The touch of his tongue in my mouth was like ice.

My eyes flew open, I jerked my head away.

It was Richard.

At once I struggled to be up and away from him, but he did not let me up. His weight, which I had welcomed, was suddenly a weapon. He was pinning me down, and I was not able to struggle against him to throw him off.

‘Richard!’ I said in anger. ‘Let me up! Let me up this minute!’

He said nothing in answer, he would not even meet my eyes. Instead he reached down and fumbled with my skirts and petticoats, ignoring my ineffectual pushes against his chest.

I gasped. Richard had pulled my skirt up to my waist. I had a sudden recollection of the goshawk bating away in a frenzy of terror. I struggled to get my left hand free and I slapped his face as hard as I could.

He shook his head like a bullock stung by a horse-fly and grabbed for that hand. His weight pinned my other arm between his body and mine. I wriggled, but I was helpless.

‘Richard!’ I said more loudly, sharply. There was a hard note of panic in my voice. I heard it, and Richard heard it too. He looked at me then for the first time. His eyes were blank, a glazed blue, bright as glass, expressionless. Then he pushed one hard knee between my legs and parted them, bruising the flesh.

I screamed.

I screamed without thinking if there could be anyone in earshot. I screamed out of terror, without thought of managing Richard or of dealing with him. I screamed in the same mindless fright as that of the goshawk who had launched herself blindly into the air, forgetting she was held fast.

At once, as if my scream were a signal, he twisted the wrist he was holding so tightly that the skin burned with pain and, though I opened my mouth to scream again, all I could do was gasp in horror as I heard the slight click of a small bone breaking, and felt my whole arm, my whole body, burn with pain. Richard dropped my hand and put his palm over my mouth instead.

‘If you struggle, I shall break the other wrist,’ he said softly, almost conversationally. ‘If you scream, I will strangle you. I will strangle you until you lose consciousness, Julia, and then I will do what I have to do, and then I may tighten my hands a little more. Do you understand?’

His face was so close to mine. I could feel his breath on my cheek. He was not panting, he was breathing evenly, steadily; he might have been taking a gentle stroll.

‘Richard…’ I said in a frightened whisper, ‘don’t do this, Richard, please. Why are you doing this?’

His smile was darker and his eyes more navy blue than I had ever seen them. ‘You were going to bring in a rival squire,’ he said. His voice was a thread of hatred. ‘You were going to build a bigger house than Wideacre Hall. I read it in his letter. While you slept there, beside my house on my land, you were dreaming of bringing in a rival squire and claiming half of our land.’

I opened my mouth to disagree, my mind scrambling like a trapped animal for some way out.

‘You are my betrothed,’ Richard said. ‘I was a fool to let you leave Wideacre and a fool to try to win you back kindly. Now I am going to claim you for my own.’

His words, and their meaning, sank in.

‘Richard, no!’ I said. I could feel my throat tightening with terror. This nightmare in the summer-house was too like the bullying of our childhood. I could feel myself slipping from courage, from the strong abilities of my womanhood, into the panic-stricken victim that I had really been when we were children.

‘It will hurt,’ he said with unconcealed pleasure. ‘I think you will be afraid, Julia.’

‘No!’ I screamed, but my throat had clamped tight and no cry came out. I croaked silently, and Richard guessed that I was now too afraid to make a sound, and his eyes sparkled in utter delight.

He put one hand down and loosened his breeches and pulled them down. Then, with one hand holding my wrist, the other back over my mouth, forcing my head back on the dusty floor, he reared away from me, and with one hating, savage thrust he pushed into me, and my scream of pain was choked on his hard hand and my sobs retched in the depth of my throat.

It was like a nightmare, like the worst of nightmares, and it did not stop. While my hurting body registered the pain, I tried to find some courage from somewhere to say, ‘Well, it is done.’ But it was not done. Richard pushed into the blood and the hurt flesh again and again and again. He seemed to take delight in paining me so badly that I was screaming for help inside my head and hot tears were spilling down my face.

He gave a great shudder at the pinnacle of the very worst of it and then he collapsed and dropped his weight upon me as if I were nothing more to him than a bale of straw.

I lay spreadeagled on the dusty floor, where once I had dreamed of passion, with the tears pouring down my cheeks in a morass of pain and misery. I could feel I was bleeding, I could feel a bruise forming on my thigh where he had knelt upon me; but I could not comprehend the pain inside me.

He rolled off me and then was suddenly alert, looking out of the open doorway. He jumped to his feet, without a word to me, and, hitching his breeches, ran down the steps into the rose garden as if all the fiends of hell were after him. He ran from me as if he had murdered me indeed and he was leaving a sprawled body. I lay still, as he had left me, and I stared at the white roof and at the little hole in the timbers where the blue sky showed through, and I felt a little trickle of blood between my legs.

My belly seemed to have gone into some sort of regular spasms of pain, for every now and then it eased, but then there was a great wave which came over me and made me gasp and bite the back of my uninjured hand so as not to cry out. My broken wrist was throbbing, and I could see it was bruised black and swelling.

I lay on the dusty floor with my pretty cream riding habit pulled up to my waist and my hair tumbled down and spread in the dust, and I knew myself to be so broken and destroyed that it would have been better for me if Richard had completed his threat and strangled me while I lay there.

I don’t know how long it was before I sat up. I did not think, I did not think at all about what had happened, or what I could do. All I could think of was an urgent, passionate need to be home. I wanted to be in my bedroom with the door locked. I wanted to be in my bed with the covers up over my head. I sat up, and then I took hold of the doorjamb and heaved myself to my feet. I staggered, but I did not fall. I seemed to have stopped bleeding. My dress was unmarked. I held tight to the door and took one shallow step at a time into the rose garden.

Misty was gone. I shut my eyes and then opened them again in the hopes that I was mistaken, that she was where I had left her. But she had pulled her reins free and taken herself off home.

I sobbed at that, the first sound I had made since I had said, ‘Richard, no!’ in a voice which would not have halted a mouse. Misty was gone and I could not see how I could ever get home. All I wanted, all I wanted in the whole world, was to be home and asleep.

My head was swimming, and my knees buckled and I collapsed on to the step of the summer-house. I rested my head in the crook of my elbow and let the spring sunshine warm my back. I did not think I would ever feel warm inside again. I stayed like that, quite still, for what seemed like a lifetime of numb misery.

Then I heard, in the woods, voices calling my name, over and over again, and a little silence between the calling while they listened for me. I heard hoofbeats on the drive, and Jem’s voice, harsh with anxiety calling, ‘Miss Julia! Miss Julia!’

‘I’m here!’ I said in a pathetic little voice. ‘Here, Jem! At the summer-house!’ I got to my feet and went down the drive to meet him.

He was riding Prince, and I saw the horse suddenly leap forward when Jem caught sight of me. He was beside me in an instant.

‘Did you take a fall?’ he said. ‘Sea Mist came home with a broken rein and her saddle too loose. I guessed you’d come off her.’

I nodded, too weary to speak and too full of pain and confusion to say the unsayable, to accuse.

And anyway, I felt that it was me who was in the wrong.

‘Could you ride?’ he asked me, ‘or shall I go home and send for the carriage?’

I nodded dumbly towards Prince. ‘I want to go home,’ I said pitifully. Jem lifted me up on to Prince’s back, and then vaulted up behind me. His arms were around me, holding me safe and steady, but for a moment’s madness I was suddenly afraid of him, of Jem, whom I had known all my life and who had come out calling and looking for me.

I bit my bottom lip to keep myself from crying out. I knew I had nothing to fear from Jem.

I had not smiled and walked with him. I had not kissed him before all Acre. And I had not promised that we should be married. All these things I had done with Richard, and then I had lied to him about my plans. I had never told him about the plan to live on Wideacre with James. I had never lied outright indeed; but I had kept silent.

And when he had first kissed me in the summer-house, I had smiled.

And when I had first felt his weight upon me, I had put my arms around his neck and opened my mouth for the taste of his tongue.

‘I’m going to be sick,’ I said abruptly to Jem, and turned my head away from him as I retched over Prince’s shoulder.

Nothing came but a mouthful of bile with the acid taste of fear.

Jem turned Prince’s head for home and took us down the drive at a steady walk. ‘Your ma stayed at home in case you were found, or walked home,’ Jem said gently. ‘Everyone else is out looking. I’ll sound the gong when we get in so they know. And someone will pull the school bell to tell ’em you’re safe found.’

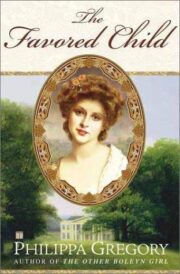

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.