I nodded. There was nothing I could say but yes. I took myself out of the room before they wondered aloud at the contrast between my bright healthy cousin and myself.

He was in the ascendant. He was the support of Mama and even of Uncle John, who relied upon him to carry messages to and from Acre. He was employed by Ralph Megson to do some of the tasks I had done. He was indispensable in the rebuilding of the cottages, and he was increasingly popular in the village. In those cold sharp days he was like a ploughing team testing a new harness. He kept trying a little more, he kept stretching his strength.

There was more and more he could do on the land. John’s gentle old hunter was glad of a little ambling exercise, and Richard gained praise from Uncle John for not despising him. In truth, Richard had never looked so happy with a horse as he was on that easy-tempered animal who looked showy and was bred well, but was so near retirement as to be as safe and as comfortable as an armchair.

I had become nothing to Richard. He had the land, he had Acre, he had some village flirtation.

I had become nothing to Acre. I had worked for them and saved them. And now they were ready to rebuild and turn their faces to the future. They would forget me in weeks.

I had become – not nothing, no, I did not imagine that – but I had become a source of worry and unease to my mama and to Uncle John. I was not a favoured child. I was a very troublesome one.

I went into the parlour with my cheeks burning and my eyes bright, and when Uncle John and Mama came in, I caught a glance between the two of them brimful of worry and concern. They thought I was moody, or volatile, or hysterical. Indeed, I felt that I was all three.

I went as close to my mama as I could go, as though her mere presence could keep me safe from the appearance of madness, and from the feelings of madness itself, the panic that I was losing everything and my dread of being that barefoot woman of my dream. I pulled up a footstool and sat at her feet and helped her unpick the hems of gowns which we were taking to Bath to be remodelled. I unstitched like a careful sempstress, detaching the antique lace which would be used to trim new gowns. I took it to the kitchen and washed it and rinsed it with meticulous care, and then patted it with a soft linen cloth and spread it out to dry.

Richard was out at work all day and did not come home until dinner-time. They had ordered dinner to be late to suit his convenience. I was beyond impatience or jealousy or anger. Richard was the squire. He would do as he pleased.

He came home late, as he had said he would, and threw down his cape over the banister and ran up to his room to dress. I could smell the frosty air in the folds of the wool and it called me, as clear as a voice calling my name. I threw on a shawl and went out of the front door and around to the back garden where I could see the dark shadow of the downs, black against a blue-black sky.

The grass was crunchy with the frost, and the sky was an arch of darkness with sharp stars. A shadow went across the sky and I heard an owl call a long clear hunting note. The great cedar tree stood like a splay-fingered giant against the starlit sky. A figure moved out from the shadow and came near to me.

It was Clary Dench. ‘Julia?’ she said. ‘It’s me.’

‘Oh, Clary!’ I said. ‘I am so pleased to see you!. How did you know I needed you so badly?’

‘I was to see Richard,’ she said, ‘after work, in the woods. But I was late and he was gone. I thought it would be a message from you for me. So I came on up here.’

‘You were meeting Richard?’ I asked incredulously. ‘Meeting Richard after dark in the woods?’

Clary gave an unladylike whoop of laughter. ‘Don’t be a fool, Julia,’ she begged me. ‘What d’you think I am? Some daft village slut chasing after the boy squire? He asked me to meet him and I thought it was a message from you. Why else?’

I nodded slowly. It was another thread of Richard’s skein of teasing and misreading which was winding around me and colouring my world.

Oh,’ I said. Oh, but Clary, it’s good to see you!’

I put an arm around her waist and hugged her and felt the familiar warmth of her plump body and the familiar tickle of her long hair against my cheek. We turned and walked across the lawn together, and stopped at the foot of the cedar tree. I rubbed my hand against the bark, feeling the flaky contours, smelling the sweet spicy scent of it.

‘I’m glad you’re here, because I have to say goodbye to you,’ I said. I put my hands out to her. ‘I’ve not been allowed down to Acre since the night of the storm, Clary. They say that I am ill, and in truth they are half-way to making me believe that I am. They are sending me to Bath tomorrow, and I dare say I won’t be allowed down to say farewell to my friends. Tell them in the village that I thought of all of them, and that I sent them my love.’

She held my hands between two cold palms. ‘Going?’ she said blankly. ‘Going from here? What for, Julia? Are you going for long?’

I tried to laugh and say, ‘Oh! Of course not!’

I tried to smile and say, Oh! I shall have such fun in Bath!’

But instead I found I had sobbed aloud, and flung myself into Clary’s arms and said piteously, ‘Oh, Clary! Clary! Just because of the dream and because of the night of the thunderstorm, they think that I am going mad and they are taking me away from here and I don’t know what will happen!’

And I wept for the first time since Richard had warned me that I must not seem odd, and felt the fear and the anxiety ease from me as Clary patted my back, and dried my face on her thin shawl, and then pulled me over to the swing – ghostly on its frozen ropes – and sat me down.

‘What is wrong?’ she asked gently. ‘You are not in the least mad, but I have never seen you so unhappy. You look odd too.’

‘How odd?’ I asked afraid.

‘Older,’ she said, fumbling for words. ‘Sad. As if you knew something awful. What’s happening, Julia?’

I had a lie, a lie for my dear Clary ready on my tongue, and I was poised, one toe on the ground, to set the pendulum swinging so that I could lie, and swing backwards and forwards like a clock telling the wrong time. But I did not launch myself. I kept my toe on the ground and then I slowly eased the swing down into the upright position again. I did not want to lie to her. Whatever might be going wrong, there were some things in my life which went back a long way, which I wanted to keep safe.

‘It’s Beatrice,’ I said slowly. In the still garden, drained of colour, Clary and I faced each other, the horror of what I had said smiling at us both. She shivered, although her shawl was wrapped tight around her; and I knew that same chill inside me.

‘It is Beatrice and her magic,’ I said in a whisper.

Clary’s eyes were dark with fear and I could feel the hairs on the nape of my own neck prickle like a threatened dog’s.

‘Are you seeing her?’ she asked, her voice soft.

‘No,’ I said in an undertone. ‘It is worse than that. I feel as if I am becoming her.’

There was an utter silence between the two of us. The little wind blew the smell of the cold downs to us, but underneath there was the scent of fear, sharp as sage.

‘Was it when Ralph Megson arrived?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘He heard her then in my voice. I think he even saw her likeness then in my face.’

She nodded and put out a hand to tighten her shawl around her. With a prickle of fear up my spine I saw that her hand was clenched in the old sign against witchcraft, the thumb between the forefinger and the third finger to make the cross. I leaned forward and put my hand over hers, imploring, accusing. ‘Clary, you make that sign to me?’

She flexed her fingers and dipped her head, and in the starlight her face grew dark as she blushed. ‘Oh! Lord love you, no!’ she said. She turned away from me and went to the trunk of the cedar tree and rested her head against the trunk as if to clear the whirl in her mind by the touch of the bark. ‘No,’ she said, turning back to me and leaning against the tree-trunk. ‘I did not make that sign to you. But I did make it to something I saw. I saw something in your eyes, Julia. It had me scared, I admit it.’

‘You see her in my eyes,’ I said blankly.

She looked at me with the eyes of a friendship which went back to the time when we were just little children playing in the woods. ‘Yes, I suppose so,’ she said. ‘It’s nothing more than they’ve been saying in the village all this year. That you are the favoured child. That you are her heir.’

‘It doesn’t feel much like being favoured,’ I said resentfully. ‘I have had a dream, oh, Clary, such a nightmare!’ She said nothing. ‘Not a nightmare like one of my dreams of Beatrice,’ I said. ‘Just a feeling of being utterly alone. So terribly, terribly alone and with no one to love me, and no one to love at all. No one to love except a little tiny baby in a white shawl, and knowing I have to drown her.’

Clary gasped, her face white in the moonlight, then she came towards the swing and knelt on the frozen grass at my feet and put her hands on mine. ‘I will always love you,’ she said in the deep sweet drawl of Acre. ‘I will always be here.’

For a moment I was warmed by the affection in her voice, but even as I started to smile, I heard a noise, like an icy wind blowing from far, far away. ‘No, you won’t,’ I said, and we heard the desolate certainty in my voice.

For a moment Clary’s eyes questioned me, but she was a village girl and wise. She shrugged her shoulders and gave me a gleam of her defiant urchin smile. ‘Well, at least I shan’t have to put up with the sight of you lording it as squire, then,’ she said.

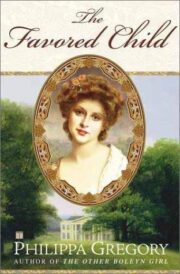

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.