‘You listen to servants’ tittle-tattle and you’ll get false reports,’ I said disdainfully. Richard flushed dark red. ‘I spoke to no one,’ I said coldly. ‘But you need not reprimand your spy for getting things wrong. He will not again ride behind me when I drive. Not to Acre, not to a bishop’s tea-party. I won’t have a dirty little spy in my employ. So you can dismiss him, or, if he is on the box, you will be alone in the carriage.’

My head held as high as a princess’s, I swept from the room and did not stop until I reached my bedroom door and shut it tight behind me. It was a gamble. No one knew that better than I.

But if I could face Richard down when he was afraid of the rumour of Ralph’s return, if I could look at him with eyes of burning scorn when he had, indeed, caught me out, then I thought I might have some sort of future on the land.

Acre was smiling again. Acre had once more the impertinent grin of a community which knows itself to be badly mastered and recks little what the masters say. I thought that even I, in the big house, in the bed of the squire of Acre, might learn that courage too.

I undressed, but I kept on Mama’s rose-pearl necklace and her ear-rings. They comforted me a little as I slid between the cold sheets. Since the baby had grown so large, I had taken to sleeping on my back with my rounded moon-shaped belly pointing at the ceiling. I sprawled out in the bed and sighed as the little kicks and wriggles started, making my own body leap like a net of eels. Sometimes I loathed this child as the misbegotten heir of Wideacre, sometimes I adored it as the fruit of my body, my own child. And sometimes, like now when I was tired, I just sighed like any pregnant woman and wished the hours away and the sleepless night over.

The baby was quieter than usual, and I fell asleep by candlelight, forgetting to blow out the flame. So Richard was in my room, and naked in my bed, before I was awake and before I could stir myself to protest.

He had one hand over my mouth in case I should cry out, and the other, urgently, pulled at my nightgown. I could have bitten his hand, I suppose. The palm was salty against my teeth, and it felt dirty. But I did not think of doing it.

I did not think of doing it.

I was shamed that I did not think.

I thrashed a little, under the sheets, encumbered by the great belly on me and the tucked-in covers. I gave a little smothered moan behind his hard hand, and he saw my eyes widen in distress and darken with horror. But he smiled his blue-eyed devil’s smile, and I knew then that the madness was on Richard and that it might – at last, at last – be the end for me tonight.

It was not lust for him. It was not love or desire, nor any hot half-forgivable sin. It was power and cruelty which were driving Richard onward. He had seen the tilt of my head, he had seen the bright courage in my eyes, and he had waited until I was asleep and unguarded, and then he had come for me. He was in my bed, his hand hard on my face, his other hand pulling up my nightdress and his weight coming down on top of me.

He drew the hem of the gown up to my neck, and I froze as his hand brushed across my throat, across the pearls. I knew he was thinking longingly of throttling me as I lay there, eyes wide with fear, beneath him.

When I saw him smile, I knew I was lost.

I was ready. I had promised Mrs Tyacke, I had promised Mrs Merry with all of Acre listening. I would not give them another squire to rule over them. I would end the line of the Laceys. If Richard killed me tonight, that would be the end of me and of Richard’s heir – and of Richard too, for they would have to take him up for my murder. I gritted my teeth at the discomfort of the weight of him on top of my rounded belly, and at the distasteful hand against my mouth. And I gritted my teeth for courage and said a swift farewell in my mind to the things I had loved-to James, to Wideacre, to Mama. For I was readying myself for death.

He was heavy. He was half on me, half beside me. The weight of the unborn child kept me pinned to the bed. He put his hand back on the great swelling of my belly and stroked down the slope when his devil-begotten child shifted uneasily as if it knew my fear.

Oh, Julia,’ he said longingly, half to himself. ‘I had forgotten this. It is only this that saves your life tonight.’

I tried to keep my face impassive.

‘I meant to strangle you,’ he said dreamily. ‘I am sick of your long face around the house. There are other women I could have here if you were gone. There are other girls I could marry. I wanted you because you had Wideacre, but now it is mine, and I want you no more.’

The candle guttered, throwing menacing shadows on the ceiling above me. But nothing was more menacing than the shadow which was in my bed, which spoke such obscenities in such an intimate whisper.

‘I did love you once,’ he said as if he needed to reassure himself. ‘When we were very little children, before we knew who we were, or what we were to inherit. I think I loved you then.’ He broke off. He was talking to himself; it seemed he was in a dream of other times.

‘I loved Mama-Aunt too,’ he said. His voice was suddenly higher in pitch, childlike. I realized with an instinctual shudder that Richard had gone. He was back in the sunlight of his Wideacre childhood with an aunt who adored him and a cousin who would cross the world for him. The world where he had been the beloved little tyrant.

‘I loved Mama-Aunt so much,’ he said sweetly. A shadow crossed his face. ‘But you were always trying to be first in Acre,’ he said, cross as a petulant child. ‘Always trying to come between me and Mama-Aunt. You would push in where you were not wanted, Julia. And though I could forgive you if you were very, very sorry, I could not help but be so angry, so very angry, with the people you tried to take away from me . . . Are you listening to me, Julia?’ Richard said with quick irritation.

I nodded, as obedient as a child in school. His grip had tightened on my mouth again. I feared I was going to retch at the smell of his hand against my teeth and gums, the odour of horse-sweat, cigar smoke, Hollands gin. And beneath it all the heart-wrenching smell of Richard, the cousin I had loved for so many years. So very many years.

‘I killed her,’ he said, speaking, at last, the unspeakable. ‘Your friend Clary. I tried and tried to be friends with her. I even tried pretending I was in love with her. She laughed in my face!’ His voice was shocked. ‘She said you were worth ten of me.’ He paused. ‘I knew I’d pay her out for that.’

I watched him, and said nothing. His blue eyes had become hazy.

‘She saw us,’ he said, ‘when I raped you in the summer-house. I looked up and saw her. I think she was going to nm towards us, to help you. But she saw my face. She ran off as fast as she could towards Acre. I expect she thought to get help. I caught her at the Fenny,’ he said languidly. ‘I put my hand around her throat. She was like you, actually, because she was quite strong too. But do you know, she was so afraid, she hardly fought at all. She just choked and then her tongue and her eyes came out. Rather horrible. She looked so nasty I pushed her in the river and went home. I knew it would be all right for me. Everything always is all right for me.’

He sighed quietly. ‘I killed your mama too,’ he said. A petulant expression crossed his face; I could see the droop of his disappointed mouth in the firelight. ‘She was running off with John. That was so horrible for her to do such a thing. She had joined with John against me. She sent me away as soon as he came home. I had thought she was a beautiful woman, a wonderful woman. A woman like an angel. But she was just a whore like all of them. Like you. As soon as my father came home, she was running after him like a bitch in heat. She forgot all about me. It was his idea to disinherit me, and she was going to do anything he wanted. She was going to overturn our marriage, and I would have been disinherited.’ He paused. His face became calm again, his words measured, judicious. ‘That was a very bad thing to do. You do not understand business, Julia, because you are just a woman, but that was a very meddlesome thing for Mama-Aunt to do.’ He paused again. ‘I am surprised she dreamed of it,’ he said simply, with grave respect. ‘She was, apart from that, such a feminine sort of woman.’

I lay as still as stone. I could feel my heart beating and I knew that in a moment the sound would remind Richard that underneath him, in his power, was another woman who had forgotten her place, who had tried to meddle with the ownership of the land.

‘It hurt her, I am afraid,’ he said regretfully. I half closed my eyes. I had to hang on to some shred of myself, some remnant of sanity not to cry out, not to scream at these words, as Mama’s murderer lay on top of me and told me in his sweetest voice the horror that I had tried all these months to evade.

‘It hurt her,’ he said again. ‘I shot Jem at once, you know. And then, with the other pistol, I shot John through the window. He had opened the door and was coming out at me. Rather brave of him, really. He was trying to protect Mama-Aunt, I expect. The shot threw him back into the carriage, over her knees, actually. She screamed. I expect the blood frightened her. But she didn’t do anything.’ He hesitated. ‘Well, there was nothing she could do really,’ he said fairly. ‘I was reloading, but that doesn’t take long. Then I waited.’

His hand was slack on my mouth again, his mad blue gaze dreamy in the candlelight. This time I could not have moved. I was frozen with horror and with a macabre fascination at his story.

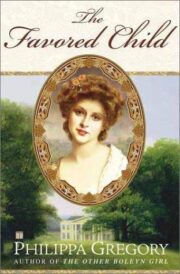

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.