They sounded uncommonly like that much sought after pair, the King and his favourite. Bearing in mind what had happened to the latter’s father— and the whole country was aware of that— no one wanted very much to do with these matters. Careless dabbling could bring a man to the terrible fate of that new law against traitors which made honest men shudder in their beds to contemplate.

It was not long before Lancaster’s men arrived at the farm.

‘We are betrayed,’ said Hugh. ‘My lord, this will be the end.’

The King was treated with respect. Not so Hugh. He was roughly seized by men who delighted in heaping indignity upon him.

‘Come, pretty boy,’ they said. ‘It will be rather different for you now.’

They dragged him away from the protesting King. ‘Where are they taking him?’ demanded Edward.

‘To his Maker I’d take wager, my lord,’ was the answer. Edward covered his face with his hands. He wanted to shut out the sight of Hugh’s appealing eyes as he was dragged out of his sight.

He was courteously treated. He was to go to the castle of Llantrissaint, he was told.

‘On whose orders?’ he asked.

They did not answer.

‘You forget that I am your King,’ he said.

And they were ominously silent.

But he was not really interested in his own fate. He could only think of what they had done to Hugh’s father. Oh, if they should do that to Hugh, he would die of despair.

So they were parted at last. Their attempts to escape had come to nothing, as they might have known they would.

And he was to go to bleak Llantrissaint Castle, the prisoner of someone— his wife, he supposed. Mortimer?

Meanwhile Hugh le Despenser was on his way to Bristol to be delivered to the Queen.

Hugh stood before them. They were seated on chairs like thrones— the powerful beautiful Queen who had once made a show of humility and had been so careful to hide her hatred from him, and Mortimer, strong, bold, virile, as different from Edward as a man could be. It was said that the Queen was besottedly enamoured of him and their association was now of some duration.

Looking back Hugh could see that it had been inevitable from the moment they had met. They were a match for each other— passionate ambitious people. The Queen was as ruthless as her father who had destroyed the Templars.

What did she plan for Edward? He trembled to think. That it would be diabolical, he did not doubt. Her father had brought on himself the curse of the Templars. Perhaps she would bring retribution on herself too.

And young Edward? Where was he?

If I could but see young Edward, he thought, there might be a chance. I could move him to pity for his father’s plight.

‘So here is Hugh le Despenser,’ said the Queen. ‘You look less happy, my lord, than when I saw you last.’

‘That was a long time ago, my lady.’

‘Indeed it was. Why then you were like a petted dog. You sat on your master’s satin cushion and were well fed with sweetmeats.’

‘There will be no more sweetmeats for Hugh le Despenser,’ put in Mortimer grimly.

‘I do not expect them,’ replied Hugh with dignity.

‘Well, you gorged yourself while they were led to you,’ laughed the Queen.

‘Oh, it is going to be very different for you now, you know.’

‘So I had thought.’

‘We are going to London,’ said the Queen. ‘We are going to receive the homage of my good and faithful people. Alas for you, I fancy they do not like you very much.’

For a moment he thought of good honest Walter Stapledon and wondered what his last hour had been like in the hands of the London mob.

‘I must accept my fate for all come to that.’

‘He relinquishes his life of luxury much more easily than I had thought he would,’ commented the Queen.

‘Oh he has much to learn yet,’ responded Mortimer grimly.

Hugh was praying silently: Oh God give me strength to meet what is coming to me.

‘Take him away,’ said the Queen.

They left Bristol for London. Isabella rode at the head of her army with Mortimer on one side and Sir John of Hainault on the other. Adam of Orlton was with them. He was determined to have a say in affairs.

Among the Queen’s baggage was the head of Walter Stapledon. Mortimer had suggested it be placed on London Bridge but the Queen was too wily for that.

‘No,’ she had said, ‘he was a churchman and many would say he had been a good man. He was our enemy and he never pretended to be otherwise. Such men have a habit of becoming martyrs and I fear martyrs more than soldiers. Nay. I shall show my virtue by sending it to Exeter and having it buried in his own cathedral. It will be remembered in my favour.’

‘You are right, my love,’ replied Mortimer. ‘But are you not always right?’

She smiled at him lovingly. She wished as she had so many times that Mortimer had been the son of the King and she had come here to marry him instead of the unworthy Edward.

Hugh le Despenser rode with them. It had been their delight to find an old nag for him to ride on. He and the King had always cared so passionately for horses and they had once possessed some of the finest in the kingdom. This poor mangy animal called further attention to his degradation and in case any should fail to be aware of it as they entered the town through which the processions passed Isabella and Mortimer had commanded that there should be trumpets to announce the arrival of Hugh le Despenser and attention be called to him as he ambled along on his wretched nag.

Hugh felt sick with despair. He knew that a fate similar to that given his father was awaiting him and he knew there was no way of avoiding it. He fervently hoped that he would be able to meet his death with courage.

He had eaten nothing since he had been taken. He was growing thin and ill with anxiety more than from lack of nourishment.

Isabella watched him with apprehension.

‘He looks near death,’ she said. ‘Are we going to be cheated of our revenge?’

‘He could be,’ agreed Mortimer. ‘Indeed he looks near to it. I’d say there was a man who was courting death.’

‘He need not go to such lengths. He does not need to court death.’

‘We should not wait to reach London. I doubt he will outlast the journey.

We should stop at Hereford, and try him there. It would be safer.’

‘Alas, I wanted to give my faithful Londoners a treat. How they would have enjoyed the spectacle of pretty Hugh on the scaffold.’

‘I’d say it was Hereford or just quiet death.’

‘Then it must be Hereford,’ said the Queen.

They had reached Hereford and there they halted for the trial of Hugh le Despenser.

His guards told him that the day of his judgment was at hand.

‘Little did you think when you sported with the King that it would bring you to this,’ taunted one of them.

He was silent. He felt too tired to talk. Besides there was nothing to say.

He was taken to the hall where his judges were waiting for him. They were headed by Sir William Trussell, a man who could be relied on to show him no favour. Trussell had fought against the King at Boroughbridge and when Lancaster had been overthrown he had fled to the Continent. He had returned to England with Isabella and had become one of her firm adherents.

He now harangued Hugh, listing the crimes of which he was accused. He had mismanaged the affairs of the kingdom in order to gain money and possessions; he had been responsible for the execution of that saint Thomas of Lancaster and had attempted to hide the fact that miracles were performed at his tomb. His inefficiency had been the cause of the defeat of Bannockburn. In fact any ill which had befallen England since the death of Gaveston and the rule of the Despensers had been because of Hugh’s wickedness.

Of course there was no hope for him.

‘Hugh, all good people of this realm by common consent agree that you are a thief and shall be hanged and that you are a traitor and shall therefore be drawn and quartered. You have been outlawed by the King and by common consent and you returned to the court without warrant and for this you shall be beheaded; and for that you made discord between the King and Queen and others in this realm you shall be disembowelled and your bowels burned; so go to your judgment, attained wicked traitor.’

Hugh listened to this terrible sentence almost listlessly. It was no surprise. It had happened to his father. It was their revenge and he had known from the moment they had taken him that it was coming.

All he could do was pray for courage, that he might endure what was coming to him with fortitude.

There was to be no delay, ordered the Queen. Delay was dangerous. He might die and defeat them of their satisfaction. Almost immediately after the sentence had been passed, he was dressed in a long black robe with his escutcheon upside down. They had said he should be crowned because he had ruled the King so they placed a crown of nettles on his brow to add a little more discomfort and he was dragged out of the castle.

As they prepared to hang him on the gallows which was fifty feet high in order that as many as possible might witness the spectacle, the Queen took a seat with Mortimer and Adam of Orlton on either side of her that they might gloat over the pain inflicted on the King’s favourite.

The handsome body now emaciated beyond recognition dangled on the rope and Isabella feared that he might die before they could cut him down and administer the rest of the dreadful sentence.

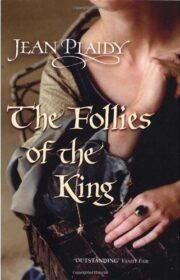

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.