‘When will you learn then, Miss Julia?’ Dench asked me, his brown eyes bright with curiosity. He had seen my face when she fed from my hand, he had seen how she dipped her head for my caress.

‘When Richard has learned,’ I said certainly. I knew Richard would claim the lovely Scheherazade as his own, and I longed to see him ride her. But I knew also that if I did not challenge him and awaited my turn, there would be no one in the world more generous and thoughtful than Richard. We always shared our playthings, and if I was quick to return them and always gave Richard first turn, then we never quarrelled. He would give me unending rides on Scheherazade providing we both knew that she was his horse.

Dench nodded and flung long reins and a bridle over the carriage horse in the stall next door. ‘Master Richard first, eh?’ he said, shooting a look at me. ‘And you don’t mind, Miss Julia?’

‘Oh, no!’ I said, and the smile I gave him was as clear as my thoughts. ‘I want to see Richard ride. I have been looking forward to it for months.’

Dench said something under his breath, perhaps to the horse, and then led her out of the stable and backed her into the shafts of the trap in the carriage-house. Richard and I sat either side of him on the little bench seat and my grandpapa waved his cigar in farewell.

‘See you tomorrow,’ he said jovially. ‘And mind you make your apologies to your mama!’

We did not have to confess. Mama had guessed at once where we had gone and was sitting down to her supper in solitary splendour when the trap came trotting up to the garden gate in the dusk. Before her was a plate of toast and a little jar of potted meat, and she did not look up from buttering her toast when we crept into the dining-room. ‘Your supper is in the kitchen,’ she said, her voice cool. ‘Children who run off like stable lads should eat in the kitchen.’

There was nothing we could say. I curtsied low – a placatory gesture – and backed out of the room in silence. But Richard stepped forward and laid a single red rose, openly thieved from the Havering garden, beside her plate.

Her face softened at once. ‘Oh, Richard!’ she said lovingly. ‘You are so naughty! Now go and eat your suppers and have your baths and go to bed or there will be no riding for you tomorrow, new horse or not!’

And then I let out a sigh of relief for I knew we were forgiven, I could sleep sound in my bed that night, since the two people I loved most dearly in the whole of the unsafe uncertain world were under the same roof as I, and neither of them was angry with me.

‘You shall have a riding habit,’ Mama said softly to me when she kissed me goodnight. ‘I shall find an old gown of my sisters’ at Havering Hall. Or I shall make you a new one.’

‘You shall learn to ride,’ Richard promised me on the stairs as we went up to bed, our candle-flames bobbing in the draughts which came up the stairwell and through the gaps in the bare floorboards. ‘As soon as I have learned, I shall teach you, dear little Julia.’

Oh, thank you,’ I said and turned my face to him for his goodnight kiss. For once, instead of a token buss on the cheek, he kissed me tenderly on the lips.

‘Good Julia,’ he said sweetly, and I knew my refusal of lessons from my grandpapa had been seen and was being rewarded. Plentifully rewarded; for I would rather have had Richard’s love than anything else in the world.

2

Richard’s long-awaited first riding lesson was tedious for my grandfather, humiliating for Richard and two long hours of agony for me. At first I could not understand what was wrong.

When Richard went to mount the horse in the stable yard in the warm end-of-summer sunlight, I saw that his face was so white that the freckles on his nose were as startling as spots in an illness. His eyes were brilliant blue with a sheen on them like polished crystal. I thought he was excited. I thought he was bridle with excitement at the prospect of his first proper ride on a horse of his own.

Scheherazade knew better. She would not stand still when he put his foot to the stirrup, she wheeled in a nervous circle, her hooves sliding on the cobbles. She pulled at the bit while Dench was holding the reins, trying to steady her. She threw up her head and snorted. Richard, one foot up in the stirrup, one foot on the ground, hopped around trying to get up.

Grandpapa gave an unsympathetic ‘Tsk!’ under his breath and called to Dench, ‘Throw Master Richard up!’

Dench clapped two dirty hands under Richard’s hopping leg and threw him up with as little ceremony as if Richard were a sack of meal.

My grandpapa was mounted on his hunter, a beautiful dappled grey gelding which stood rock steady, like a statue of a horse in pale marble against the background of the green paddock and the rich whispering trees of the Havering-Wideacre woods.

‘Remember her mouth is soft,’ Grandpapa told Richard. ‘Think of the reins like silk ribbons. You must not pull too hard or you will break them. Use them to remind her what you want, but don’t pull. I said, “Don’t pull!”‘ he snapped as Scheherazade side-stepped nervously on the cobblestones and Richard jabbed at her mouth.

Dench put a hand out and held her above the bit without a word of prompting. I watched uncritically. I had never seen a novice rider before and I thought Richard looked as grand as a Sussex huntsman, as gallant as one of Arthur’s knights. I watched him with eyes glowing with adoration. Richard on his own could do no ill in my eyes; Richard on Scheherazade was a demigod.

‘Let’s walk out into the paddock,’ said my grandpapa. There was an edge to his voice.

Dench led Richard out behind Grandpapa, his steady hand on the reins. He was talking to Scheherazade as they went past me, and I sensed that Scheherazade was anxious and felt uneasy. Richard on her back felt insecure. His touch on the reins fidgeted her.

I waited until they were some paces ahead of me before following. I did not want Scheherazade unsettled by footsteps behind her. It was Richard’s first riding lesson and I wanted everything to be perfect for him.

But it was not. I sat on the ramshackle fence and watched my grandpapa riding his hunter around at a walk and a trot in a steady assured loop and circle, and then calling to Richard to follow him.

But Scheherazade would not go. When Dench released her she threw up her head as if Richard’s hands were heavy on the reins. When he squeezed her with his legs, she sidled, uneasy. When he touched, just touched, her flank with his whip, she backed infuriatingly, while Richard’s pallor turned to a scarlet flush with his rising temper. But she would not do as she was bid.

My grandpapa reined in his hunter and called instructions to Richard. ‘Be gentle with her! Gentle hands! Don’t touch her mouth! Squeeze with your legs, but don’t pull her back! No! Not like that! Relax your hands, Richard! Sit down deeper in the saddle! Be more certain with her! Tell her what you want! Oh, hell and damnation!’

He jumped down from his hunter then and strode towards Richard and Scheherazade, tugging his own horse behind him. He tossed his own reins to Dench, who stood stoical, his face showing nothing. Grandpapa pulled Richard down from Scheherazade like an angry landowner taking a village child out of an apple tree, and, spry as a young man, swung himself into the saddle.

‘Now, you listen here, Sally-me-girl,’ he said, his voice suddenly tender and warm again. ‘I won’t have this.’ And Scheherazade’s ears, which had been pointy and laid back, making her head all bony and ugly, suddenly swivelled around to face front again and her eyes glowed brown and stopped showing white rims.

‘Now, Richard,’ said Grandpapa, keeping his voice even. ‘Like I told you in the yard, if you pull on the reins, you mean “stop” or “back”.’ He lifted his hands a fraction and Scheherazade moved forward. He pulled his hands a shade back towards his body, and she stopped as soon as she felt the tension on the reins. He drew the reins towards him again and she placed one hoof behind the other, as pretty as a dancer, and backed for three or four steps.

‘If you squeeze her with your legs, that means “forward”,’ Grandpapa said. He dropped his hands and invisibly tensed his muscles. At once Scheherazade flowed forward in a smooth elegant gait. She was as lovely as a fountain in sunlight. She rippled over the ground in a wave of copper. I clasped my hands under my chin and watched her. I ached with love for her. She was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my life.

‘But if you tell her to stop and go at once, then you will muddle her,’ Grandpapa said, letting her walk the circle while he spoke. ‘She feels you telling her to stop, and she feels you telling her to go. That upsets her. You should always be clear with animals – with people too!’ he said with a wry grin, taking his attention from her for a fraction of a moment. ‘She’s got a lovely pace,’ he said. ‘She’s a sweet goer. But she needs gentleness. Sit down deep in the saddle so that she can feel you there. And tell her clearly what you want. She’ll do anything in the world for you if you treat her well.’

He brought Scheherazade up to a mincing halt beside Richard and swung himself down from the saddle. ‘Up you go, lad,’ he said gently. ‘She knows her business. But you have to learn yours.’

He helped Richard into the saddle, and Richard got one foot into the stirrup, but he could not find the stirrup on the far side. He dug for it with his toe, trying to get his foot into the metal loop. Scheherazade at once side-stepped and bumped my grandpapa, who swore.

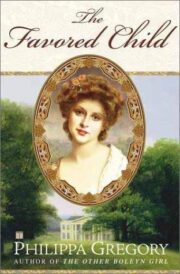

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.