The Queen was in his dreams, her beautiful face a mask of resignation concealing her true emotions. Odd that he should think of that now.

We should have paid more attention to the Queen. That thought kept going round and round in his head. It was absurd. What could a woman do? Women perhaps were more dangerous than some men because they acted in a more mysterious manner. Hatred was obvious in the dark eyes of Joseph the Jew and Lancaster’s scheming face and the foaming lips of Mad Dog Warwick. But how could he know what schemes were planned behind the beautiful face of Isabella the Fair?

He was awakened from an uneasy dream. There were noises below. He heard the shouts of the guards and then silence. He started up but before he could rise the door was opened and figures from his dream were at his bedside.

Warwick, the Mad Dog, was looking down at him.

‘So, my fine fellow, we have you, eh?’ he said.

Gaveston looked up at that cruel dark face, noticed the spittle about the thin lips and said with an attempt at his usual cynicism: ‘So the Mad Hound of Arden has come to Deddington Rectory.’

‘Aye!’ cried Warwick. ‘He is here. He is taking you where you belong.

Beware lest he take you by the throat and kill you.’

‘You cannot touch me. I have the word of the Earl of Pembroke. I am to have a free trial and I am to see the King.’

‘Since when has the Earl of Pembroke given orders to Warwick? Get up. Or we will take you as you are― naked. The dungeons of Warwick are not made for comfort. Be wise and dress warmly. If you can do it quickly, you may still have time.’

‘I protest―’

‘Take him as he is then,’ cried Warwick. ‘The pretty boy likes us to see himself as nature made him. He fancies he is prettier that way than in the finest garments. It may be, Gaveston, but we are not of a nature to admire. Get up. Or I will call my guards.’

Gaveston reached for his clothes and under the eyes of Warwick, hastily dressed.

About his neck he wore a chain set with jewels and there were several rings on his fingers. They were all he had brought with him from Scarborough.

Warwick noticed them. ‘The chain was a gift from the French King to our King,’ he said. ‘The rings are royal too, are they not? How you love jewels, pretty boy. Crown jewels preferred. You stole them from the Treasury.’

‘I did not. I did not. The King gave me― everything―’

‘Ah, he did so. His honour, his people’s regard and mayhap his kingdom.

Guards. Take him.’

‘You will have to answer to the Earl of Pembroke. He had given me his word.’

‘Leave the Earl of Pembroke to me. You should be concerned with yourself.’

As he stepped out into the night air, he knew where they were going and a terrible despair filled his heart.

When Pembroke arrived at the rectory to prepare to continue his journey he was horrified to hear that Warwick taken his prisoner away.

‘This is unpardonable,’ he cried. ‘I have given my word for Gaveston’s safe conduct. This is a slight on my honour.’

He was in a quandary, for he had sworn to the King that no harm should befall Gaveston and he had pledged his lands on this.

Little could have been more dangerous for Gaveston to fall into the hands of Warwick; and Pembroke knew that if anything happened to the favourite the King would be so mad with grief and that he would insist on Pembroke’s being stripped of his lands.

He appealed to Warwick who laughed at him and declared that Gaveston was his prisoner and was remaining so. Lancaster, Hereford and Arundel were on their way to Warwick where they would decide Gaveston’s fate.

Frantically Pembroke sought out the young Earl of Gloucester, for the King’s sister, Joanna, was his mother. Gloucester had been neutral in the affair of Gaveston: Margaret was Gaveston’s wife. Poor Margaret, wife to such a man was an empty title and she had long ceased to admire him, which at the time of her marriage, when she was very young, she had done because he was so pretty.

But when she had learned of his true nature, her feelings had changed. Yet at the same time Gaveston had become a member of the family and families usually clung together, though Glouchester had not come out in Gaveston’s favour because the favourite had offended him on one occasion by calling him Whoreson— a derogatory reference to his mother, the Princess Joanna, who had married old Gloucester and almost immediately after his death had turned to Ralph de Monthermer and secretly married him.

Gaveston had been very sure of himself in those days. He was a reckless fool, like a gorgeous dragonfly revelling in the sun of royal favour, never pausing to consider that the baronial clouds could rise and cover it.

Gloucester shrugged aside Pembroke’s suggestion that they should band together and storm Warwick Castle to rescue the favorite.

‘You cannot expect me to go to war for Gaveston!’ he cried, aghast.

‘The King would be on our side.’

‘The King― against Warwick, Lancaster, Arundel and God knows how many more! Do you want to plunge this war for the sake of that man?’

‘I gave my word.’

‘Then you should have taken more pains to make sure you kept it.’

‘It seemed safe enough. He was well guarded. Warwick came by night with an overpowering force.’

‘You never should have left him. You should have taken him to the castle with you.’

‘I know that now. But at the time it seemed safe.’

Gloucester shrugged his shoulders.

‘I have pledged my lands to the King for his safety,’ pleaded Pembroke. ‘I shall lose everything.’

‘Then mayhap this will teach you to be a better trader next time.’

‘But he was promised safe conduct.’

Gloucester turned away. He could not shut out the sight of Gaveston’s face, the eyes glittering, the mouth slightly lifted at one comer. ‘That Whoreson Gloucester―’

Gaveston would now pay for the fury he had aroused in the hearts of powerful men.

It was their turn now.

Lancaster, Hereford and Arundel had arrived at Warwick Castle.

‘So you have him here,’ said Lancaster.

‘He is in one of the dungeons. He has lost his bombast. He is now full of fear as to what we have planned for him.’

‘So should he be,’ replied Lancaster grimly.

‘What shall we do with him?’ asked Warwick, ‘He must not be allowed to live,’ Lancaster pointed out. ‘Every day he is alive could mean danger. What if the King mustered an army and came to take him? What would our position be then?’

‘We should be fighting against the crown,’ put in Warwick. ‘Civil war.

There was enough of that under John and Henry.’

‘There is one thing to be done,’ said Lancaster. ‘We must pronounce sentence and carry it ont. The man is a traitor. He has stolen the crown jewels. A fortune was left behind at Scarborough. He is under excommunication. He deserves death and at a trial he would be found guilty. My lord, there is one thing we must do. We must carry out the sentence before there is more trouble.’

‘He deserves the traitor’s death.’

‘Hanged, drawn and quartered. Yes, but how? Moreover, he is connected by marriage with Gloucester’s sister which gives him a link with royalty. It is enough that he loses his head.’

‘Who will strike the blow?’ asked Hereford looking from Warwick to Lancaster.

Arundel said: ‘The man who does that places himself in danger.’

‘It is no time to think of that,’ retorted Lancaster sharply. ‘The blow must be struck. He must lose his head.’

‘When?’ asked Arundel.

‘This night.’

‘So soon?’

‘Who knows what tomorrow could bring?’ cried Lancaster. ‘What if the King arrived to take him from us?’

‘There will be no peace in this land while he lives,’ said Warwick. ‘The people will rise against the King if Gaveston goes back to him. They like not this relationship between them. They want him to be with his Queen. They want another man such as his father was― a family man who will give the country heirs.’

‘Great Edward the First gave us our present King. He was great in all things save one— the giving of an heir.’

‘Hush my lord. That’s treason.’

‘Treason― among friends. We know it is all true.’

‘That may be. But let us rid the country of Gaveston and see what comes then.’

‘He must go.’

They all agreed to that. And who should actually strike the blow? That man would be the enemy of the King forever.

They came to a decision. It should be an unknown hand that killed Gaveston. The noble earls would merely be spectators and the men who struck the blows should be humble soldiers whose identity would be lost when they mingled with their fellows.

It was the only way.

‘Come, Gaveston.’

It was Warwick who spoke to him.

‘It is time to go.’

‘To go where?’

‘Whither the Mad Hound leads.’

‘You never forget that, do you?’

‘There are some things which are never forgotten.’

‘You harbour more resentment against me for calling you that than for snatching the championships at Wallingford.’

‘Have done. There is little time for such badinage. You should be saying your prayers.’

‘So you are going to kill me?’

‘You are going to meet your deserts.’

‘And my fair trial?’

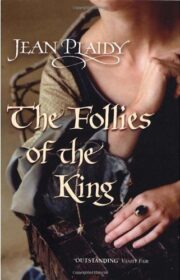

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.