I blinked. ‘No,’ I said. The clear impression I had was fading, going from me like a lantern on the back of a jolting wagon. Nothing I could see for sure.

‘You will send for me if you need me?’ he repeated.

‘Yes,’ I said, but I knew I would not be able to send.

‘And you know that I will come.’

‘Yes,’ I said again. But I knew he would not come.

John called from the coach. ‘Excuse me, Julia, excuse me, Mr Fortescue, but we must leave.’

We turned and went back to the coach. James handed me in without another word. ‘I won’t say goodbye,’ he said to me through the window. ‘I shall say God bless you until I see you again.’

I smiled at him, smiled as though I were not close to tears. And I waited until the coach had moved off and I could see him no more before I said, very sadly, very softly, ‘Goodbye, James, goodbye, my darling. Goodbye.’

We had an easy journey that afternoon. The children were in the hired carriage waiting for us outside the door of the Fish Quay Inn and we did not even stop to greet them. I waved from the window and they waved back – three beaming faces – and their coach fell in behind ours and we took the road east. It was comfortable travelling with my Uncle John. The carriage was warm, with wraps and blankets, and Mama and I had hot bricks under our feet. When we stopped to change horses, we were served with hot drinks in the carriage, and on the two overnight halts we had a private parlour with a bright fire burning, and even Mama laughed to see the children’s faces at the size of their dinners and the comfort of their rooms.

On the last morning, while Uncle John settled the bill, I went outside to order the carriage for the final leg of the journey. Jem Dench was very full of his own importance, cussing the ostlers and complaining of the looks of the pair. I glanced at them, but they seemed all right to me. The sun was overhead in a clear blue sky, but there were wisps of cloud on the horizon in that palest sparkling white which meant snow.

Above the noise of the stable yard and the clatter of wheels as another coach came in, I could hear a singing so high that it seemed sweeter and higher than the cry of bats, as if it were the music of the spheres which no one believes in any more, and so cannot hear. It sounded like a noise the snow-clouds might make on the eastward horizon where my home lay. It sounded like a noise which sunbeams might make as they slid down to warm me in the dirty little yard. I dug my hands deeper in my fur muff and leaned back against the inn’s door. Wideacre was calling me.

A lady in the coach looked at me curiously with the attentive stare I had met in Bath. I had filled out since I had left Wideacre. I had grown a little, and the Bath pastries had put some weight on me. I was as tall as Mama now. I wore heels as high as hers, and I had learned the knack of walking on them too! More than that, I had learned some poise and elegance from my long weeks in the town, and that sense which Mama called ‘the Lacey arrogance’ had put a tilt to my head and a way of walking as though I owned the land for a hundred miles in all directions, wherever I happened to be.

I gave a polite smile to the lady, and called to Jem that we were ready to go. He drew the carriage up beside me, and Mama and John came out into the yard.

‘Wonderful weather,’ Mama said as the coach rolled out of the yard and on to the high road again, followed by the hired carriage.

‘It may snow tomorrow,’ I said. ‘Or it may be snowing on Wideacre even now.’

It had frozen overnight and the ground was good and hard. Jem suggested going over the hills on the little tracks to Petersfield, and we took a chance that the roads would not be soft and the going difficult. We were right to gamble. The frost had made the mud firm, and we were rewarded for our daring by a drive through the sweetest countryside in England: the Hampshire-Sussex border. Best in Sussex, of course.

The beech hedges around the larger houses had kept their leaves and were bay-coloured or violet. The grass beneath them was white with frost, and until the sun melted it, every little twig which leaned over the road from the bordering trees was a little stick of ice: white perfection. The streams were not flooding but were small and pretty under the stone bridges of the roads; and it was warm enough for the children to play out on the village greens. This was the wider landscape in which my home was set, and I knew from the size of the streams, from the ice in the shadows and from the set of the wind how things would be at home. The land would be dry, crunchy with frost, but not frozen hard. The Fenny would be full but not flooded, and there would be little corners of the common and little hollows on the downs where it would still be warm enough to sit and put your face up to the winter sunshine.

We dropped down the steep hill into Midhurst, the brakes hard on and the wheels slipping, Jem whispering curses on the driving box. Then we rattled through the little town; the inns leaned in so far that the whip in the stock tapped on the walls as we went past. It was market day and the streets were full of people; the stalls were unpacked and wares were being sold in the square. I glanced at the price of wheat and saw it low – a sure sign of good stocks still with the merchants, and the likelihood of getting through the rest of the winter. There was the usual crowd of labourers looking for work, and some of the faces were pinched and pale with hunger. In one corner of the square there was a group of beggars, in filthy rags, blue with cold. Lying face down by some steps was a working man, dead drunk. I could see the holes in his boots as the carriage drove past.

Then we were clear of the village and trotting up the steep hill on the road towards Chichester. I felt my heart beating a little faster and I leaned forward in my seat and looked out of the window as if I could absorb through the very skin of my face all of Wideacre which I had missed for so long. The singing in my head was like a tolling bell calling me home, and the carriage could not go fast enough for me as we swept around the left-hand bend down the track towards Acre. It was only a short distance, and now I was in no hurry, for the trees on one side of the road were Wideacre trees, and the fields on the other side were Wideacre fields; and I was home.

Uncle John smiled at me. ‘You look like someone who has run a race and come in first,’ he said. ‘Anyone would think you have been pulling the carriage yourself, you look so relieved to be here.’

‘I am,’ I said with feeling. ‘It is so good to be home.’

We swirled in at the lodge gates and I bent forward and waved to the Hodgett children who were leaping at the roadside, then we pulled up outside the Dower House, and I caught my breath in my joy at my home-coming.

‘Now,’ said Uncle John, ‘I have a surprise and a half for you, Celia! See how hard we bachelors have worked to tidy the house for your return!’

Mama gasped. There was indeed a transformation. Ever since Uncle John had brought his fortune home, she had been buying little things to make the house more comfortable for us all. But Uncle John had worked a miracle. The old furniture of the house, which had been ours on permanent loan from Havering Hall, was all gone, and the little scraps of rugs which had been an attempt to make the house less echoey and cold had been thrown away. In their place were gleaming new rugs of fresh wool, and standing on them were beautifully crafted pieces of deep-brown teak and mahogany furniture.

‘It’s an enchantment!’ Mama exclaimed. Uncle John flung open the door to the parlour and showed us the room remade, the walls a clear, pale blue, the cornice newly plastered and gleaming white. A deep white carpet was spread on the shining floorboards and a brand-new round table and four chairs were standing against the wall. Mama’s favourite chair was in its usual place, but unrecognizable; it had been re-covered with a pale-blue velvet which matched the other chair seats, the window-seat covers and curtains.

‘Do you like it?’ Uncle John demanded, his eyes on Mama’s awestruck face. ‘It was the devil’s own job deciding on the colours. We nearly lost our nerve altogether and thought of writing to you to ask. But I wanted you to have a surprise.’

Mama was speechless. She could only nod.

‘But see the library!’ Uncle John said, as enthusiastic as a boy, and swept her from the room. All my childhood the library had stood empty. We had no volumes to fill the shelves, only the few reading primers and children’s books and Mama’s novels from the Chichester Book Society.

Now all that was changed. The walls glowed with the red of tooled morocco leather. There was a new great polished table in the centre of the room and a heavy chair behind it. A pair of easy chairs was on either side of the fireplace and matching little tables were within easy reach.

‘This is my room,’ Uncle John said with pride. ‘But you may look at my books if you knock before entering and stay very quiet while you are in here.’

‘I shall do my poor best,’ Mama said faintly. ‘But, John, you must have spent a fortune! And all this while Julia and I have been buying dress after dress in Bath, and renting lodgings, and giving parties, and I don’t know what else!’

‘I knew it was a mistake to let you go alone,’ Uncle John said gloomily, and then, seeing that Mama was genuinely concerned, he gave her a quick hug and said cheerfully, ‘My dear, there is plenty of money, and even if there was only a competence, you should still have a house in the town and one in the country.’

Mama smiled and sat on one of the new chairs.

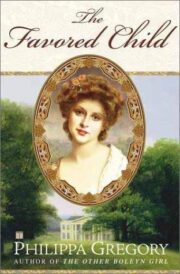

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.