He was one of those who was half in love with her.

‘It is good,’ said Mortimer, ‘to have the King’s brother with us.’

Others like the Earl of Richmond and Henry de Beaumont were in constant attendance. All useful adherents, all enemies of the Despensers who had offended them too often.

So the plan progressed well.

But of course she must appear to be doing the task which she had come out to do.

At length Charles agreed that he would send no more troops into Gascony and would consider returning the conquered provinces to England if Edward came and paid long overdue homage to him for his French possessions.

She had many opportunities of talking to Mortimer because he formed part of that little court which surrounded her and if she could talk in private with her cousin Artois and the Bishops of Norwich and Winchester so could she with Mortimer.

‘What if he comes?’ she asked.

‘The Despensers will persuade him against it.’

‘He and they are eager for peace.’

‘Yes, but they are not going to let him come without them and would they be welcome at your brother’s court? There is an alternative.’

‘I know,’ she said. They looked at each other and marvelled at the manner in which they even thought alike.

‘Do you think he would allow it?’ asked Mortimer. ‘He is fool enough to.’

‘If we had the boy here, we should be half way to victory.’

‘We can try it,’ said the Queen.

‘With the utmost care. Let him think you but do it to ease him and because you think it is time the boy began to realize his obligations.’

‘I will do it,’ said Isabella. ‘But first I must get my brother to agree.’

‘First,’ said Mortimer, ‘let us wait and see what Edward’s answer is. We must by no means seem over-eager for the boy to come in his place. We have to tread very warily, my dear love.’

‘How well I know it,’ replied Isabella.

When the Despensers heard the terms the King of France had set, they were, as Isabella and Mortimer had guessed they would be, very disturbed.

The matter had been before the Council and there it was agreed that Edward should go to Paris. The Despensers were worried. They discussed the matter earnestly together and came to the conclusion that the King must on no account be allowed to go.

‘Without his protection,’ said the elder to the younger, ‘there would be some excuse to seize us. Then I would not give a penny for our chances.’

‘Edward would never allow them to harm us.’

‘My dear son, they would not wait for Edward. Look how they treated Gaveston and even Lancaster was hurried to his death. Once they had us, depend upon it, we should be dead men before Edward could do anything to save us.’

‘To go is the only way he can save his French possessions.’

‘To stay is the only way he can save us. No, Hugh my son, the King must not go to France. You must persuade him against it. He must remain here.

Without him, with the country in the mood it is in, we are lost.’

‘Is it really as bad as you think, Father?’

‘My dear son, you are constantly with the King. You divert him. You are his greatest friend. I have time to look around at what is happening. I happen to know that Henry of Lancaster has been writing to that Adam of Orlton who I am sure had a hand in Mortimer’s escape from the Tower. He had put up a cross to his brother’s memory at Leicester and is circulating more stories about more miracles at Lancaster’s tomb. No, Edward must not go. You must seek means of detaining him. Do not let him give a direct answer.’

Edward was only too ready to be detained. He had no fancy for going to Charles of France and doing homage. It was an act never relished by any of his predecessors.

He was delighted when the communication came from Isabella.

She had spoken with the King of France and he had agreed that if Edward found it difficult to leave his realm at this time he would accept the homage from young Edward. She believed that it was an excellent notion and if the King agreed to send their son it would be a good exercise in diplomacy for the boy and she would take good care of him.

If he agreed, young Edward could be created Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Ponthieu and could then pay homage to her brother Charles for these provinces.

Edward was delighted. The Despensers discussed the matter together. It would keep Edward in England and their lives could depend on that.

‘Let the boy go,’ said Hugh to the King. ‘It will be a good experience for him. He is growing up. It is time he began to take part in affairs. He can lessen your burden, my lord. Yes, let the boy go.’

Edward’s life had been one long series of mistakes, but in sending his son to France he made the greatest mistake of them all.

Isabella and Mortimer could scarcely believe their good fortune. Their plan was progressing beyond their wildest hope.

With what joy she rode to the coast to wait the coming of the Prince!

Mortimer was beside her.

‘Soon,’ he whispered, ‘we shall be going home. We shall go at the head of an army. Nothing could have served us better than the coming of young Edward.

The fact that the King sends him shows that he is unworthy to rule. It is now our task to see that the boy is on our side.’

‘Fear not that I can win him to us,’ replied the Queen.

‘None could withstand your charm,’ Mortimer assured her, ‘least of all a young boy― and he your son.’

It was a wonderful moment when young Edward stepped ashore. He was such a handsome boy, showing promise of Plantagenet good looks. He was going to be tall as his father and grandfather had been; he was flaxen-haired with keen blue eyes, alert, intelligent, eager for life, aware of his destiny and determined to fullil it.

He was accompanied by the Bishops of Oxford and Exeter and a train of knights. All these, thought the Queen, must be won to our cause.

The boy was clearly overwhelmed by his mother. He would have bowed to her but she would have no ceremony.

‘My son,’ she cried. ‘My dearest son, it makes me so happy to see you. So handsome, so healthy. Oh my dear boy, I am so proud of you!’

Young Edward coloured faintly. He had always admired his mother; she was so beautiful and she had always made it clear that he was the favourite of her children. He had heard it said how patient she was in enduring her humiliations.

He was beginning to understand his father’s way of life and deplored it. He knew that there was trouble in the country because of it and that one day he would be the King. When that time came it would be different. He would make sure of that. He had heard a great deal about his grandfather and he wanted to be like him.

Walter Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, had talked to him of his duty and had impressed on him that his life must be dedicated to the service of his country. So he was delighted to be with his mother and to ride beside her to Paris. He was not sure how he should feel towards Mortimer. He knew that the Earl had been his father’s prisoner and had escaped from the Tower. But his mother seemed very friendly with him and Mortimer certainly made a great effort to please the young Prince. And even his uncle, the King of France, showed affection for him and told him bow glad he was that his father had agreed that he should come.

On a September day in the Castle of Bois de Vincennes near Paris young Edward paid homage to Charles IV of France in place of his father. It was an impressive ceremony and enacted with a show of amity, but the French King was too wily to stick entirely to his bargain. He might restore Gascony and Ponthieu but he had suffered considerable losses in the action, he complained, and for this reason, he thought it was only fair that he should keep the Agenais.

Isabella and Mortimer looked on with pleasure at the ceremony. The trouble was that now the homage had been paid and the King of France satisfied, there was no longer any reason why the English party should remain in France.

To leave would mean saying good-bye to Mortimer. Moreover if she went back to England Isabella would be in the same position as she had been before.

Of course she must not return and the task now was to gather as many people as possible to their banner, and when they had a considerable army, then would be the time to strike.

There already existed a nucleus of discontented people from England and this grew daily. But it was not an army. Isabella wondered whether her brother would help, but Charles was disenchanted with war and he had no intention of carrying on one in England.

He had offered hospitality to Mortimer because he thought he could supply useful information about England; moreover Mortimer was a declared enemy of Edward so therefore it was wise to have him at hand. Naturally he received his sister who was also Queen of England but he did not expect even her to outstay her welcome.

Mortimer and Isabella realized that although the first part of the mission was accomplished, they had had incredible luck. But now they had to conjure up an army from somewhere. How?

It was true the cause was growing. Many of the people who formed part of their circle could raise men back in England.

The situation grew more and more difficult every day. Even the King was beginning to wonder why the English party did not make preparations to leave.

Isabella and Mortimer had anxious meetings together. They would not be separated. Moreover it would be very dangerous for her to leave now. There were surely spies at court and it might well be that someone had noticed the relationship between them and had reported it to Edward.

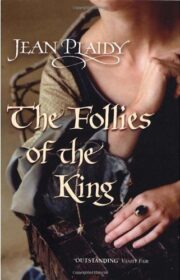

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.