That was as good as a confession of guilt, and his lordship called his clerk and had it written out fair. Young Matthew, blind and numb with grief, put his name to it, perhaps thinking to end this miserable interrogation so that he could go home and grieve for her in peace.

But they did not let him go. The clerk had two constables with him and they bundled him into their own carriage, a horrid affair with no windows and no door-handles on the inside. They took him to Chichester gaol and they threw him in with the self-confessed murderers and rapists to await sentencing at the quarter sessions.

And Richard rode home under a sickle moon humming the tune Matthew had sung with the others when we had brought the spring to Wideacre only the day before.

I was still asleep and I did not wake until the next morning when a great shout from downstairs woke me. It sounded like Ralph’s voice, but I could not believe that Ralph could have raised his voice in my mama’s house. I glanced at the window. It was late, nearly ten o’clock. Mama must have given orders that they should leave me asleep. For a moment I could not think why, and then my heart sank as I remembered that Clary was dead, killed by a stranger, and that there had been a murderer in the woods of Wideacre, that my wrist was broken in a fall from my horse and that I had somehow lost my courage – perhaps for horse-riding, perhaps for life – and that I could not stop a little tremor in my hands. I could not stop myself from weeping.

I stretched out for my wrapper at the foot of my bed and gave a little gasp of pain. I moved more cautiously then and dragged it on over my shoulders. I opened my bedroom door and listened. It was Ralph’s voice and he was shouting in the library.

‘An Acre lass dead, an Acre lad in Chichester gaol for her murder and a worthless confession to hang him! My oath, Dr MacAndrew, you have been damned remiss in this!’

Uncle John’s voice was soft; I could not make out the words.

‘Why was Julia not there, then?’ Ralph demanded. ‘If you did not summon me, why was it not done before Julia? She is part heir to Wideacre, equal to Master Richard. Why was Master Richard alone so busy in the matter?’

Ralph was silent while Uncle John answered, but I still could not hear what he said.

‘If Miss Julia was half dead with typhus fever, she should still have been there!’ Ralph bellowed. ‘This news has gone like wildfire around the village and everyone is angry, knowing a mistake has been made. Something like this could wreck the accord between the village and you. Acre has trusted you, and now there is an Acre lad behind bars with a hanging crime over his head.’

‘He made a confession.’ John’s voice was clear now, louder.

‘Aye,’ Ralph said with sarcasm. ‘And who was there? Lord Havering, who comes to the county in the shooting season and when he is short of funds. And Master Richard!’

‘What exactly are you saying, Mr Megson?’ Uncle John demanded, his tone as icy as Ralph’s was hot.

‘I’m saying that Acre does not trust the ability of Lord Havering to tell a horse from a haystack,’ Ralph said rudely. ‘We think he is half blind and half drunk. And I am saying that I do not trust Richard farther than I can pitch him. Why he should want poor Matthew Merry to hang, God alone knows, but everyone in Acre believes that Richard has sent that lad to gaol and will send him to the gallows.’

There was absolute silence in the library. I held my breath to listen.

‘I take it you will accept a month’s wages in lieu of notice, Mr Megson?’ asked Uncle John coldly.

‘I will,’ said Ralph, and only I could have heard the despair in his voice.

‘No,’ I said, and I ran across the landing to my mama’s room. She was sitting before her mirror, her hair down, with Jenny Hodgett frozen behind her, brush upraised. Mama looked around as I came into the room and nodded at the mute appeal in my face. She tossed the lovely unbound hair carelessly over her shoulders and went past me, downstairs. We went in together. I scarcely glanced at Ralph Megson. I was trembling again and praying inwardly that Mama would take control. I was as much use as a new-born kitten. I could feel the tears under my eyelids. Uncle John was sitting at the table, writing out a draft on his bank account.

‘Mr Megson must stay,’ Mama said. Uncle John looked up and noticed her morning dress and her hair tumbling down her back. His eyes were very pale and cold.

‘He has accused your step-papa of drunkenness and incompetence, and he has accused Richard of perjury,’ Uncle John said blankly. ‘I assume that he would not wish to work for us any more.’

I glanced at Ralph. His face was impassive.

‘Mr Megson,’ my mama said softly. ‘You will withdraw what you have said, won’t you? You will stay? There are so many things in Acre yet to be done. And you promised Acre you would help to do them.’

His eyes met hers for a long measuring moment, and then he nodded.

He was about to say yes.

I know he was about to say yes.

But I had left the library door open behind me; the front door opened and Richard came in and checked as he saw us. He took in the scene and he beamed at Ralph as if he were delighted to see him.

? problem?’ he asked.

‘Mr Megson thinks that Matthew Merry is innocent,’ John said abruptly. ‘Are you sure you put no pressure on him, Richard? It is a hanging matter, as I am sure you realize.’

Richard’s smile was as candid as a child’s. Of course not,’ he said. ‘Lord Havering was there all the time, and his clerk too. It was all completely legal. It was all conducted with perfect propriety.’

Ralph puffed out with a little hissing noise at Richard’s mannered enunciation of ‘perfect propriety’. I saw my hands were shaking and I clasped them together to keep them still.

‘And have you no doubt at all?’ Uncle John demanded. ‘Matthew is a young man, ill-educated, and he was taken by surprise. Are you certain he knew what he was signing? Are you positive he knew what he was saying?’

‘That is really a question for the examining Justice,’ Richard said easily. ‘You should ask Lord Havering, sir. It was his examination and deposition. I was just there because I reported the crime to him and told him that I thought there was a case against Matthew Merry if he chose to examine it. I had no other role to play in the matter.’

I said nothing. I was watching Ralph. His eyes were narrowed and he was staring at Richard. ‘You’re your mother’s child, all right,’ he said. Uncle John looked at him, and they exchanged a hard level gaze.

‘I’d like to stay if I can,’ Ralph said abruptly. ‘May I have a day to think it over, and also to go into Chichester to see what can be done for Matthew?’

Uncle John nodded. ‘I should like you to stay if we can agree, Mr Megson,’ he said. ‘We’ll leave the decision for a day and a night, if you please. We were both heated and I should hate to lose you because of hasty words of mine said in anger.’

Ralph’s shoulders slumped, and he gave John one of his slow honest smiles, ‘You’re a good man,’ he said, surprisingly. ‘I wish we were all clear of this coil.’ One swift hard look at Richard made it clear that he blamed Richard for all that had come about.

I looked from one to the other and I could not tell where my loyalty should lie.

Ralph nodded again. ‘There’ll be no work done today,’ he said, businesslike. ‘The carpenter is making her coffin and they’re digging her grave. She’ll be buried this afternoon at two o’clock, if you wish to attend. Tomorrow they’ll go back to work. They don’t want to keep the maying feast with the prettiest girl in the village dead and the sweetest lad in the village under wrongful arrest. It has all gone wrong for Acre this year.’

Uncle John said, ‘Yes’ softly, his head down. That last sentence seemed to toil in my head like the echo of a church bell which sounds on and on long after the ringers have stood still. It seemed I had heard it before. Then I saw John’s stricken face and guessed that someone had said it to Beatrice when she wrecked Acre, and that he was afraid that the Laceys were wrecking Acre again.

Ralph swung out of the room without another word and we heard his wooden legs clump across the polished floor of the hali I went weakly into the chair by the fireplace and sank down, my head in my hands, the tears spilling over, helpless.

My mama went to John. ‘Don’t look so desperate,’ she said. ‘It will all come right. We cannot help poor Clary, but you and I can go to Chichester, as well as Mr Megson. If Matthew denies his guilt today, now he has had time to think, then perhaps Richard and Lord Havering may find they were mistaken. Certainly the quarter sessions are not for months yet, so there is plenty of time to set things right if a mistake has been made.’

Uncle John’s head come up at that and suddenly I could see how aged and tired he looked. ‘Yes,’ he said. Then, more strongly, ‘Yes, Celia, you are right. Nothing is beyond our control. Events have moved very swiftly, but no final decision has been made. We can perfectly well see Matthew in prison, and if he tells a different story, then we can resolve the problem.’

We all looked towards Richard. One might have thought that he would fire up at this challenge to his judgement, but he was smiling and his eyes were the clearest of blues. ‘Of course,’ he said, ‘whatever you wish.’

Something in his voice made me put my head in my hands and weep and weep.

Mama and John never spoke to Matthew. As they were getting in the carriage to go to Chichester to see him, a message came over from Havering Hall. The prison authorities had sent to Lord Havering to tell him that his prisoner, Matthew Merry, had been found hanged in his cell that morning. He had hanged himself with his belt. They had cut him down as they brought him slops in the morning, but he was already cold.

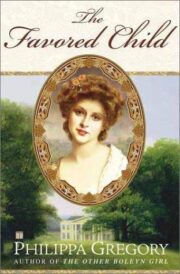

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.