Trouble in the north broke out and this meant that all attention was focused on the border. Edward marched north with Lancaster to besiege Berwick.

Isabella and her ladies were left behind in Brotherton, a village near York. She was growing impatient. She was advancing well into her twenties; she had three children, born as she often thought, in humiliation. She, reckoned to be the most beautiful princess in Europe at one time, and none could deny she was still a handsome woman, was a notoriously neglected wife. She would never ever forgive Edward for the humiliation he had made her suffer. The people of England loved her— but it was partly because they were sorry for her. Well, one day she was going to make use of that sympathy. She was going to show Edward that she had always despised him, and that she had borne her children out of expediency. Her nature had revolted. She could not deeply love those children, because they were Edward’s too and conceived in necessity. But she was devoted to her first-born, which might have been due to the fact that all her hopes rested on him. She visualized the day when he might stand with her against his father. During her stay in Woodstock she had thought of herself as resembling Eleanor of Aquitaine whose sons had stood with her against their father.

There was a commotion below. Men were riding into the courtyard. Starting to her feet she went down to see what was happening and was startled to find men she recognized as the servants of the Archbishop of York.

‘Something has happened,’ she cried.

‘My lady,’ said the spokesman of the men who she saw were troops, ‘the Archbishop has sent us with all speed. He begs you to prepare to leave without delay. The Black Douglas is at hand with ten-thousand of his men and it seems that his plan is to take you hostage.’

Hostage to Black Douglas! A great soldier and patriot with a complexion so dark that it had earned him his name. Her eyes sparkled at the thought of adventure. At least she thought Black Douglas was a man.

‘Is this indeed so,’ she said. ‘And how has this come to your knowledge?’

‘My lady, if you will prepare to leave at once you shall hear all when you are safe.’

She hesitated.

‘There is a force of loyal troops surrounding the castle,’ said the spokesman.

‘You must leave at once or you will be in acute danger. The Scots are uncouth.

They might not know how to treat a Queen.’

In less than an hour she was riding away from the castle in the company of the Archbishop’s men.

It was then that she heard what had happened. One of the Scottish scouts had been discovered in the town and because of his strange accent suspected. He was taken to the Archbishop and asked to explain his business. This he could not do to the Archbishop’s satisfaction and finally on being threatened with torture he had admitted that Black Douglas was marching on York, his plan being to abduct the Queen and hold her prisoner.

When she arrived in York she was greeted by the Archbishop who was delighted to have saved her but at the same time he believed that it would be dangerous for her to stay and that she should leave at once for Nottingham.

The King had expressed little concern for Isabella. She was aware of this and hated him for it. She remembered how distraught he had been when Gaveston had been threatened and how he had once left her behind at Scarborough in his need to escape with his beloved friend. If Hugh le Despenser had been threatened he would have been in a state of panic.

Oh yes, indeed, it was unforgivable.

Edward could not continue the Scottish war. The Scots could not be driven out of Yorkshire. They had a grand leader in Bruce and what the English lacked was just such leadership. Edward was weak; Lancaster was little better. It was a sorry time for England.

Edward had been forced to suggest a two-year truce with Scotland, and rather to his surprise Bruce had agreed. He did not know then that Bruce was becoming alarmed by the state of his health. Years before he had been in contact with lepers and the dreadful disease had begun to show itself. It was alarming and he needed rest from the rigours of a soldier’s life and for this reason he was ready enough to agree.

Edward was jubilant. He was the sort of man who could live happily in the moment and shut his eyes to the disasters threatening the future which to the discerning eye would appear to be inevitable. He was behaving as foolishly over Hugh le Despenser as he had over Gaveston and the lesson of that earlier relationship appeared to have made no impression on him. The Despensers were as greedy as Gaveston had been, as power-hungry and because of this, growing as unpopular with the people.

He will never learn, thought Isabella.

She was pleased that Edward was to go to France to pay homage to the King — Isabella’s brother Philip V— for Ponthieu. It would give her an opportunity of sounding Philip and trying to discover how much help she could get from him if she should need it. She wondered whether it might be possible one day to place herself at the head of those barons who had had enough of the King and the Despensers. She had often thought of it when Gaveston had been alive, but it had not been possible then. At that time she had not been the mother of two fine boys. Young Edward was growing up long-legged and flaxen-haired like his father and his grandfather; he was also showing a certain seriousness which seemed to please everyone.

She had heard it said: ‘That one is going to be Great Edward over again.’

That was what she liked to hear.

Now there was the journey to Amiens. She liked to travel and in her own country she was always greeted with loyal affection. She noticed that the people were less effusive towards Edward. It was natural. News of his neglect of her would have reached the country and the people were offended on her account.

It was pleasant to be at the French Court again. She found it more graceful than that of England. The clothes of the women were more elegant. She was ashamed of her own and determined to have some gowns made to wear in France and take back with her.

Edward did the necessary homage and she had an opportunity of talking alone to her brother.

Poor Philip! He looked far from well. His skin was yellowish and he had aged beyond his years. He had only been on the throne for four years and it seemed as though he were going the same way as Le Hutin.

‘You are much thinner, Philip,’ she told him ‘Have you consulted your doctors?’

Philip shrugged his shoulders. ‘They are determined I am to die shortly. The curse, sister.’

‘I should snap your fingers at them and tell them you refuse to die at the command of Jacques de Molai.’

‘Do not mention that name,’ said Philip quickly. ‘No one does. It is unlucky.’

Isabella shook her head. If she had been in her brother’s place she would have shouted that name from the turrets. She would have called defiance on the Grand Master. She would have let the people of France see that she could curse louder than the dead Templars.

But she was not subject to the curse.

‘Charles is waiting to step into my shoes,’ said Philip ‘That will be years hence and perhaps never.’

Philip shook his head. ‘I think not. And then― his turn will come. Tell me of England, sister.’

‘Need you ask? You know the kind of man I married.’

‘He still ignores you and prefers the couch of his chamberlain to yours?’

‘I would my father had married me to a man.’

‘He married you to England, sister. You are a Queen, remember.’

‘A Queen― who is of no importance! I hate these Despensers.’

‘The two of them?’

“Father and son. He dotes on them both but it is of course the pretty young man who is his pet.’

‘Well, sister, you have a fine boy.’

She nodded and whispered: ‘Yes, brother. I rejoice. Two boys and young Edward growing more like his grandfather every day. People comment on this.’

‘What England needs now is another First Edward.’

‘What England does not need is the Second Edward.’

‘But that is what it has, Isabella.’

‘Perhaps not always. Perhaps not for much longer.’

He was startled. ‘What mean you?’

‘There is whispering against him. The barons hate the Despensers as much as I do. If it should come to― conflict―’

She saw her brother’s face harden and she thought: How wrong I was to expect help from him. All he is concerned with is his miserable curse.

‘It would be wise for you to continue to please him.’

‘Continue! I never began to.’

‘Oh come, sister, you have three children by him.’

‘Begotten in shame.’

‘You should not talk so. They are his and yours.’

‘They are indeed. But what I have to endure―’

‘Princes and princesses must always accept their fates, sister.’

What was the use of trying to get help from Philip?

But there was one other who was brought to her notice during that visit to France. This was Adam of Orlton, Bishop of Hereford, who conveyed to her that he had great admiration for her fortitude regarding her relationship with the King.

It was not long before they were finding opportunities of talking together.

He deplored the state of the country and the troubles between the barons. He hinted that he thought the Despensers were responsible for a great deal of the people’s growing dissatisfaction.

‘My lady,’ he said, ‘It is the affair of Piers Gaveston over again.’

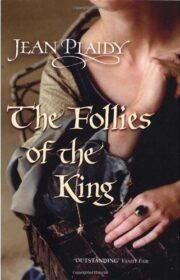

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.