Marianne sighed. ‘I look forward to being your first guest. But you are a little forward, James. The engagement has not even been announced, and I don’t think Julia has even told her mama.’

‘I cannot,’ I said. ‘She has been so ill and so tired, I did not want to trouble her. She would at once start planning parties and wedding gowns. I want her to be entirely well before she starts such a campaign.’

‘In the meantime, you must chaperon us,’ James said. ‘Do you have time tomorrow to go with Julia to Dr Phillips? We are to dispatch the Acre paupers in the afternoon, and Julia thought of seeing Dr Phillips first thing.’

Marianne agreed to escort me, and then go with me down to the inn to see that the four lost Acre children were ready to go home.

‘Would you like me to visit the doctor with you?’ James whispered softly to me as we said goodbye in the drawing-room while Marianne slowly tied on her bonnet before the mirror in the hall.

I hesitated. I was tempted to say yes and call on the help I knew he would give me. But I had been tempered in the fire of the most fashionable modiste in Bath, and I thought I could defend myself against Dr Phillips.

‘No,’ I said. ‘There will be much to arrange tomorrow. I shall meet you at the Fish Quay Inn; and I shall be a free woman then, for I shall have told Dr Phillips I shall visit him no longer. I should tell him on my own, face to face. It is only fair, for he has spent a deal of time with me, doing the best that he could. I am a little apprehensive, but it will be no worse than Mrs Williams’s shop. Nothing could be worse than that.’

‘And I was so much help there!’ James exclaimed. He took both my hands and took one to his lips and turned the other around to cup his face. ‘Keep me in your mind until tomorrow,’ he said. ‘For I cannot sleep at nights for thinking about you.’

Then he kissed me on my lips and strode out to the hall, swept up Marianne and was gone with a little smile for me.

‘I shall see you tomorrow at the doctor’s,’ Marianne called. ‘Don’t be late!’

I nodded and I was not late, for it was nine o’clock when I slammed the front door and started to run up the hill; I was still there ahead of Marianne. The solemn footman showed us into Dr Phillips’s bleak parlour like two twin flies for a plump spider at exactly five minutes after nine o’clock.

Marianne went to the seat by the window where my mama usually sat, and Dr Phillips waved me towards the comfortable seat before the fire. But I remained standing with one hand on the back of the armchair where I had poured out my dreams and nearly lost them altogether.

‘I have come to thank you and to bid you farewell,’ I said. ‘My mama has been unwell and as soon as she is well enough to travel, I shall want to take her home. They need me at home on the estate.’

Dr Phillips went behind his heavy wooden desk and leaned back in his chair, watching me over his folded hands. ‘I think that would be unwise,’ he said gently. ‘Unweasonable. Have you consulted your mama? No? Have you witten to your uncle? No?’ He smiled gently at me. ‘These things are genewally better done by pawents or guardians,’ he said. ‘When you first came to me, you were suffewing from a number of delusions. I am pleased to say that we have made inwoads. I think you have had no dweams since you came to me? And no experience of the singing in your head? And no hallucinations?’ He nodded to himself. ‘I think we have been making gweat pwogwess. I shall expect you to come again when your mama is well enough to bwing you, unless I hear to the contwawy fwom her or fwom your uncle.’

‘No,’ I said steadily. This was worse than the millinery shop, for I had no tide of anger to sweep me into certainty. ‘No,’ I said. ‘This is a decision I may take for myself. I will not be coming back to see you again. I shall tell you why,’ I said. My hands were trembling and I thrust them into my muff so he should not see. ‘You have indeed stopped my dreams, and I think in time you could have stopped the seeings altogether. But if you succeeded in that, I would no longer be Julia Lacey. I should be someone else. I do not know if I want that. I suspect that you have given no thought to that at all. You saw what you thought was a silly girl having delusions. But I believe that I am a special private person with special private experiences – with a gift, if you like – and I should resist being robbed of that as strongly as I should resist being robbed of my money.’

‘Has something happened?’ he asked acutely.

‘Yes,’ I said honestly. ‘Out of all the linkboys in Bath I recognized one as an Acre child, one who was taken from Acre ten years ago, one I had never seen before. I heard a voice in my head saying, “Take him home.” And I am going to take him home.’

Dr Phillips never moved, but his eyes were suddenly sharper. ‘Are you saying this is a pwoven experience of what is called second sight?’ he asked.

I shrugged with a little laugh. ‘I don’t know!’ I said. ‘I don’t care what it is called. It is as natural to me as seeing the colour of the sky, or hearing music when it is played. I will not have my sight and my hearing taken from me because other people do not have a name for it.’

He nodded, and rose to his feet. ‘Vewy well,’ he said. ‘But let me give you one word of warning. What you think of as second sight can be a guide in certain times and places. But you cannot be a seer and also a young Bath lady. Most of the time you would do well to be guided by convention and manners.’

I nodded. ‘Thank you,’ I said.

Marianne stepped forward beside me. ‘I too am saying goodbye,’ she said softly. I saw her face was white and strained but her teeth were gritted. ‘I thank you for the work you have done for me,’ she said, ‘but I want time to consider my own position without forever having to explain myself.’

Dr Phillips sat plump down on his chair again and looked at both of us. ‘My entire system depends upon the patient talking the twouble out of their minds,’ he said. ‘And I have a pwoven success wate.’

‘I have no trouble in my mind,’ Marianne said steadily. ‘My trouble is in my home where my mama is unhappy and my papa ill-treats her. The only time we ever see Papa is at mealtimes, and I am so distressed that I cannot eat. My papa pays your fees, Dr Phillips, and you have never wanted to hear this simple explanation from me. I understand that you will not hear it, but there is no reason in the world why I should go on pretending that all this is my fault, and that I can somehow be cured from the consequence of my parents’ bad marriage. I cannot eat at home because I am miserable there. I am miserable because my papa is unfaithful to my mama, and because they choose the family dinner table as a place for their disagreements. I will not sit in your armchair and talk and weep and blame myself any longer.’

‘Yes,’ I said softly. I felt more like shouting, ‘Hurrah!’ and throwing my bonnet in the air.

Dr Phillips got to his feet again and looked at us unpleasantly. ‘If this is the new wadical woman, then I cannot say I am impwessed,’ he said. ‘You may tell your mamas that I will submit my final bill and that I, not you, terminated our discussions. I find you both unsympathetic’

I bit back a retort, and curtsied in silence instead. Then Marianne and I got ourselves to the door and out into the damp street and around the corner into Gay Street before we whooped and laughed and congratulated ourselves, tumbled into a pair of sedan chairs and set off for the Fish Quay Inn.

They were in a delightful flurry of packing. All their new possessions, which James had provided, could have gone in one small bandbox; but the joy of private ownership was upon them and each had a separate box. Nat was now flesh-coloured all over his face, except for odd-looking sooty traces around his eyes, and he was very smart in a new suit. Rosie Dench was pale and thin still, but the sores around her mouth were healing and she did not cough at all. Jimmy Dart bustled around them both, as spry as a Bath sparrow in a brown homespun suit. I could not have recognized them for the sorry little crew in that dirty room. But I could not see Julie.

‘She won’t come,’ Jimmy said, his face losing all its light at once. ‘She won’t come with us. She’s in her room. She won’t even come down for her dinner before the journey. She says she’s staying in Bath. She only just told us.’

I looked around for James. ‘It’s as well,’ he said softly. ‘She could hardly ply her trade in Acre. And she could not do without drink.’

‘Trade?’ I said blankly. ‘I did not realize she worked. What trade?’

James made a little grimace. ‘Leave it, Julia,’ he said. ‘I’ll explain later. She does not wish to leave Bath, that’s all.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘She’s an Acre child. It is my duty to know what is happening.’ Ignoring him, I turned into the inn and ran up the stairs to the bedroom she shared with Rosie.

She was lying on the bed, fully dressed, with her face to the wall. The lattice window was shut, but you could still hear the noise outside of coaches coming and going and passengers calling orders about their bags.

‘Julie?’ I asked hesitantly.

She turned around to see me and her eyes were as red as her rouged cheeks. She had been crying. Oh, it’s you,’ she said. ‘Go to Acre with the others,’ I said intently. ‘You can go down now and take the coach with them this afternoon. Go home, Julie.’

She sat up and leaned back against the wall; her eyes were hard as Wideacre flints. ‘I can’t,’ she said blankly.

‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘Is there some trouble here?’

‘No.’ She said it like a sigh.

‘What is it, then?’ I demanded. ‘Why won’t you go home?’

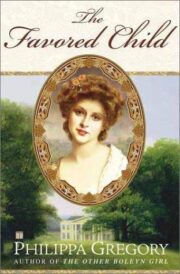

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.