‘My love,’ said Mortimer, ‘this is a cruel blow, but let us plan carefully. It is your son who will decide to whom he will listen. Let them give him his barons and bishops. You are still his mother.’

She held out her hand and he kissed it. ‘How you always comfort me, Mortimer,’ she said.

‘It is my purpose in life, my dearest.’

‘Yes, we shall defeat them,’ she said. ‘You and I will not be set aside for these men.’

‘Assuredly we shall not.’

They sat down on one of the window-seats and he put an arm about her.

‘How beautiful you looked this day in your regal ermine,’ he said soothingly. ‘A Queen in very truth.’

‘But not good enough to be their Regent,’ she said bitterly.

‘Isabella, my love. We shall outwit them all. Do not forget. We have young Edward.’

She nodded but she was not completely at ease. She had begun to have doubts about Edward.

She was right in thinking that the young Edward was becoming apprehensive. He was beginning to understand more of what was going on around him. He could not be proud of his parents and he now knew why people had constantly compared him with his grandfather.

His father had been weak and dissolute, favouring handsome young men and frittering away the kingdom’s wealth in extravagant gifts for them. His mother was living in open adultery with Roger de Mortimer, and they made no attempt to hide it.

He often thought of that brief period when they had stayed at Hainault and he and Philippa had talked together. He had told her a great deal about his perplexities and, although she had been very sheltered from the world and did not understand half those problems which beset him, she had shown him a wonderful sympathy, an adulation almost which had been very sweet to him.

He had told her that he was going to marry her. It was fortunate that there had been some arrangement between his mother and her parents that he should marry her or one of her sisters.

‘Rest assured, Philippa,’ he had vowed, ‘it shall be you.’

She had believed him. Although he was but a few months older than she was and they were only in their fifteenth year there was a resolution about him which she trusted would bring him what he wanted. To her Edward was like a god, strong, handsome, determined to do what was right. She had never met anyone like him, she had said; and he had replied that she felt thus because they were intended for each other.

Strange events were happening all around him. His father was a prisoner. It was wrong surely that a King should be made the prisoner of his subjects. But it was not exactly his subjects who had made him a prisoner. It was his wife, the Queen.

He had been fond of his father as he had been of his mother, for he had always been kind to him, had shown him affection and been proud of him. His mother, though, had charmed him. When she had taken him to France he had begun to feel uneasy because of the trouble about his father. Hainault had been a brief respite because Philippa was there. But since their return to England events had moved fast. There had actually been war between his father and mother and his mother was notorious. The Despensers had been brutally done to death and his father was a prisoner. Wliat would they do to him?

A cold feeling of horror came over him.

‘I like it not,’ he said aloud, ‘and by nature of who I am, I am in the centre of this.’

When his mother came to him with the Archbishop of Canterbury and his uncies the Earls of Kent and Norfolk he was ready for them.

They knelt before him; there was a new respect in their manner; he believed that something had happened to his father.

The Archbishop spoke first. ‘My lord,’ he said, ‘the King your father, showing himself unworthy to wear the crown―’

Edward caught his breath. ‘My father is―dead?’

‘Nay, my lord. He lives, a prisoner in Kenilworth. There he is well cared for by the Earl of Lancaster. But because he has shown himself unworthy to govern he is to be deposed. You are the new King of England.’

‘But how is that possible when my father lives? He has been crowned the King of this country.’

‘The crown is too burdensome for his frail head,’ went on the Archbishop.

‘You are to be the King. You must have no fear. You are young and will have a Regency to show you how to govern.’

‘I have no fear for myself,’ said the young Edward. ‘But I have for my father. I would see him.’

‘That, my lord, cannot be,’ the Archbishop told him.

The Queen said: ‘It would only distress him, Edward. It is kinder to let him be where he is. I hear that he is contented enough. More, he is happy to be relieved of the duties of kingship which have been too much for him.’

‘Yet he ruled for many years,’ said Edward.

‘And see to what state the country has come!’ replied the Queen. ‘Edward, you must remember you are young. For a little while you must listen to advice.’

‘It is well that you should be crowned with as little delay as possible,’ added the Archbishop.

Edward looked into their faces. He felt the blood rising to his. ‘I would agree on one condition,’ he said.

‘Condition, Edward!’ cried the Queen. ‘Do you realize what honour is being done to you?’

‘I realize fully what this means, my lady,’ replied Edward firmly, ‘but I will not be crowned King of this realm until I have my father’s word that he gives me the crown.’

There was consternation. The boy had shown firmness of purpose which they had not expected. He stood straight, drawing himself to his full height which was considerable even though he had not yet finished growing; his blue eyes were alight with purpose, the wintry light shone on his flaxen hair. It might have been his grandfather who stood there.

Every one of them knew that it would be useless to attempt to coerce him.

He was going to do what he believed to be right.

They saw that they would have to get the old King’s permission to crown the new one before they could do so.

The January winds were buffeting the walls of Kenilworth Castle. Outside the frost glittered on the bare branches of the trees. It was a break prospect but not so bleak as the feelings of the King as he sat huddled in his chamber in Caesar’s Tower in a vain endeavour to keep warm.

He had heard the ciatter of arrivals in the courtyard below. He wondered what this meant. Every time someone called at the castle he feared the arrival might concern him and even these miserable conditions be changed for worse.

This was an important visit.

Lancaster stood in the doorway. ‘Your presence is required below, my lord.’

‘Who is it, cousin?’

‘A deputation. They are in serious mood. The Bishop of Hereford leads them.’

‘Adam of Orlton,’ cried the King. ‘This bodes me no good then. He was always my enemy. Who comes with him?’

‘Among others Sir William Trussell.’

‘Ay, an assembly of my enemies, I see. Tell me, do the greatest of them all come to Kenilworth to see me?’

Lancaster was silent and the King went on. ‘You wonder who I mean?

Come, cousin. You know full well. I mean the Queen and Mortimer.’

‘They are not here, my lord.’

‘Why do these men come, cousin? You know.’

‘They have not told me their business, my iord. Come, dress now. They are waiting.’

‘And the King must not keep his enemies waiting,’ retorted Edward bitterly.

‘Give me my robe, cousin.’

He threw off the fur in which he had wrapped himselfand put on a gown of cheap black serge— the sort poor men wore in mourning, for he was mourning he knew for a lost crown.

He faced the party— the traitors who no longer showed him the homage due to a King. Leading them were two of his most bitter enemies Adam of Orlton and William Trussell. How he hated Trussell, who had sentenced Hugh to the terrible death which had been so barbarously carried out!

Trussell’s eyes— like those of Adam of Orlton— were gleaming with triumph. This was a moment for which they had been working in their devious ways for many years.

They did not bow to him. They regarded him as they might a low-born criminal.

Then Adam began speaking; he listed the crimes of the King. Events long forgotten were recalled and the blame for them laid at his door. Bannockburn― Would they never forget Bannockburn? How many had been blamed for that!

He lowered his eyes. He did not want to look into those vicious faces. He wondered what they planned to do with him. Not what they had done to Hugh― beioved Hugh. They could not. They dared not. He was still their King.

Their faces seemed to recede and he thought Gaveston was beside him― Gaveston― perhaps the best boved of them all. Gaveston Lancaster had caught him in his arms. He heard his voice from a long way off. ‘The King has fainted.’

He was coming back to reality. The same chamber― the same faces about him. So it could only have been for a moment.

They brought a chair for him. He was so tired. He did not want to listen to them.

Vaguely he gathered that they were telling him that he was to be set aside, his crown taken from him, and that they wanted his consent to do so.

How kind of them, he thought. They wanted his consent! Why? Could they not do with him what they liked? Cut off his head― Take him out and do to him what they did to Hugh― No, he could not bear to think of what they did to Hugh. It haunted his nightmares. Hugh― beautiful Hugh.

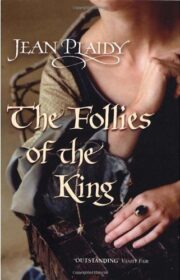

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.