Edward covered his face with his hands. ‘I hate to hear of it, Walter. I will not allow it here.’

‘Under this torture many of the knights have confessed to obscene practices.’

‘What they say under torture does not count.’

‘Indeed it does. The purpose of the torture in to reduce them to such agony that they will do anything to stop it.’

‘I do not want it here, Walter. I do not want it. Why cannot people be merry and gay and laugh and sing together? Why does there have to be this vileness?’

‘Ah, my lord, you are gentle and kind. All kings are not so. Least of all your father-in-law. He acts with demonical fury against the Templars. He wants their money and he wants an excuse for taking it. Doubtless they would be willing to give it to him but that will not suit him. He must ease his conscience. Therefore he must prove to the world and himself that these men deserve to be dispossessed.. This he does through torture when they confess to the sins he and his friends like Philip de Martigny, Archbishop of Sens, and his minister, Guillaume de Nogaret, have thought up for them.’

‘Perhaps they will refuse to confess,’ said Edward. ‘What then?’

‘Then there will be further torture and that such that such as few can withstand. I have heard that many have lost the use of their feet after being submitted to a certain form of treatment which the soles of the feet are greased and set in a screen which is placed before a fire. I have heard that the slow burning is one of the most agonizing tortures devised by men. There are many others―’

‘I do not wish to hear of them,’ cried Edward. ‘Walter, I do not wish that the Templars in England shall be arrested. Perhaps they could be warned. Perhaps they could give up some of their wealth― but I do not wish them to be tortured or burned at the stake, I am sure Perrot would agree with me if he were here.’

‘Ah, Perrot!’ sighed Walter. ‘But what good news of him in Ireland!’

Edward brightened. ‘I am so proud of him. Even Mad Dog Warwick had to admit that the news was good. The way in which he dealt with the rebellion in Munster was magnificent.’

Walter nodded. ‘If he goes on like this, my lord, you might suggest he comes back.’

‘Do you think they would listen?’

‘Who knows? They might be ready to. Let him go on for a while as he has begun and even his worst enemies won’t be able to deny that he has made a good job of Ireland.’

Edward forgot the distress he felt at the treatment of the Templars in contemplation of that glorious possibility.

But when he sat with his council and expressed his views regarding the Templars, he was pleased to find that the majority of his ministers agreed with him.

Each day there was news of the terrible fate that was befalling the Templars in France and of how many were arrested and taken before the council set up by the Archbishop of Sens. Some would not confess to their alleged sins even under the most violent torture and were taken to the stakes which were set up all over Paris and burned to death.

Nothing was too revolting to be laid at their door, and their enemies were hard put to it to think up new crimes committed. Many of them were escaping from France and that did not suit Philip.

He wanted the entire Order wiped out. He demanded that other countries follow his lead; he was most displeased at the attitude of his son-in-law. His greatest advantage came from his puppet the Pope. The Templars must be destroyed, thundered Clement. Excommunication could well be the wages of those who ignored the command.

The threat of excommunication could always arouse alarm. Edward was persuaded by his ministers that although he might defy his father-in-law , he could not defy the Pope. That the Pope was acting on the instructions of the King of France was true, but behind the Pope was the image of the Holy See and the people feared it.

There was a half-hearted attempt in England to suppress the Templars but this could not be allowed to proceed and in a short time the Pope had sent his inquisitors to deal with the matter. It was the first time that the Inquisition had been set up in England; many determined at that time that it should never come to their shores again and by great good fortune, it never did. It brought with it a change in the attitude of people. Fear had come into the land. There had been persecution before of course; there was cruelty; but the sinister inquisitors shrouded in religious fervour with their instruments of torture and their secret administrations had brought something to the country which had never been there before.

The Inquisition did not lack victims. Countless arrests were made. The tales of what happened in those sombre chambers of pain were whispered in dark corners. Insecurity was in the air.

Edward had said that he would have no burnings at the stake and it was ordained that the Templars should be disbanded, their property confiscated and they could find places where they could settle into civil life.

The Templars could not believe their good fortune for they were well aware of what was happening in France. True, they must find new ways of existence but at least they had been left with their lives.

The Inquisition finally departed from England to the great relief of the people.

Never, never, they vowed, should it come to these shores again Meanwhile the horrible tortures persisted in France and the Grand Master himself suffered. He was in his seventies and to the delight of the King of France could not stand up to torture and was ready to confess anything of which he might be accused, but it was not possible for Philip to consign him to the flames. He must receive his sentence of death from the Pope. That would come in due course. Meanwhile Philip concerned himself with lesser men and revelled in their property which was more than even he had dared hope.

Edward had replenished his exchequer also, which gave him much relief, but was glad he had not the sin of murder on his conscience.

His behavior over the matter of the Templars had brought him a certain popularity with the people. In fact, they had always been fond of him and had blamed Gaveston for the troubles in the kingdom. When he rode out with the Queen he was cheered, and seeing them together the people thought that the scandalous affair of the king and Gaveston was over now.

If the Queen could give birth to a son, they would be popular indeed.

In his heart, Edward did not greatly care. All he wanted was the return of Gaveston and he began to plan for his return.

Perrot was clever. He was doing so well in Ireland that even his greatest enemy— Warwick perhaps— had to admit that this was so.

As for Edward, he sought to placate those very men who had dismissed Perrot, and they were not unwilling to be placated. He was after all the King and the King’s friendship must mean a good deal to them all. Edward was realizing more and more that there was only one thing he desired— that was the return of Gaveston, and he was ready to do anything to bring it about.

His friendship with Walter Reynolds had always been a source of irritation to the nobility who deplored the King’s partiality for those of humble birth. He had recently made Walter Bishop of Worcester and had actually attended the consecration by Archbishop Winchelsey at Canterbury. That was a great mark of favour. Walter was well known as a crony of the King and Gaveston; he was standing with Edward now against the barons and was believed to be working for the return of Gaveston. So it was clever of Edward to send him off on a papal mission to the Court of Avignon where he would have to remain for some time. That was not all. There was one man whom Gaveston’s enemies were very eager to see removed from his position near the King. This was Hugh le Despenser. He had been dismissed from the council at the time of Gaveston’s banishment but he still remained close to the King.

The departure of Walter Reynolds had so pleased the barons that Edward had another idea which he confided to Hugh.

‘My dear friend,’ he said, ‘you know my regard for you. You must never think that it has faltered. I am a faithful friend I trust, to those who serve me well.’

‘Your fidelity to the Earl of Cornwall can never have been surpassed,’ said Hugh.

‘Ah Perrot! How I miss him. But he will come back to us, Hugh. I am determined on it.’

‘I pray so night and day, my lord.’

‘I know you are our good friend, Hugh. That is why you will understand what I am going to do. I must have Perrot back. I shall die if he does not come to me soon. I have sent Walter to France. Did you see the effect of that? They could not believe it and they took it as a sign that I have reformed my ways and am going to be the sort of King they want me to be.’

‘I have noticed it, my lord. Walter was desolate to go and you to lose him.’

‘He understands, as you must, Hugh. I am going to dismiss you.’

Hugh’s face was blank. He was so eager not to show his emotions.

‘It will seem that you no longer please me as a close friend, but that is untrue. You must understand that. I shall be seen everywhere with Isabella.

Please understand what this means to me. I must have Perrot back.’

‘I understand well, my lord. You will win the barons and the Queen to your side and then you will say that there is no reason why the Earl of Cornwall should not come back. He has proved himself an able lieutenant and good servant of the country; and you must have grown out of your infatuation with him for you are dismissing your old friends and becoming a good husband to the Queen.’

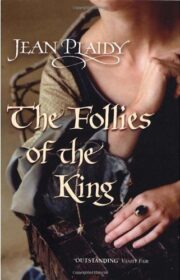

"The Follies of the King" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Follies of the King". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Follies of the King" друзьям в соцсетях.