‘Give the King a beautiful wife. If anyone can change him, can take him away from this passion for Gaveston, Isabella can.’

There was a sense of relief in the room. Warwick was right. Edward was young yet. He was weak; easily influenced, and Gaveston, they all had to admit, was clever.

Marriage was the answer. Beautiful Isabella would save the King.

‘We must impress on the King that he should leave without delay,’ said Arundel.

‘So that,’ went on Lancaster, ‘on his return we can go ahead with plans for the coronation.’

They nodded.

They were convinced— most of them— that Isabella might well make a good husband and father of Edward, and so weaken and, hopefully, destroy the evil influence of Piers Gaveston.

THE QUEEN’S DISCOVERY

THESE were days for the Princess Isabella and she was gratified to be the centre of attention. They were all so pleased about the proposed match; and so was she― for she had heard her bridegroom-to-be was one of the most handsome in the world. She had never seen him but those who had assured her that there had been no exaggeration of his good looks.

‘He is tall,’ they said, ‘with flaxen hair. He is just like his father and he was known in his youth to be a fine-looking man. You will be a Queen,’ they went on. ‘Queen of England― think of that.’

She had thought about it and it pleased her. She patted her luxuriant curls and assured herself that she would be a good match for this handsome man, for she was an acknowledged beauty herself. She had seen even her father’s eyes soften at the sight of her and everyone knew what a ruthless man he was! He was the most powerful King in Europe and her mother had been a Queen in her own right before she had married, so no one could be more highly born than the Princess Isabella.

It was only to be expected that because of her outstanding beauty she would make a grand match.

Her brothers— Louis, who was always quarrelling, Philip, who was tall and aloof and Charles who was so good-looking that they were already calling him Le Bel, a title which in her father’s heyday had been given to him— were pleased with the match. So were her uncles Charles de Valois and Louis d’Evreux. In fact the uncles were to go to England when she and her bridegroom left for his country.

She was glad of that. It would make the parting less acute although of course she had always known that, as a Princess, she would have to leave her home one day. It was the fate of all princesses. It had not worried her unduly, and even though at this time she was barely sixteen years old she was prepared for what life would offer. Her strong-minded mother, who never forgot that she was the Queen of Navarre as well as France, and her ruthless father had endowed her with something of their own natures, and she was quite ready to hold her own position in whatever society she found herself.

She only had to see her reflection to receive assurance and if she could not have seen for herself in her mirror, the eyes of the men at her father’s court told her that without doubt was possessed of a rare attraction.

Five years previously she had been solemnly betrothed to Edward, Prince of Wales. This had taken place in Paris and she remembered it well. The Count of Savoy and the Earl of Lincoln had represented the Prince of Wales and her father had given his blessing and her hand to the heir of England. It had been a very impressive moment when she had placed her hand in that of Père Gill, the Archbishop of Narbonne, who had stood proxy for Edward. From that moment she had known that as soon as she was old enough she would become Edward’s wife. Since then she had tried to learn all she could about Edward. She had discovered that he often disobeyed father and she was amused. Her father had talked of the King of England as that wily old lion and gave the impression he did not by any means love him, although he respected him.

‘We must always be watchful of the old lion,’ he had said, and he was always delighted when the Welsh and the Scots gave his rival trouble. But he was eager for this marriage and so it seemed was the old King of England.

Her mother had explained it to her. ‘Alliances such as you will make with the Prince of Wales are a safeguard of peace. And when you are Queen of England, never forget France.’

She had sworn she never would.

It was comforting too that her aunt Marguerite was the Dowager Queen of England. She was coming to France for the wedding. Jeanne, Isabella’s mother, often talked of Marguerite.

‘Your aunt is a good woman, Isabella. She was happy with the old King.

Marguerite is such a meek and docile woman that she would believe she was happy as long as her husband did not ill-treat her or too blatantly consort with other women. The King of England was a faithful husband and that is considered rare. Therefore your aunt was a very happy wife. She has said so often.’

Isabella was well aware of the story of her aunts. She could just remember beautiful Aunt Blanche who had married into Germany and died soon after.

They had thought that Blanche would marry the King of England at one time— at least the King of England had thought it, but Philip le Bel had had other ideas for his sister and had tricked Edward into taking Marguerite. Isabella reflected that her father could be very wily. She admired him for it, although she supposed some would call it dishonourable.

Isabella had always been a girl to keep her eyes and ears open. She liked to sit at her father’s table— and he liked her to be there because he was proud of her beauty— and she would be alert, listening to talk. It was gratifying to learn that she was the daughter of the most feared man in Europe.

They still called him that although it scarcely fitted now. She had heard that when he had come to the throne at the age of seventeen he had been so handsome that women found it difficult to take their eyes from him. He had a cold nature though and rarely any warmth showed. Sometimes she thought he admired her because she had inherited so many of his characteristics— the most obvious being beauty. He no longer possessed his— he had grown too fat and florid― but if he had lost his looks he had gained in power. Some said he was the most ruthless man in Europe. He was cold, harsh and calculating and the more power he achieved, the more he wanted; and he had few scruples when it came to attaining it. That he was vindictive and completely without mercy was well known. It was one of the reasons why he was so feared. He sought not only to rule France but the whole world and even that did not seem to him an impossible dream.

Isabella knew how pleased he was that Edward of England was kept busy with his border rebels. Of all men, the King of France feared the King of England and Edward’s obsession to bring Wales and Scotland under the English crown was as great as Philip’s dream of complete domination. Edward had died without achieving this success and there was no doubt that her father had looked upon Edward’s death as a happy augury for France.

She had heard him say. ‘This young cub, my son-in-law will give me no trouble. Or if he does, I shall know how to deal with him.’ Then seeing the look in his daughter’s eyes, he had become alert. He added: ‘My daughter will help me, I know, and she is going to be a power in that troublesome kingdom.’

It was flattery of course and a reminder. Never forget you are French, daughter. Always remember where your allegiance lies.

When a Princess married a King and became a Queen his country was hers, and it was to that, she would have thought to which she owed allegiance. But Isabella wondered whether she would ever owe allegiance to any but herself.

If this were so, she was following the teachings of her father. She had learned not so much through what he had said to her as by watching his actions.

She had lived through stirring years in the history of her country. She knew that her father had always tried to curb the power of Rome and how it infuriated him to realize that to many of his subjects the Pope stood above him and that they believed they owed first allegiance to the Church rather than to the State.

There had been a bitter quarrel with Pope Boniface who had dared say that if the King of France did not mend his ways he would be chastised and treated as a little boy. With this admonition had come the threat of excommunication and this was something all dreaded. A weaker man might have sought to placate, but Philip looked for revenge. He demanded that his subjects support him against the Church and so did they fear his ruthless revenge if they did not that most were ready to obey him. The rich Templars were one community which refused to do so.

Vindictive as he was, Philip vowed he would not forget this and although he never scrupled to break a promise if he saw an advantage in doing so, a vow such as this was he was determined to carry out.

He was a strong man, her father. Only fools would go against him. Even the Church should have considered before acting rashly. She admired him so much.

She was proud to be his daughter.

Philip had sent Guillaume de Nogaret, his trusted minister, to conspire with the Pope’s enemies against him. This he did so successfully that they captured Boniface in the town of Anagni and held him prisoner. He was rescued but that incident had impaired his health and his reason and he died soon after. A new pope was elected who was sponsored by the King of France. This was Benedict.

Isabella had glowed with pride at her father’s success. Men were right when they said that he was the most powerful man in the world Even the Popes must obey him. But the Pope was far away and Benedict must have forgotten his promises to the King of France which he had given in exchange for his support at the time of his election, for very soon he was talking of excommunicating any who had brought harm to his predecessor Boniface and wanted the matter of his imprisonment inquired into.

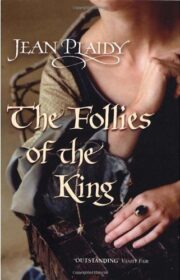

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.