‘Very much,’ I said. Then I remembered what Richard wanted of me. ‘But more than anything I am looking forward to seeing Richard as squire in a proper hall.’

‘And speaking of fresh starts and new plans,’ Uncle John said, smiling, ‘I think it is time the pair of you started learning to ride in earnest. It is Chichester horse fair today, and I am going with the hope of buying a useful hunter for myself, and I have a mind to buy a horse each for you. If I can find something suitable.’

I did not say a word, I could not speak. I realized my hands were clasped under my chin and I had half risen from my seat, but I said nothing.

Richard was oddly silent too.

‘I will assume that silence betokens consent,’ Uncle John said teasingly.

Oh, yes!’ I said longingly. Oh, yes! Oh, yes! Oh, yes!’

Uncle John laughed, his eyes on Mama. ‘They really are delightful, Celia,’ he said, speaking over our heads as if we were very small children. ‘They truly are delightfully unspoiled, I agree. But Wideacre or no, they must go to town and university and have a little polish rubbed on them.’

‘Dreadful!’ Mama said. ‘Julia, you put me utterly to the blush! Stop saying, “Oh, yes” like that and say, “Thank you,” as though you had a ha’p’orth of wit. And, Richard, it’s not like you to have nothing to say for yourself.’

Richard cleared his throat. ‘Thank you, sir,’ he said politely. I think only I could hear the lack of enthusiasm in his voice, and I had a twinge of remorse and sympathy for Richard. I guessed he was thinking of Scheherazade.

‘Thank you, Uncle John,’ I said softly. ‘Mama is right and I have no manners at all. I was just so…so…so…’

Uncle John smiled at Mama as I ran out of words.

‘Boarding-school?’ he suggested.

‘Bedlam!’ Mama replied. ‘Julia, if you have nothing to say, you can go and fetch some writing-paper and ink for me, instead of kneeling there on the floor with your mouth open. Richard, it must be time for you to go to Dr Pearce.’

Richard bowed to her and bid us a general farewell and then took one last lingering look at the exquisite drawing, like a hungry man looking at a meal which might be taken from him. ‘Yes,’ he said unwillingly, and went to the door.

I waited for a smile from him, but I had none. He went from the house with his head down and not even a glance towards me, though I stood in the hall as he shrugged on his greatcoat and was at the front door when he went out. He went without a look at me. He went without a word to me, though he knew I was waiting patiently for either. I stood at the parlour window and watched him stride down the drive, watched in case he relented and waved to me, but he did not. Mama saw my stillness and my eyes upon his vanishing figure when she came into the parlour.

‘Will you write some letters for me, my dear?’ she said invitingly.

‘Yes, I will,’ I said without hesitation.

She looked at me closely. ‘Is Richard still angry with you about John Dench?’ she asked softly.

I did not have tears in my eyes. I did not feel an ache in my heart. I did not feel the sense of dread which I learned in childhood when I thought of Richard’s rage. I gave a little impatient grimace. ‘He’s in the sullens,’ I said, unimpressed. ‘He’ll get out of them.’

And ignoring Mama’s look of surprise, I sat up at the table, collected some notepaper, dipped the pen in the standish and set to writing to her dictation as if I had never cried for Richard’s approval in my life.

Uncle John was lucky at the horse sales; but Richard and I were not.

‘I could see nothing which would suit either of you,’ he said. ‘I am sorry to disappoint you, and I am disappointed too. I had promised myself the pleasure of coming home in the carriage with three horses trotting behind me. I found this grand old hunter for me, but nothing suitable for the two of you.’

‘What was the problem, sir?’ Richard asked courteously.

We were sitting down to a late dinner, and Uncle John smiled down the table at Richard as he carved a plump goose into wafer-thin slices and Stride passed them around.

‘Bad breeding,’ he said briefly. ‘I wanted something steady and sound for both of you, but something with a bit of breeding so that you could have more fun when you were used to riding. I’d have looked for something fairly lively for you, Richard, don’t fret! And something slow and steady for Julia. But there was nothing except some broken-winded hunters who would never get out of a trot without gasping like a landed fish.’

Richard laughed heartily. I watched him closely. He was out of his ill humour with me, and he seemed relaxed, even pleased. I could not understand it. I was trying very hard not to seem sulky, but I was so disappointed at Uncle John’s bad luck at the horse fair that I could have wept.

‘Perhaps you have saved your money, sir,’ Richard said. ‘I was thinking that, as I am going to Oxford, you would have bought a horse for me for nothing. I could not ride one there, I suppose?’

‘No,’ Uncle John agreed, carving the last slices of goose and sitting down to his own place. Stride served him with crunchy roasted potatoes, some succulent carrots from the Havering kitchen garden and roasted parsnip. Uncle John waved away the gravy, but took a liberal helping of Mrs Gough’s smooth lemon sauce. ‘But I had thought, Richard, to keep your horse here for you to use in the holidays. That is no great burden on the stables, you know.’

Richard smiled sweetly. ‘You’re kind to me, sir!’ he said. ‘But since you have had such trouble in finding a suitable horse at this fair, I do beg you not to trouble yourself any further. I have walked around Wideacre all my life, and am well able to continue to do so in the meantime. I am sure Julia feels the same.’

I opened my mouth to disagree, but a sharp blue look from Richard silenced me.

‘At any rate, there is no need for a horse this summer,’ Richard said smoothly. ‘I know Julia’s grandmama does not approve of ladies riding in summertime, and I am happy to go horseless to keep my cousin company.’

Mama smiled. ‘That is sweet of you, Richard!’ she said approvingly, and Uncle John nodded. ‘And he is quite right,’ she said to John. ‘It is not really the season to start to learn to ride. If there are no good horses available, perhaps the two of them can wait until the Christmas holidays.’

Uncle John shrugged. ‘As you wish,’ he said. ‘I should have liked to have produced two horses for the pair of you without further ado, but there is certainly nothing suitable in the neighbourhood for sale at the moment. I shall keep my eyes open for you both, you may be sure. If we cannot find suitable riding horses, then you will have to drive around and I shall get a cob or something to pull the gig.’

I bit my lip and looked down. I seemed forever to be getting so close to having a horse and then being disappointed.

Mama saw my downcast face and smiled sweetly at me. ‘Never mind, Julia,’ she said. ‘We will order you a riding habit when we are next in Chichester and then at least when we find the right horse, you will be ready to ride at once.’

‘Thank you, Mama,’ I said, trying to sound pleased. And I turned my attention to the roast goose as if I had been fasting all day.

‘I met Lord Havering in Chichester and told him some of my ideas about the revival of the estate,’ Uncle John said. ‘He was kind enough to call them radical poppycock!’

‘You did not quarrel?’ Mama asked with an anxious frown.

‘Most certainly not,’ John said. ‘It takes two to make a quarrel, and his lordship made sure I did not have a word to say. I told him some of the ideas I had and he was torn between laughter at my naivety and rage at my revolutionary opinions.’

‘Are you a revolutionary, Uncle John?’ I said, regarding him with some awe.

‘Compared to your grandpapa, I am a veritable traitor to the State!’ Uncle John said cheerfully. ‘But in all seriousness, Julia, I am just one of very many men who think that the world would be better run if the nation were not divided into a vast army of workers – something like six million people – who have no land, and a tiny minority – some four hundred families – who between them own it all.’

‘What would you do?’ I asked. ‘What would you do to change things?’

‘If I were made king tomorrow,’ Uncle John said, smiling, ‘I would pass a statute which would give everyone equal shares in the land, and order them to work in communities and farm the land all together. Everyone would have his own house and his own patch of private land, his own little garden and his own animals – see, Celia, I am not against private property, whatever your step-papa says! – But everyone would work together on land which was held in common. Like the old village fields when the elders of the village decided what was planted and how it was to be done.’

‘Hurrah for John’s kingdom!’ I said, and Uncle John laughed at my bright face.

‘I have a convert,’ he said to Mama. ‘There is no need for you to look so grave, Celia. I have a convert and the future is on my side.’

‘What will you do before you become king of England?’ she asked. ‘How will you explain to Acre that the golden age has come around again?’

‘I shall consult my adviser,’ he said solemnly and turned to me. ‘Prime Minister, Miss Julia: how shall we persuade Acre that they must all work together and take a share in the profits?’

I thought for a moment. ‘Is it a serious plan, Uncle John?’ I asked. ‘Do you really want Acre to share in the profits of the estate?’

‘I’m tempted,’ he admitted. ‘I spent many hours in India reading and thinking about what went wrong on Acre. It seemed to me then that the only way to run an estate justly is if everyone has a say in how it is to be run and a slice of the profits.’ He paused and looked at my intent face and Mama’s doubtful one. Richard was listening with his habitual courtesy.

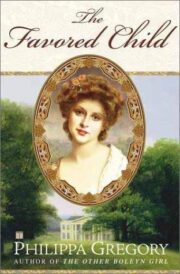

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.