I nodded. Prince was walking on the soft turf in the centre of the drive. Even that smooth walk jolted my broken wrist and my clenched stomach almost more than I could bear. But the Dower House was in sight, and I gritted my teeth and kept silent.

The front-garden gate was open, and Jem rode Prince right up the path to the door and shouted, ‘Holloa!’ through the open doorway.

I could see a figure coming out from the front hall, and I could feel myself longing for my mama’s safe touch.

But it was not my mama. It was Richard. My mama was behind him, but it was Richard who was first out down the steps and who reached up to lift me down from the horse, and who carried me in his arms like a little child come safe home to him.

‘Julia! Thank God!’ he said. ‘I’ll take her, Jem. There. Gently with that hand.’

Then Mama was at his side and her cheek was cool against mine. ‘Poor darling!’ she said gently. ‘Did you fall?’

I opened my mouth; Richard’s arms around me tightened slightly, imperceptibly. I glanced up at his familiar face, so close to mine. Richard, who had been my dearest love since my earliest childhood. His eyes were shining, he was smiling at me with such warmth, but a little hint of devilry lay at the back of his blue eyes.

‘Tell your mama, Julia,’ he said, and his voice was warm with laughter. ‘Tell us what happened and how you came to hurt your hand like this.’

It was impossible.

I could no more have told her the truth than I could have shouted obscenities at her. I would have been too shamed. Shamed for her, shamed for Richard and shamed for me.

My throat tightened and the tears poured down my face. ‘I fell,’ I said. My throat was still sore and my voice was croaky. ‘I fell from Misty and she ran off.’

Richard turned at once and took me towards the house, Mama holding my sound hand in hers as we went up the stairs to my room. Richard put me gently on the little bed and turned for the door. He paused in the doorway and looked at me, his face alight with amusement, and he closed one eye in a wink as if we shared a most delightful secret. Then he was gone.

I slept until early afternoon when I woke to the noise of my bedroom door opening, and Mama came in with a tray in both hands and her eyes on the level of the milk in the jug.

‘Tea,’ she said. ‘Tea for the invalid. Julia, my darling, I cannot tell you what a fright you gave us all!’

I tried to smile. But I had no smile. And when I sat up in bed, I found my lips were trembling so that I could scarcely speak.

‘My wrist hurts,’ I said childishly.

Mama looked at it. ‘Good gracious,’ she said. ‘It looks badly bruised, or even broken.’ She put down the tray and went straight away out of the room. I heard her footsteps running down the stairs and then I heard her and John come back up together.

He looked at my hand, half clenched against the pain, blue as an iris. ‘Broken,’ he said across me to my mama. ‘You’d best go out, Celia – this is something Julia and I will be better doing alone.’

My mama looked to me. ‘Shall I stay?’ she asked.

‘No,’ I said, though I was past caring.

‘I’ll get my bag,’ Uncle John said.

Setting the broken bone in my wrist was a painful business. Brutish. But in some odd way I welcomed the pain. It was clear, forceful. It was one of the few things left in the world which I could be sure of. The pain of a broken wrist. The small square of Wideacre sky seen from my window. And Richard’s sly, naughty smile.

‘You’ll stay abed for dinner,’ Mama said, looking at my white face when John allowed her back in the room.

‘Yes,’ I said feebly.

‘Would you like anything now?’ she asked.

I drew a breath. I knew I had to tell her. Of course she had to know. ‘Mama…’ I started.

‘Richard said he would have his dinner up here with you,’ Mama offered. ‘I expect you would like the company, wouldn’t you, darling?’

I hesitated. The birdsong outside seemed to go quiet with me.

I could not say it. I could not tell her what he had done to me. I could not tell her how I had lain back and smiled and let it happen. I could not tell them that John’s son and the part heir to Wideacre was a rapist.

‘Yes,’ I whispered. ‘Richard can have his dinner up here.’

‘Good,’ Mama said, businesslike. ‘He’s out in the stables now, seeing to your horse.’

Something broke in my head at that – through the haze of laudanum and the heaviness of my sin. I sat up in bed, and I spoke across Uncle John to my mama. ‘No!’ I said. ‘Mama, please! Please don’t let him touch Misty.’

She shot a bewildered look at John as if this might be some symptom of a blow on the head or high temperature.

‘Please!’ I said urgently. ‘Promise me, Mama! Don’t let him touch my horse.’

‘No, my darling,’ she said gently. ‘Not if you do not wish it. I will go down to the stables now and tell him to come away from her, and leave her to Jem if that is what you wish.’

‘It is,’ I said, and sank back on the pillows.

‘Now sleep,’ John said authoritatively. ‘Sleep until dinnertime. There will be no more pain and there is nothing to worry you, so sleep, Julia.’

I smiled towards him, but I could barely see his face; the room was wavering before my eyes. I think I was asleep before the two of them had left the room.

I slept until dinner.

Richard came upstairs and Jenny Hodgett served our meal and stood discreetly at Richard’s elbow throughout.

I ate little, for I was not hungry. And every now and then I would look at Richard and feel my eyes fill with useless, inexplicable tears. I felt that it was my fault. My fault that it had happened. My fault that I had not told at once, the minute I was home, that through my cowardice Richard and Mama, Uncle John and I would all be living a lie. I had not told when I should have told. And now I could say nothing. I could not even stop Richard smiling at me in that familiar, conspiratorial way.

When Jenny brought up a dish of tea for me, she had a message from Uncle John: if ‘I felt well enough, Mr Megson was downstairs and would speak with me. Richard left the room and Jenny helped me from my bed and into my wrapper. I knew it must be something important for Ralph to come to the house at this time of night, and I paused before my mirror to push my hair back and tie it with a ribbon. I knew that I would not be able to tell Ralph either. I wondered if he would know without being told that I had lost my honesty, that I was a liar.

Ralph and Uncle John were downstairs in the library. He smiled at me and asked after my accident, and apologized for calling me downstairs when I was unwell. I nodded. Ralph and I had always been mercifully brief with each other.

‘Clary Dench is missing,’ he said shortly. ‘I’m trying to discover when she was last seen and if she had plans to go away for the holiday.’

I took a deep breath. I could scarcely understand what he was saying. ‘I saw her on the downs, at the maying,’ I said. ‘She said she was going home, and she left early. She was planning no holiday away from Acre.’

Ralph nodded. ‘I can’t believe she’d go off without a word to anyone,’ he said, half to Uncle John, half to me.

‘D’you think some harm has befallen the girl?’ Uncle John demanded.

Ralph grimaced and glanced at me in case I could help him. ‘It’s always hard to tell with wenches,’ he said. ‘I’ll not turn out the village to hunt for her on a fool’s errand. It’s their first holiday in years and they’ve been out once today already looking for Miss Julia.’

‘Clary’s not flighty,’ I said. The words I was speaking were echoing coldly as if I were speaking down a well. I knew I had seen true on the downs in the morning. I had tried to keep Clary with me then. I had been afraid to tell her how dark a shadow I saw on her. I seemed to be afraid to tell the truth to anyone. ‘She’d have told someone if she was going off. And I don’t believe she’d have left her family without a word like that.’

Ralph nodded. The door opened and Richard came in quietly and stood at one end of the long table, at the carver chair, where the head of the household would sit.

‘What would you wish?’ Ralph asked the air midway between Uncle John and me. He did not even glance at Richard.

‘Take two or three men and look around the woods for her,’ Uncle John said, his eyes on me.

I nodded. ‘Start at the Fenny,’ I said. ‘Clary always went down to the river when she was sad. And she was very sad today.’

Ralph nodded. ‘She had quarrelled with Matthew?’

‘Yes,’ I said, taciturn.

‘I’ll have a few out to look for her,’ he said. ‘But it’s a nuisance. I had promised Acre they would have a couple of days free of work. Now I shall have to order some men out when they will want to be dancing.’

‘I’ll help,’ Richard said suddenly. We all turned and looked at him. He was very bright. ‘I’ll help. There’s little I can do to help on the land,’ he said pleasantly. ‘I’d be glad to save you some trouble, Mr Megson, and help with finding Clary.’

‘Thank ’ee,’ Ralph said slowly. He was looking at Richard very hard, no smile in his eyes. ‘That would be a help. I’ll send the men down to you tomorrow morn, as soon as it is light, unless the lass turns up home before then.’

‘I’ll be ready,’ Richard promised.

Ralph turned to me. ‘And you, Miss Julia? Will you be resting tomorrow or will you be well enough then to come down and at least watch the dancing?’

I was about to say that I would be well enough to go down to Acre tomorrow, but a pang in my belly made me gasp and my eyes filled with ineffectual tears. ‘I’m tired,’ I said weakly. ‘I’ll come down to the village when I feel better, Mr Megson.’

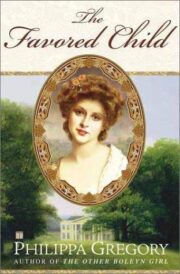

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.