First St Winifred came between us. Young Henry was fascinated by the story of the virtuous lady, decapitated at the hands of the Welsh Prince Caradoc who had threatened her virtue, followed by her miraculous healing and restoration to life. Young Henry expressed a wish to visit the holy well in the northern fastnesses of Wales. I explained that it was too far.

‘My father went on pilgrimage there. He went to pray before the battle of Agincourt,’ Young Henry said. How had he known that? ‘I wish to go. I wish to pray to the holy St Winifred before I am crowned King.’

‘It is too far.’

‘I will go. I insist. I will kneel at the spring on her special day.’

I left it to Warwick to explain that the saint’s day on the third day of November and young Henry’s coronation on the fifth day would not allow for a journey across the width of the country.

So we celebrated St Winifred at Windsor instead—earlier than her special day—but Owen’s preparations filled Young Henry with the requisite excitement. We prayed for St Winifred’s blessing, commending her bravery and vital spirit, and my coffers bought a silver bowl for Young Henry to present to her. Father Benedict had looked askance at making such a fuss of a Welsh saint—and a woman at that—but if King Henry, the victor at Agincourt, had seen fit to honour her, then so would we.

It was a magnificent occasion.

And then within the day all was packed up and we were heading to Westminster for the crowning of my son. Would Owen and I ever find the opportunity to do more than follow the demands of travel and Court life? It seemed that I would need all of Winifred’s perseverance.

On the fifth day of November I stood beside Young Henry when he was crowned King of England. How ridiculously young he looked at eight years, far too small for the coronation throne. Instead they arranged a chair, set up on a step, with a fringed tester embroidered with Plantagenet lions and Valois fleurs-de-lys to proclaim his importance, and with a tasselled cushion for his feet. Kneeling before his slight figure, I was one of the first to make the act of fealty, wrought by maternal worries.

Pray God he manages to keep hold of the sceptre and orb.

His eyes were huge with untold anxieties when the crown of England was held over his head by two bishops. It was too large, too heavy for him to wear for any length of time, so a simple coronet placed on his brow made a show of sanctity. Henry would have been proud, even more so if his son had not taken off the coronet at the first opportunity during the ceremonial banquet to inspect the jewels in it, before handing it to me to hold, complaining that it made his head ache.

I saw Warwick sigh. My son was very young for so great an honour, but he received his subjects with a sweet smile and well-rehearsed words, before becoming absorbed in the glory of the boar’s head enclosed in a gilded pastry castle.

Owen accompanied me to Westminster, but we may as well have been as far apart as the sun and moon.

And then home to Windsor to mark the ninth anniversary of Young Henry’s birth on the sixth day of December with a High Mass and the feast and a tournament, with opportunities for the younger pages and squires to show off their skills. Henry did not shine, and became querulous when beaten at a contest with small swords.

‘But I am King,’ he stormed. ‘Why do I not win?’

‘You must show your worthiness to be King,’ I reproved him gently. ‘And when you do not, you must be gracious in defeat.’

‘I will not!’

There was little grace in Young Henry and I sensed he would never be the warrior his father had been. Perhaps he would make his fame as a man of learning and holiness. Whatever the future held for my child, as the holy oil was smeared on his brow I felt I had done my duty by my husband, who had in some manner left me, simply by his death, to care for his son. Perhaps I was free now to follow my desire to be with Owen Tudor.

And then it was Christmas and the New Year gift-giving and Twelfth Night.

What of Owen and me?

There was no Owen and me.

After that kiss in the chapel, soft as a whisper on my mouth, we were forced back into the roles of mistress and servant. My cheek healed with no opportunity for a repetition of such an injury. The exigencies of travel, of endless celebrations, an influx of important guests who demanded my time and Owen’s, and the resulting shortage of accommodation all worked against us. Neither of us was at leisure to contemplate even a stolen moment. There were no stolen moments. Edmund might have seduced me at the turn of the stair with hot kisses, but there was no seduction from Owen Tudor. In public Owen treated me with the same grave composure that he had always done.

So how did I survive? How were my nerves calmed when I was close to him, wanting nothing more than to step into his arms but knowing that it could not be until…? Until when? Sometimes I felt we would remain with this harsh distance separating us, like a stretch of impassable and turbulent water, for ever.

And yet there was a wooing, the most tender of wooings from a man who had nothing to give but the wage I paid him, and who could not pin his heart to his sleeve, even if he were of a mood to do so. I suspected that Owen was too solemn for the pinning of hearts.

There was a wooing in those months when we never exchanged a word in private, for I was the recipient of gifts. None of any value, but through them I knew that Owen Tudor courted me as if I were his love in some distant Welsh village and he a fervent suitor. The charm of it wrapped me around for I had no experience of it. Henry had had no need to woo me. I had come to his bed as the result of a signature on a document. Edmund had engaged me in a whirlwind seduction with no time for anything as gentle as courtship. From Owen, it was the small offerings, the simple thought of giving behind them, that took me by surprise and won my heart for ever.

How I treasured them. A dish of dates, plump and exotic, freshly delivered from beyond the seas, sent to me in my chamber. A handful of pippins, stored since the autumn harvest, but still firm and sweet. A fine carp, richly cooked in almond milk, served to me at my table—served only to me—by Thomas my page under orders from Owen. A cup of warm, spiced hippocras brought to my chamber by Guille on a cold morning when rime coated the windows. Had Henry or Edmund even noticed what I ate? Had they considered my likes and dislikes? Owen knew that I had a sweet tooth.

And not only that. My lute was newly and expertly strung by morning—one of the strings having snapped the previous evening—before I had even asked for it to be done. Would Henry have done that for me? I think he would have purchased a new lute. Edmund would not have noticed. When we suffered a plague of mice in the damsels’ quarters, I was recipient of a striped kitten. The mice were safe enough, but its antics made us laugh. I knew where the gift had come from.

Nothing inappropriate. Nothing to cause comment or draw the eye. Except for that of Beatrice, who observed casually one morning when a basket of fragrant apple logs appeared in my parlour, ‘Master Owen has been very attentive recently.’

‘More than usual?’ I queried with a fine show of insouciance.

‘I think so.’ Her eyes narrowed.

And the gestures continued. A rose, icily preserved and barely unfurled. Where had he found that in January? An intricate hood, the leather fashioned and stitched with a pretty tuft of feathers, for my new merlin. I knew whose capable fingers had executed the stitching. And for the New Year gift-giving, a crucifix carved with astonishing precision from that same applewood, polished and gleaming, left for me anonymously and without explanation on my prie-dieu.

And what did I give him? I knew I had not the freedom to give, as he had to me under the cover of the household, but the tradition of rewarding servants at Twelfth Night made it possible. I gave him a bolt of cloth, rich blue damask, as dark and sumptuous as indigo, to be made up into a tunic. I could imagine it becoming him very well.

Owen thanked me formally. I smiled and thanked him for his services to me and my people. Our eyes caught for the merest of breaths then he bowed again and stood aside for others to approach.

My cheeks were aflame. Was no one else aware of the burning need that shimmered in the air between us? Beatrice was.

‘I hope you know what you’re about, my lady,’ she remarked with a caustic glance.

Oh, I did. And after the weeks of thwarted love it could not come fast enough.

‘When can I be with you?’

It was the question I had longed to hear from him.

‘Come to my room,’ I replied. ‘Between Vespers and Compline.’

It was January, bleak and cold, and the court had slipped into its winter regime of survival: keeping warm; tolerating the endless dark when there was no light in the sky when we rose and it had vanished again by supper. But my blood raced hotly. The physical consummation of our love had to be. I wanted to be with him for I loved him with an outpouring of passion I knew not how to express. All I knew was that I loved him and he loved me.

And I had to take Guille into my confidence. She simply nodded as if she knew I could do no other, opening the door for him, closing it without a glance as she left us.

‘I’ll make sure you are not disturbed, my lady,’ she had promised. She did not judge me too harshly.

And there he stood, Owen Tudor, illuminated by a shimmer of candles because, perhaps out of trepidation at the last, I had lit my room as if for a religious rite. Dark-clad, hair dense as the damask I had given him, face sternly glamorous, his presence overwhelmed my bedchamber, and me. But not quite. I knew what I would do.

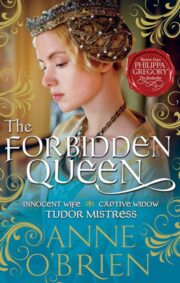

"The Forbidden Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Forbidden Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Forbidden Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.