the following week. ‘Where have you been?’ I demanded.

I flinched at the shrewish note that rebounded off the walls of living quarters and stabling in the courtyard, but it was born of rampant fear. Owen was late. The short day was now thick with shadows and I had spent the hours since his departure that morning with my mind full of blood and grotesque images. How long did it take a man and a handful of servants to go into Hertford to collect supplies and a consignment of firewood? My imaginings, after the roadside attack, were lively and graphic.

‘It is almost dark. I have been worried out of my mind!’

I tried to moderate the accusation in my tone, but then I saw the state of them, even of Owen, and was forced to absorb what had previously slid under my notice. Why had my husband gone the short distance into Hertford with quite so many henchmen at his back?

‘What happened?’ Without waiting for a reply, I was down the steps and into the chaos of the enclosed space.

Without doubt, there had been foul play. Immediately I was searching for any sign of serious hurt, of wounds as Owen began to organise the unloading of the two wagons, only allowing a breath of relief when I saw there was none, apart from Owen’s shoulder, which still showed traces of stiffness. Yet all of them were the worse for wear, clothes ruined with mud and ill usage. I saw one bloody nose and a gashed forehead.

‘A drunken brawl?’ I observed with commendable calm to cover my thudding heart. And when Owen was taciturn, ‘Are you hurt?’ I asked.

‘No.’ He grimaced.

‘Are you going to tell me what happened?’

‘An incident in the market, my lady,’ the sergeant-at-arms responded to my impatience. ‘We restored the peace right enough, after it got a bit lively. More lively than usual, I’d say. They had weapons. But we put an end to it—with a little show of force.’ He flexed his scuffed knuckles and stretched his shoulders. ‘More than a little, if truth be told.’

I nodded, as if reassured, leaving them to their work, but pounced as soon as Owen stepped into his chamber to strip off his clothes. I was waiting for him, and knew that he wished I were not.

‘Just give me a moment to get out of this gear, Katherine. I’ll join you for supper in a little while.’

I saw the dull tangle of his hair, the thick smear of mud along his side. I thought there might be a graze along his jaw. I heard the anger and weariness in his voice, and I was at his side before he could even loosen his belt. I tilted his chin so that I could confirm my fear then my hands were fisted in urgency in the cloth of his sleeves.

‘Tell me this was a plain market-day accident, Owen.’ I made no attempt to hide the trepidation that beat through my blood. ‘Tell me it was a just a parcel of drunken louts.’

‘It was a drunken brawl over false weights,’ he said briefly. ‘It got out of hand.’

‘As the attack on us last week was pure misfortune.’

He looked at me and I saw resignation grow in his eye, overlaying the glint of anger.

‘Tell me the truth, Owen. Is this ill luck? Or is it a campaign against you?’

He exhaled slowly, and for a moment rubbed his hands over his face, through his hair. ‘What can I say, that you do not already see?’

I released his sleeves, but framed his face with my hands.

‘Will you tell me?’

‘Yes. If you’ll let me get rid of some of this filth.’

He kissed me, pushed me gently away, before proceeding to loosen his belt and drag his tunic over his head, dropping it on the floor. Then he sat to pull off his mired boots, where I knelt beside him. His face was drawn, pinched with a simmering fury, his movements brisk with heavy control. He would not look at me, but I would not be gainsaid.

‘It was not ill luck, was it?’ I nudged his arm.

‘No.’ He dropped a boot on the floor with a thud.

‘Who is responsible? The robbers on the road wore no livery but someone paid them.’

‘I know not,’ Owen snapped, turning his anger on me.

‘I say you do!’

And Owen took the second boot and hurled it at the wall, where it bounced off the stitched forms of a pack of hounds and a realistically bloodied boar, and fell with a thump beside the hearth.

Which outburst of temperament I ignored. ‘You are in danger!’ I accused. ‘And you will not tell me!’

‘Because I can do nothing about it,’ he snarled with none of his usual grace. ‘I have to accept that I am a marked man.’ His words froze on his lips, his eyes lifted to mine for the first time for some minutes.

We stared at each other. My earlier fears leapt into life again, and bit hard.

‘I didn’t mean to say that.’ Owen sighed a little, but the tension was still strong in every muscle of his body.

‘A marked man? What do you mean by that?’ I gripped his good arm as all my anxieties returned fourfold. ‘What else have you not told me? And don’t say that I must not worry. Who says that you are a marked man?’

I had to withstand a difficult pause.

‘Tell me, Owen. You must. You cannot leave me in ignorance of something that affects you and me—and our children.’

And he did, in a flat tone and even flatter words, confirming all that I feared. ‘It’s Gloucester at the bottom of it. Our noble Plantagenet duke. His warning was vicious and intended as a threat. But probably with no real heat in it.’

Which, on present evidence, I did not believe for one minute. Neither, I warranted, did Owen. ‘When we left the Council.’ Now I recalled the incident. ‘He spoke with you, didn’t he? What did he say?’

‘Just that. That I am a marked man.’ Owen’s brow snapped into a black line. ‘No doubt to destroy any pleasure I might gain from successfully seducing the Queen Dowager to my own ends, and enjoying the fruits of her possessions. He said that he would have his revenge, despite the Council’s weak acquiescence. It’s a damnable thing, but there’s nothing can be done to undo it.’ The bitterness in his words increased, and with it the depths of my own grief. ‘I am a Welsh bastard, he observed, and do not know my place. It is Gloucester’s mission to teach me what that place is. With blood and fire if necessary.’

We sat in silence for a moment. The implications of Owen’s confession pressed down on me, until I could do nothing but accept the truth that stared me in the face. I considered it as I rose, collected Owen’s maligned boots and placed them neatly side by side. I stood before him.

‘Are you saying that by marrying me you have put your life in danger?’

Looking up at me, his forearms resting on his thighs, Owen’s brows drew down into an even straighter line. ‘I doubt it’s as extreme as that.’

‘Has our marriage put your life in danger?’ I demanded.

‘Yes. It is possible. But it may be that he intends to teach me a lesson rather than take my life.’

Fear dried my mouth. The child kicked as if it could sense my perturbation.

‘Is there nothing we can do?’

‘Against Gloucester?’ Owen’s brows winged upwards.

‘But the law should protect—’

‘I have no rights before the law,’ he replied gently. ‘You must know that. I am Welsh.’

‘Ah! I had forgotten.’ I lifted my hands in helplessness. ‘I am so sorry.’

Owen stood. As his arms closed around me, as he raised my face so that I must look up, I felt some of the tension in his body leach away at last. And because of that I spoke the one pertinent thought in my mind.

‘When you married me, you opened yourself to danger. And I did not know it. But you knew, didn’t you?’

‘Yes.’

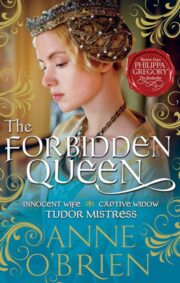

"The Forbidden Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Forbidden Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Forbidden Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.