Edward agreed with her. He had talked over the matter with Hugh who had actually seen the man.

‘He is handsome enough,’ was Hugh’s comment. ‘Tall and fair. And he certainly has a look of the late King and yourself. But what a difference! The poor creature has no grace, no charm. He is an uncouth yokel.’

‘What do you expect him to be?’ demanded Isabella tartly, ‘brought up by a tanner! I doubt you, my lord, would be as charming and graceful if you had been brought up in a hovel instead of the ancestral home of the Despensers.’

Hugh tittered sycophantically. They were beginning to hate each other. In due course, thought Hugh, he would not have to placate her. It would be the other way round.

The Queen said: ‘I do believe this man should not be treated lightly.’

Edward looked at Hugh. Oh God, prayed Isabella, let me keep my temper.

This is going to be darling Perrot all over again.

Hugh was not completely sure of his position, so he said quickly: ‘There is much in what you say, my lady.’

‘Poor fellow,’ said Edward, ‘I doubt he means any harm.’

‘He is only helping to make you more unpopular than you already are.’

Edward said petulantly: ‘The people are so tiresome. Am I to blame for the weather?’

‘They won’t blame you for the weather,’ said the Queen, ‘but for doing nothing to combat the effects of it. They don’t realize that Lancaster rules them now― not their King.’

She was not going to argue with them. If the King liked to be lenient with this man, let him. His folly was leading him to disaster fast enough.

She left the two friends together. Now they would put their pretty heads together and talk of the past. Hugh must be sick to death of hearing of the talents and virtues of Darling Perrot.

But John of Powderham was not allowed to go free. He was arrested and imprisoned. He was given a chance to bring forward proof which might substantiate his claims to be the son of the King.

Of course, the poor fellow could do nothing of the sort. But he insisted on his claim. He knew it had happened the way he had said. What more proof did they want than the character of the present King.

He had given his accusers the opportunity they needed.

Poor John Powderham was sentenced to that horror which had become known as the traitor’s death. He was hung, drawn and quartered.

An example to any of those who might have notions that Edward the Second was not the true King of England.

There were further signs of unrest.

Soon after the affair of John Drydas, a certain Robert Messager was in a tavern having drunk a little more than his wont when he remarked that it was small wonder things went wrong with the country when the manner of the King’s way of living was considered.

There was quiet in the tavern while he went on to speak very frankly of the King’s relations with Gaveston and now it seemed there was a new pretty boy favourite. It was a wonder the Queen— God bless her― endured the situation.

Many in the tavern agreed and the more Robert de Messager drank, the more frankly he discussed the King’s friends.

There was bound to be someone who reported this conversation and the next night when Messager was in the tavern there was a man there also who plied him with wine and led the conversation to the habits of the King.

Messager, seeing himself the centre of the company and that he had the interest of all, used what were later called ‘irreverent and indecent words’ about the King.

As he uttered them, the stranger made a sign and guards entered the tavern.

Shortly afterwards Messager found himself a prisoner in a dark little dungeon in the Tower. Realizing what he had done he became quickly sober when he was seized by despair and a realization that his own folly had brought him there.

There was a great deal of talk throughout the capital about Robert de Messager. He was a citizen of London and London looked after its citizens.

Messager had spoken of the King in a London tavern. He had merely said what everyone knew to be true. Perhaps he had been indiscreet. Perhaps he owed the King a small fine. But if he were to be condemned to the traitor’s death there would be trouble.

The Queen as usual was aware of the people’s feelings. When she rode out they cheered her wildly. It seemed that the more they despised Edward, the more they cherished her. They saw her as the long-suffering Princess who had tried to be a good wife and Queen to their dissolute monarch.

‘Long live Queen Isabella!’

Then she heard a voice in the crowd: ‘Save Messager, lady.’

Save Messager! She would. She would show the people of London that she loved them as they loved her.

She looked in the direction from which the voice had come. There was a shout again: ‘Save Messager.’

She replied in a clear voice, ‘I will do all I can to save him.’

More cheers. Sweetest music in her ears. One day everything would be different.

She had some influence with Edward. He did respect her. The fact that she never upbraided him for his life with Perrot and Hugh won his gratitude. She had given him the children― two boys. What could be better? They must have more, she had said. Two were not enough. He really owed her a good deal for being so considerate. She was prepared to receive him that they might have children, and she loved their two boys— even as he did. There was a bond between them and he was ready to listen to her.

‘You must pardon Messager,’ she said.

‘Do you know what he said about me?’ asked Edward.

She did know. She did not add that Messager had spoken the truth.

‘Nevertheless,’ she said, ‘I want you to pardon him. The people have asked me to intercede for him and I think it well for them to believe you have some regard for me.’

‘But they know I have. Have you not borne two of my children?’

‘The Londoners wish him to be pardoned and they have asked me to do what I can. They want him pardoned, Edward.’

‘But to speak of his King thus―’

‘Edward, it is better for you to waive that aside. The people will gossip less if you do. It is not often I ask you for anything. But now I ask you for this man’s life.’

Edward rarely felt fully at ease with his wife, and the prospect of her begging for this favour and that it should be for the life of a man appealed to his sense of the romantic.

Let the man go. Show the people that he cared not for their calumnies and make a pretty gesture to his Queen.

When Robert de Messager was released the crowds gathered to cheer him.

He had struck a blow for freedom. He had come near to horrible death and thank God— and the Queen— that he had escaped.

‘God save the Queen,’ shouted the people of London. She rode out among them.

‘How beautiful she is!’ cried the people.

‘Shame on the King,’ said some. ‘Such a good and lovely Queen and he turns to his boys!’

And she smiled and acknowledged their loyal greetings. They loved her.

They were on her side. One day she would have need of them.

Another unfortunate incident occurred soon after that.

It was Whitsuntide and the Court was at Westminster and the celebrations took place in public according to the custom.

At such times the doors of the palace were wide open and it was the people’s privilege to come in if they wanted to see the royal family at table.

At such a time as this, with famine throughout the country, it was asking for trouble to allow the poor to see how well stocked the royal table was. There had, it was true, been certain shortages in the kitchens, even of the most wealthy, but to the poor the joints of beef and the golden piecrust looked very inviting.

The King and Queen sat side by side at the great table and the King was beginning to realize that if the Queen was beside him― as a queen should be— the people were more inclined to look with favour on him.

However, while they sat at table there was a commotion from without and then suddenly there appeared at the door a tall woman on a magnificent horse.

The woman’s face was completely covered by a mask so that it was impossible to see who she was.

She rode into the hall and brought her horse right up to the table where the King was seated. Then she handed a letter to him.

Edward was smiling, so was the Queen.

‘A charming gesture from one of my loyal subjects,’ said Edward. ‘I wonder what the letter contains?’

He gave it to one of his squires and commanded that it be read aloud so that the whole company could hear.

He was expecting some panegyric such as monarchs were accustomed to receiving on such occasions when, to his amazement, this squire began to read out a list of complaints against the King and the manner in which the country was ruled.

‘Bring back that woman,’ he said, for the masked rider was already at the door.

She was captured and immediately gave the name of the knight who had paid her to deliver the letter to the King.

The knight was brought before the King who demanded to know how he dared behave in such a manner.

The knight fell on his knees. ‘I wish to warn you, my lord. I am as good and loyal a subject as you ever had. But the people are murmuring against you and I believe you should know it. I meant the letter to have been read by you in private. I was ready to risk my life to tell you.’

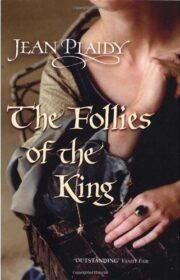

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.