‘Thank you, Mrs Gough,’ I said, surprised.

She gave me one of her rare smiles. ‘I hear all around you’re working hard on the land, Miss Julia. They do say you’re as good as Miss Beatrice was when she was a girl. I don’t hold with women owning land, but I know you’re getting it in good heart for Master Richard.’

I could have argued with that. I could have said that I was getting it in good heart for a dowry for James. Or I could have said that I was getting it in good heart to hand back to the people who worked it. But in truth, in those days, I was working in the same way that a sheepdog gathers the flock: I could not be myself and do anything else. It was as natural for me to farm the land as it was for me to breathe. So I held my tongue and just smiled at Mrs Gough and slipped out of the back door.

All at once the sight and smell of Wideacre tumbled over me like a spring flood over a waterfall. Before me the cedar tree showed the tiniest hint of lime green about its lower branches, and the rising sap oozed at the cut in its trunk where we had lopped a dangerous branch. I could hear a thrush singing, and from behind the house came the insistent coo of a wood-pigeon, trying out his voice after the season of silence. Behind the cedar tree was the paddock and the buds on the apple tree were as small as rice grains but scarlet with promise. Beyond the paddock the earth of the old meadow turned cornfield was white with frost, but away from the lee of the hedges I could see the weeds growing green, and beyond it and to my left was the common, rolling as sweet and free as wind-fetched breakers on an empty sea, yellow-brown with last year’s bracken and just a promise of green in the sleepy valleys.

To my right, southwards, were the high smooth folds of the downs, like green-velvet shoulders shrugging off the uneven borders of our fields, and I knew, although I could not see them, that the flock with the new lambs would be out on the fresh grass today. I stepped out into the garden and gulped in the scents, the sounds, the warmth of Wideacre on a sweet spring morning, and I felt my shoulders drop, and my lips smile, and my face turn blindly, like a winter mole, to the sunlight.

Minutes I stood there, half dazed and then – above the bird-song, above the pulse that was my own heart beating (though it sounded like a heart in the very land itself) -I heard a high sweet humming as if the waking earth were calling to me to come out and plough and sow and make it grow.

Ralph was already down at the field. We were starting with Three Gate Meadow, and then we would split the sowers into teams and ride among them to check the supply of seed-corn, the strength of the new ploughs and the ability of lads who had never ploughed a furrow before and men who had last ploughed fifteen years ago. I turned my mare towards Acre and Three Gate Meadow, with no one to break the daze upon me which came from the sudden sunshine and the promise of the day and the magic of Wideacre which was part of my blood and bone.

I slid from my mare’s back and tied her to the gate. The sowers were in the field, and their great bags filled with seed-corn bulged before them like the fat bellies of pregnant women. They had chosen Jimmy Dart – the lost son of Acre – to take the plough for the first wobbly furrow for luck. As I walked through the gate, I saw the plough coming towards me, his slight city-starved body hanging on to the handles for dear life, his weight too light to keep it straight.

‘Speed the plough!’ I called, and everyone waiting around the field turned and smiled at me and called, ‘Speed the plough!’ in return.

Clary was by the gate, a great bag of seed-corn over her shoulder and she gestured to me to take it from her. ‘Happy birthday, Julia!’ she said sweetly. ‘I’ve been waiting for you. You sow the first seeds. Everyone ’ud like it. It’d be good luck. Take a handful of seeds and just scatter them out in a big sweep.’

I half staggered under the weight of the bag and waited until the first furrow had been cut. The great horses bent their necks to pull the plough, knowing the work better than Jimmy. I stepped into the furrow behind him and dug deep into the bag that was weighing me down. The seeds stuck, moist and pale, to my hands and I threw them in a great flinging sweep out to the very boundaries of Wideacre so the whole green world should grow at my bidding and there should never be hunger on my land again.

Again and again I cast the seed in generous prodigal fistfuls, up to the sky as if I wanted the greedy wheeling seagulls to share in the bounty of the land so that there should be no crying – not even the crying of gulls on this day. In my head was a great sweet singing as the seed flew out in acres of silver and fell on the deep thick mud. I felt so strong, and so magical, that I half expected it to sprout as it fell.

I hardly heard the sound of hooves in the lane, I was so absorbed with keeping my balance on the heavy new-turned earth, and with the fascination of the damp sticky seed-bag and the sight of the flung seed. But then I heard someone call my name, and I looked around to the gate. There at the entrance to the field, sliding from his horse, with his black hair all curly and windblown and his eyes bright, was Richard.

I walked towards him in a dream, my hands still full of seed. He seemed to be the centre of the world whose heartbeat I had heard in my head this morning, his feet planted as surely as a rooted tree in the safe earth of Wideacre, his head warmed by the Wideacre sun.

The bedraggled muddy hem of my riding habit flapped around me as I staggered across the furrows, and the mud of Wideacre was caked on my boots. Richard reached out a soft white hand to me and drew me towards him, without saying a word. With the eyes of all of Acre upon us and with the plough-boys stopped to watch, I turned my face up to Richard like a common girl and let him kiss me long and passionately under the spring sky.

His arms held me tight to him and I was enveloped by his driving cape, which swirled around us. Sheltered by it, half hidden by it, I put my hands inside his cape and around his hard hot back, and clung to him as though I were drowning in the river. His head came down harder and I opened my lips under his and tasted his mouth on mine.

As if that taste had been poison, I suddenly leaped backward, struggling out of the folds of his cape, shrugging off his grip. Heedless of what he would think I put the muddy back of my hand to my mouth and rubbed hard, wiping away the taste of Richard’s tongue.

‘Don’t, Richard!’ I exclaimed and there was no magic between us, and no mindless delight left in me at all.

Richard’s face was as black as thunder. ‘I got your note…’ he started.

But then there was a warning call from Clary at the gate. ‘Look out, Julia, ‘tis your ma!’

I stumbled back another pace and looked guiltily down the lane. Uncle John’s curricle was turning from the drive into Acre lane and coming towards us, but I guessed they would have seen nothing more than Richard and I exchanging a hug of greeting. I coloured scarlet in a great wave of shame. I could not raise my eyes from the ground. I could not look around the field for fear of someone beaming at me, or winking at Richard. Even if my mama had not seen, it was not fear of her disapproval which made me recoil from Richard. I had jumped back from his embrace because his touch – which I had once loved so well-seemed suddenly heavy with evil.

I did not look at him. What he was thinking, I could not imagine. And when I thought of James, and of myself as his promised bride, I felt hot and kept my eyes down.

Not Richard. He always had a way of sailing through scrapes and he turned from me and strode up to the curricle. ‘Mama-Aunt!’ he said with delight, and leaped up to the step to give her a hearty kiss. ‘And Papa!’ he said, and stretched across my mama to shake John’s hand. ‘You will think me undutiful,’ he said, ‘but as I rode towards home I saw some people coming this way and they told me it was the first sowing day. I would not have missed it for the world. And here in the middle of the field was Julia, casting corn away as if she were feeding seagulls.’

Uncle John laughed. ‘We came to see the ceremonial ploughing, but I see we are too late.’ He nodded at Ralph, who came to the gate to greet them. ‘Good day, Mr Megson. Here is Richard home on a surprise visit for Julia’s birthday and to see your sowing.’

Ralph nodded to Mama and to Richard. I knew him well enough by now to know he could be trusted never to breathe a word that I had fled into Richard’s arms as if we were acknowledged lovers. No one in Acre would ever betray me on purpose. Only Ralph knew that I was affianced to another man and Richard should be no closer than arm’s length, but Ralph of all people would not care for that. I moved towards the plough and scowled at Ralph to warn him against teasing me. I might as well tell the sun to stop shining.

‘Hussy,’ he said in a provocative whisper, and I flamed scarlet again and frowned at him.

No one now would expect me to take my breakfast in the field with the sowers and the plough-boys but I was stubborn. ‘You go on home, Richard,’ I said pleasantly. ‘You will have things you wish to unpack. Have breakfast with Mama and Uncle John. I will be home as soon as ever I can, but I have promised to do a full day’s work here. If you want to come out again, I shall either be here or in Oak Tree Meadow. I cannot leave the ploughing now it has just started, there is too much for one person to watch alone. Mr Megson cannot be left with the work like that.’

Uncle John nodded his approval, but I saw the shadow cross Richard’s face. ‘I know everything comes second to the Wideacre crop,’ he said.

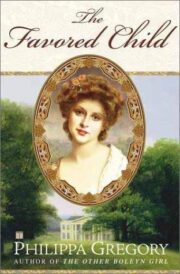

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.