I must have moved involuntarily, for he let my hand slip from his and retreated one step. Then another. He no longer looked at me, but bowed low.

‘You should return to your chamber, my lady.’

His voice had lost all its immediacy, but I could not leave it like that. I could not walk out of that chamber without another word being spoken between us, and not know…

‘Master Tudor, it would be wrong in a perfect world…to have a personal regard, as we both agree. But…’ I sought again for the words I wanted. ‘In this imperfect world, what does this hapless servant feel for his mistress?’

And his reply was destructively abrupt. ‘It would be unwise for him to tell her, my lady. Her blood is sacrosanct, whilst his is declared forfeit because of past misdemeanours of his race. It could be more than dangerous for the lady—and for him.’

Danger. It gave me pause, but we had come so far…

‘And if the mistress orders her servant to speak out, danger or no?’ I held out my hand, but he would not take it. ‘If she commands him to tell her, Master Tudor?’ I whispered.

And at last his eyes lifted again to mine, wide and dark. ‘If she commands him, then he must, my lady, whatever the shame or disgrace. He is under her dominance, and so he must obey.’

Deep within me a well of such longing stirred. My scalp prickled with heightened awareness. It was as if the whole room held its breath, even the figures in the tapestries seeming to stand on tiptoe to watch and listen.

‘So it shall be.’ I spoke from the calm certainty of that centre of that turbulent longing. ‘The mistress orders her servant to say what is in his mind.’

For a moment he turned, to look out at the grey skies and scudding clouds, the wheeling rooks beyond the walls of Windsor. I thought he would not reply.

‘And would the lady wish to know what is in his heart also?’ he asked.

What an astonishing question. Although the tension in that freezing room was wound as tight as a bowstring, I pursued what I must know.

‘Yes, Master Tudor. Both in his mind and in his heart. The mistress would wish to know that.’

I saw him take a breath before speaking. ‘The mistress has her servant’s loyalty.’

‘That is what she would expect.’

‘And his service.’

‘Because that is why she appointed him.’ I held my breath.

He bowed, gravely. ‘And she has his admiration.’

‘That too could be acceptable for a servant to his mistress.’ Breathing was suddenly so difficult, my chest constricted by an iron band. ‘Is that all?’

‘She has his adoration.’

I had no reply to that. ‘Adoration.’ I floundered helplessly, frowning. ‘It makes the mistress sound like a holy relic.’

‘So she might be to some. But the servant sees his mistress as a woman in the flesh, living and breathing, not as a marble statue or a phial of royal blood. His adoration is for her, body and soul. He worships her.’

‘Stop!’ Shocked, my reply, the single word, lifted up to the rafters, only to be absorbed and made nothing by the tapestries. ‘I had no idea. This cannot be.’

‘No, it cannot.’

‘You should not have said those things to me.’

‘Then the mistress should not have asked. She should have foreseen the consequences. She should not have ordered her servant to be honest.’

His face, still in profile, could have been carved from granite, the formidable brow, the exquisitely carved cheekbones, but I saw his jaw tighten at my denial of what he had offered me. The formality of servant and mistress dropped back between us, as heavy as one of those watchful tapestries, whilst I was still struggling in a mire of my own making. I had asked for the truth, and then had not discovered the courage to accept it. But I had been weak and timid for far too long. I spoke out.

‘Yes. Yes, the mistress should have known. She should not have put her servant at a disadvantage.’ I slid helplessly back into the previous heavy formality, because it was the only way in which I could express what was in my mind. ‘And because she should have been considerate of her servant, it is imperative that the mistress be honest too.’

‘No, my lady.’ Owen Tudor took a step back from me, all expression shuttered, but I followed, astonished at the audacity that directed my steps.

‘But yes. The mistress values her servant. She is appreciative of his skills.’ And before I could regret it, I went on, ‘She wishes he would touch her. She wishes that he would show her that she is made of flesh and blood, not unyielding marble. She wishes he would show her the meaning of his adoration.’

And I held out my hand, a regal command, even as I knew that he could refuse it, and I could take no measure against him for disobedience. It would be the most sensible thing in the world for him to spurn my gesture.

I waited, my hand trembling slightly, almost touching the enamelled links of his chain of office, but not quite. It must be his decision. And then, when it seemed that he would not, he took my hand in his, to lift it to his lips in the briefest of courtly gestures. His lips were cool and fleeting on my fingers but I felt as if they had branded their image on my soul.

‘The servant is wilfully bold,’ he observed. The salute may have been perfunctory, but he had not let go.

I ran my tongue over dry lips. ‘And what, in the circumstances,’ I asked, ‘would this bold servant desire most?’

The reply was immediate and harsh. ‘To be alone, in a room of his choosing, with his mistress. The whole world shut out behind a locked door. For as long as he and the lady desired it.’

If breathing had been difficult before, now it was impossible. I stared at him, and he stared at me.

‘That cannot be…’ I repeated.

‘No.’ My hand was instantly released. ‘It is not appropriate, as you say.’

‘I should never have asked you.’

His eyes, blazing with impatience—or perhaps it was anger—were instantly hooded, his hands fallen to his sides, his reply ugly in its flatness. ‘No. Neither should I have offered you what you thought you wished to know, but had not, after all, the courage to accept. Too much has been said here today, my lady, but who is to know? The stitched figures are silent witnesses, and you need fear no gossip from my tongue. Forgive me if I have discomfited you. It was not my intent, nor will I repeat what I have said today. I have to accept that being Welsh and in a position of dependence rob me of the power to make my own choices. If you will excuse me, my lady.’

Owen Tudor strode from the room, leaving me with all my senses compromised, trying to piece together the breathtaking conversation of the past minutes. What had been said here? That he wanted to be with me. That he adored and desired me. I had opened my heart and thoughts to him—and then, through my lamentable spinelessness, I had retreated and thrust him away. He had accused me of lacking courage, but I did have the courage. I would prove that I did.

I ran after him, out of the antechamber and into the gallery, where he must have been waylaid by one of the pages who was scurrying off as I approached. Even if he heard my footsteps, Owen Tudor continued on in the same direction, away from me.

‘Master Tudor.’

He stopped abruptly, turning slowly to face me, because he must.

I ran the length of the gallery, queenly decorum abandoned, and stopped, but far enough from him to give him the space to accept or deny what I must say.

‘But the mistress wishes it too,’ I said clumsily. ‘The room and the locked door.’

He looked stunned, as if I had struck him.

‘You were right to tell me what was in your heart,’ I urged. ‘For it is in mine too.’ He made no move, causing my heart to hammer unmercifully in my throat. ‘Why do you not reply?’

‘Because you are Queen Dowager. You were wed to King Henry in a marriage full of power and glamour. It is not appropriate that I, your servant—’

‘Shall I tell you about my powerful and glamorous marriage?’ I broke in.

So I told him. All the things I had never voiced to anyone before, only to myself, as I had come to understand them.

‘I met him in a pavilion—and I was awestruck. Who wouldn’t be? That he, this magnificent figure, wanted me, a younger daughter, for his wife. He wooed me with the sort of words a bride would wish to hear. He was kind and affectionate and chivalrous when we first met—and after, of course.’ How difficult it was to explain. ‘But it was all a facade, you see. He didn’t need to woo me at all, but he did it because it was his duty to do so, because he wanted what I brought with me as a dower. Henry was very strong on duty. On appearances.’ I laughed, with a touch of sadness.

‘Did he treat you well, my lady?’

To my horror I could feel emotion gathering in my throat, but I did not hold back. ‘Of course. Henry would never treat a woman with less courtesy than she deserved. But he did not love me. I thought he did when I was very young and naïve, but he didn’t. He wanted my royal blood to unite the crowns and bring France under his control.’

‘It is the price all high-born women have to pay, is it not, my lady?’ He raised a hand, as if he would reach out to me across the space, the tenderness in his voice undermining my resolve to keep emotion in check. ‘To be wed for status and power?’

‘It is, of course. I was too ingenuous to believe it at first.’ I returned in my mind to those biting sadnesses of my first marriage, putting them into words. ‘Henry was never cruel, of course, unless neglect is cruelty. But he did not care. And do you know what hurt most? That when he was sinking fast in his final days, when he knew that death would claim him, he never thought of sending for me. He felt no need to say farewell, or even give me the chance to say goodbye to him. I don’t know why I am telling you all of this.’

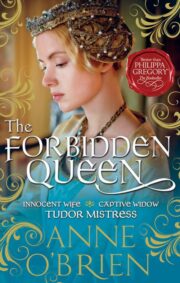

"The Forbidden Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Forbidden Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Forbidden Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.