He felt like a conqueror.

Isabella was delighted. He had acted for her and for the first time had shown he had some regard for her. She received him warmly in London. It was good that the Badlesmere woman had not been hanged but had been brought to the Tower. Had she been hanged they could have made a martyr of her.

‘You must take advantage of your success,’ she told him. ‘Look you, Edward, the whole of London is on your side. The barons will see this and perhaps not be quite so eager to stand against you.’

She was right. Several of the barons who had been dismayed that the Queen should have been denied access to her own castle now came to the King with their followers to show him that they had had enough of Lancaster’s vacillating.

‘Now is the time to break Lancaster’s power,’ said the Queen.

They were together, she and Edward, as they had never been before, but if he thought she would forget past insults at the turn of fortune he was mistaken.

The victory at Leeds had been an easy one— an army against one woman defending a castle— and the Queen was working towards a goal which did not include the King. But she would make use of him now; and as Lancaster had proved to be no real friend to her― although in the beginning it had seemed that he might be― she was ready to eliminate him.

‘You know Lancaster is a traitor,’ she said to the King.

‘I have had ample evidence of that,’ replied Edward. ‘He has been against me constantly.’

‘And have you wondered why in their raids the Scots never touched his lands?’

‘I know there are rumours that he has an understanding with Robert the Bruce.’

‘An understanding with Robert the Bruce! When he is your subject!’

She said: ‘We must if we can, lay hands on the letters which have passed between Bruce and Lancaster and if we do― oh if we do― then who can deny that we have a traitor in our midst?’

Edward’s mood had changed. He was all set for success now. He marched up to the Welsh border and the Mortimers’ land.

The Mortimers immediately sent word to Lancaster that the King’s army was on the march. They should join together and then they could defeat him.

Edward was not famous for his prowess in battle and with the might of their two armies they would be invincible.

Lancaster’s reply was that this would be so but he failed to send his army, and without him the Mortimers were not strong enough to face those thousands of the King’s supporters who now that they had a more resolute Edward at their head (since his victory at Leeds), were ready to their hearts into the fight.

The result of the encounter was the débâcle of the Marcher men and much to Edward’s surprise he found that two of his most formidable enemies were his prisoners— Roger de Mortimer, Lord of Chirk, and his nephew, Roger de Mortimer, Lord of Wigmore.

They were immediately sent to the Tower.

It was success such as Edward had never dared dream of. He knew now how his father had felt throughout his long fighting life.

THE END OF LANCASTER

HE now turned his attention to Lancaster.

Letters had been found. It was true that Lancaster had been in communication with the King of Scotland and in the letters he had sent to Bruce he had signed himself King Arthur. That was ominous and Isabella was right.

He must destroy Lancaster. There could be no peace for him until that was done.

With this object in view he planned to march north.

It was now clear that Lancaster was taking a firm stand against the King. He did indeed parley with the Scots whose great desire was to see a civil war in England. Sir Andrew Harclay, who was the warden of Carlisle, was aware of this and came in great haste to Edward to inform him of what was happening.

Edward sent him back to Carlisle with instructions to attack the English traitors and inform him at once if they were joined by the Scots.

Action took place at a long bridge which crossed the River Ure. This bridge was very long but narrow and at its approaches, the Lancastrians came face to face with Sir Andrew Harclay and his force which was drawn from the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland. These man had very good reason to hate the Scots and their allies; and that the latter should be English incensed them.

Humphrey de Bohun, Lord Hereford, attempted to take the bridge on foot, while Lancaster tried to cross the river on horseback and attack Harclay’s men from the flank. Lancaster however found Harclay too strong for him and he suffered great losses. Meanwhile de Bohun while on the bridge was killed by a spear being run through a gap in the planks of the bridge from below and entering his body.

The Battle of Boroughbridge had ended in the annihilation of Lancaster’s forces and his own capture.

At Pontefract Edward was waiting to receive his cousin.

Lancaster faced him with a lack of animation. He knew that the long battle between them was over. He despised Edward and wondered what the future held for him. He shrugged his shoulders. Whatever it was it would have no consequence for him.

He did not attempt to remind the King of their relationship; he would not plead for his life.

It was over. He had enjoyed power but he had not possessed the talents to keep it.

‘Your trial will take place at once,’ said the King. Lancaster bowed his head and was led from the King’s presence.

The trial was quick and Lancaster was found guilty of conspiring with the Scots against the King. He had used the soubriquet of King Arthur in his dealing with Robert the Bruce. King Arthur! the court tittered. It was clear that Lancaster had had a high opinion of himself and where his ambitions lay.

Papers had been found addressed to Bruce containing a suggestion that he come into England with a good army and Lancaster would see that a good peace was made.

Edward sat watching his cousin, and he was thinking: You killed Perrot. You boasted of it. Yes, you were proud of it. And when he thought of that beautiful body being destroyed he almost wept. But this was revenge. This would be the end of Lancaster.

He could almost hear Perrot laughing beside him. Dear Perrot, he should be avenged.

Edward listened to the words of the prosecutor.

‘Wherefore our Sovereign Lord the King having duly weighed the great enormities and offences of the said Thomas, Earl of Lancaster and his notorious ingratitude has no manner of reason to show mercy―’

He was to die the traitor’s death, that horrible one, which had now become the custom— hanging, cutting down alive and burning the entrails after which the body was cut into quarters and distributed for display.

But in the case of noblemen the sentence was diverted to death by beheading, and as Lancaster was royal this should be done to him.

They put him on a grey pony, and thus he rode through the town where the people came out to jeer at him and throw at him anything they considered disgusting enough. Stones cut his face and he turned neither to right nor left and it was as though he was completely unaware of the blood which ran down his face.

‘King Arthur,’ cried the mob, ‘where are your knights, eh? Why don’t they come and rescue you? Let them take you back to your round table.’

He looked straight ahead. Gaveston had suffered a similar fate to this ten years before. Was this why they were taking him to the hill? Was this why they made him ride on the little pony, why they sought to rob him of his dignity?

All men must die at some time, but it was sad that a royal earl should come to it this way. Then suddenly the enormity of what was happening to him seemed too strong for him.

‘King of Heaven,’ he murmured, ‘grant me mercy for the King of Earth has forsaken me.’

They reached St Thomas’s Hill outside the city of Pontefract. He saw the block. He was aware of the watching faces avid for blood, eager to see the ignoble end of one who had not long before been the most powerful man in the land.

He turned his face to the east.

Someone cried: ‘Turn to the north, man. That’s where your friends are.’

He was roughly pushed. Now he was looking ahead to where beyond the border was the land of the Scots.

He knelt and placed his head on the rudely constructed block.

The axe descended and Lancaster was no more.

Warenne brought the news to Lancaster’s wife.

Alice de Lacy looked at him with disbelief.

‘‘Tis so,’ said Warenne. ‘He was found guilty of plotting with the Scots and that has been his undoing. He was sentenced to the traitor’s death but because of his noble birth he was not hanged drawn and quartered but taken to St Thomas’s Hill near Pontefract where they cut off his head.’

‘Pontefract,’ she murmured. ‘It was his favourite spot.’

‘Well, it is over, Alice. What now?’

‘I am free,’ she said. ‘It is what I and Ebuio have longed for. But I wish it could have come about in a different way. Poor Thomas, he was so proud― and clever in a way, but he did not understand how to treat people. It has been his downfall.’

‘There is no longer the need for you to remain in hiding.’

‘I have so much to thank you for.’

‘Lancaster was my enemy, you know. It was my pleasure to disconcert him.’

‘I think you had a certain kindness in your heart for a woman placed as I was.’

‘It could be so,’ he answered. ‘And now?’

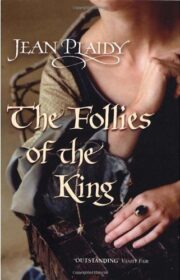

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.