‘Get me a copy of that newspaper, Stride,’ I said levelly, my eyes on my letter once more.

‘Yes, Miss Julia,’ Stride said, his tone equally neutral.

He must have sent to Midhurst at once, for he had it at coffee-time and brought it to me in the parlour with the silver tray and the coffee service.

I did not have to scan the columns. The story which had sent Richard from the room was on the first page inside. It was headed: ‘Notorious Rioter Escaped’, and it named Ralph Megson as among three men who had broken out of the prison disguised as members of a gypsy family who had been brought in to play for the prison warders. It was thought that the men had fled with the gypsies and would travel with them. There was much lordly huffing and puffing and alerting of the local Justices, but there was also a clear acknowledgement that three men could easily disappear into that secretive underworld and never be seen again. There was a detailed description of Ralph, and of the other two, and a massive reward of two hundred pounds for information leading to the capture of all three.

That reward made me pause and wonder if there could be any safety for Ralph. Then I thought that Ralph was not a man to be taken by surprise, except on that one time when he had been betrayed in Acre. I did not think he would be betrayed by his own people, by his mother’s people, his gypsy family. And I had a shrewd idea that Ralph would know exactly how long they could be trusted to resist the lure of such a fortune, and he would be away on a smuggler’s vessel the day before temptation became too great.

I squeezed each page of the newspaper into a ball and tossed them one by one on to the fire, and watched each little ball flame and blacken before I took up the poker and mashed up the ashes. I did not want Richard to know that I knew about Ralph.

That was the first time in my life I had effectively conspired against Richard.

He did not come home for dinner, and Stride served me in solitary state at the great mahogany table. I sat with a book beside my plate, a novel from the Chichester circulating library, and between mouthfuls I read about Clarinda’s wants and needs, and her unfailing tenderness for the hero. I wondered a little whether I should ever again be a woman who thinks that love, a man’s love, is worth the world, or whether from now on I would always feel that one’s own freedom, one’s own individual pride, is worth so very much more.

I took my novel with me into the parlour, and slouched in my armchair to read it. But I laid it down often and looked into the fire. I had not thought to feel happiness again. But Ralph was free, and some bars had gone from my inner eyes. Ralph could look up at the sky tonight and see the sharp light of the stars which means that it is going to snow. Ralph could see that halo around the moon which warns of frost. Ralph could face north, south, west or east, and go where he willed again.

I hoped he would guess that I had learned my lesson, that although I sat at Richard’s fireside on Richard’s furniture in Richard’s house on Richard’s land, I knew at last that I was dispossessed. And that I had become, at this last, a Lacey woman who knew that it was the ownership of the land which mattered more than the chimera of love.

But I thought also that I was a new version of a Lacey, because I rejected the Lacey right to own the land and its crops, and the people themselves. If it had been mine again, I would have given it away at once, without hesitation and mumbling of profits. I would have given the land to Acre, to the people who work it and live on it. And I wished very much that I could see Ralph just once more to tell him that I at last knew what he had been trying to teach me. That there can be no just squires, no kindly masters. For the existence of squires and masters is so deeply unjust that no gentle benevolence can make it right.

I had had to become a servant, Richard’s servant, before I knew the injustice of servitude. I had had to be a pauper, Richard’s pauper, before I learned that dependence is a death sentence. And the only want that was left me, the only wish I had, was that I might see Ralph once and tell him that I understood, that I too was an outlaw from this greedy world we Quality had made.

Stride tapped at the door and came in with the tea-tray, and Richard walked in behind him. He had been riding and was not dressed for dinner. He asked Stride to bring more candles and sat opposite me on the other side of the fire as though nothing were wrong. But I saw he was as tense as a trip-wire, and he glanced at the curtains when they stirred in the draught.

‘I have been to Chichester,’ he said without preamble when Stride had set a five-branch candelabra on the table and gone. ‘I read some news this morning which disturbed me very much.’

I raised my eyes from the tea things and their gaze was as clear and as warm as the wintry sky.

‘There was a report.’ Richard spoke with some difficulty. ‘There was a report in the paper that some men had broken out of the London prison where Ralph Megson was held. You remember . . .’ He broke off. He had been about to ask if I remembered Ralph Megson, but not even Richard had sufficient gall for that. ‘I went to Chichester to seek more perfect information,’ he said. He took his dish from me and a drop of tea was spilled on the cream hearthrug. Richard’s hand was not steady. ‘It turns out that the report is true,’ he said. I inclined my head, and took up my own dish.

‘Magistrates have been warned to be alert for gypsies,’ Richard went on. ‘Gypsies or travelling folk of any kind, The three men escaped with some gypsy musicians. It’s thought they may try to get to the coast travelling with a gypsy family.’

Richard stopped talking and glanced at me. My face was impassive; he could read nothing from it. ‘Do you think he would come here, Julia?’ he demanded. ‘Do you think he would come here with some sort of idea of revenge? Do you think he would come here and hope that Acre would hide him?’

Richard’s voice had his old charming appeal. He needed me. I had always been at his side when he needed me. Indeed, it had been the joy of my life to have him need me, to have him ask for my help as he was asking for it now.

‘I think he might blame me for his arrest,’ he said with driven candour. ‘I spoke to the magistrates in Chichester, and they said there was little they could do to protect us, us Laceys, Julia! Unless we had some clear idea of where he might be.’

Richard put down his dish of tea and held out his hand to me. ‘Julia?’ he asked. It was as if we were small children again and he was in trouble, as if he were a little boy whose scheme of mischief had gone badly wrong, calling for his best friend, his sister, to help him.

I held my tea with both hands. ‘Yes?’ I asked.

‘Do you think he would come here?’ Richard withdrew his hand and put both hands together on his knees, ignoring the slight.

‘No,’ I said honestly. It is not my way to tease and torment a person. And I spoke with regret. I was very sure I would never see Ralph Megson again, and I thought myself the poorer for it.

‘Not with the gypsies who winter on the common?’ Richard said eagerly. ‘They come from London way, don’t they? And they are late this year! It would not be them who got him from prison, would it? They are musicians too, remember, Julia! We had them to play at Christmas, do you remember?’

I nodded. I remembered. I thought I remembered everything in a great long tunnel of pain back to my childhood and babyhood when I had loved Richard and loved Wideacre with a great constant rooted love which I thought nothing would ever spoil or change.

‘I remember,’ I said. ‘But I should have thought Mr Megson’s safest course would be to take a ship out of London. He had many seafaring friends too.’

‘You don’t think he would come here?’ Richard insisted. His eyes on my face were as urgent as those of a child woken from a nightmare, demanding reassurance.

‘No,’ I said steadily. I was not rescuing Richard from his fears to oblige him. There was that deathly coldness around my heart still which made me think that I would never again wish to help anyone, least of all Richard. But I was too remote from him to tease him either.

‘If he came here, would Acre hide him?’ Richard persisted. ‘They hid Dench the groom, remember, Julia!’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I never go to Acre these days, Richard, you know I have not been there since the autumn. You must know better than I what the mood of the village is. Would they hide an enemy of yours? Or do they cleave to the Laceys?’

Richard jumped from his chair in sudden impatience, and some cold quiet part of my mind thought yes, you are truly afraid, are you not, Richard? You who have done so much to make so many people afraid of you. All of Acre, and Clary who must have looked in your face before she died in terror, whose fear is so unbearable to me that it is walled away in a rose-pearled corner of my frozen mind. And now you are most bitterly afraid.

‘I want you to go to Acre,’ Richard said suddenly. ‘I want you to go down there tomorrow. I’ll order out the carriage for you, and if you cannot get there in the carriage, you will have to go in the gig. Or you will have to ride! It surely would not hurt you to ride if the horse only walked, and the groom could even lead it to make absolutely sure that you were safe. I want you to go down there and tell them that Ralph has escaped and that he is a danger to the public safety. There is a big reward on his head, Julia! I want you to tell them that too. I want you to tell them that if he comes to Acre, I personally will give one hundred pounds to anyone who gives us warning. That should do it! Won’t it, Julia?’

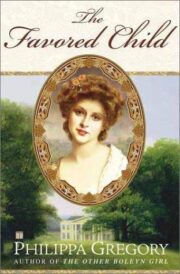

"The Favoured Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Favoured Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Favoured Child" друзьям в соцсетях.