Lord Ramsay, on the other hand, enjoyed himself hugely. Ignoring the household’s usual hours, Lord Ramsay rose whenever he wanted to, invaded the kitchen for repast when he was hungry, then packed his notebooks and pencils in a little knapsack and strode off alone into London. The majordomo tried to explain that Hart kept the carriage standing by to take Lord Ramsay wherever he wished, but Lord Ramsay ignored him and walked to the museum every day or took an omnibus. He discovered that he loved the omnibus.

“Just imagine, Eleanor,” Ramsay said when he arrived home very late the second night of their stay. “You can go anywhere you wish for a penny. And see so many people. It’s quite entertaining after the isolation of home.”

“For heaven’s sake, Father, don’t tell Hart,” Eleanor said. “He expects you to behave like a peer of the realm and travel about in luxury.”

“Whatever for? I see much more of the city this way. Do you know, someone in Covent Garden tried to pick my pocket? No one’s picked my pocket before. The thief was only a child, can you believe it? A little girl. I apologized to her for my pocket’s being so empty, and then I gave her the penny I was holding for the omnibus.”

“What on earth were you doing in Covent Garden?” Eleanor asked worriedly. “That’s nowhere near the museum.”

“I know, my dear. I took a wrong turning and wandered quite a long way. That is why I am so late getting home. I had to ask many a policeman for directions before I found the way.”

“If you took the carriage, you wouldn’t get lost,” Eleanor said, putting her arms around her father. “Or have your pockets picked. And I wouldn’t worry so.”

“Nonsense, my dear, the policemen are most helpful. You have no reason to fret about your old papa. You just get on.”

He had a gleam in his eyes, the maddening one that told Eleanor that her father knew full well what he was doing but would play the absentminded old man as much as he liked.

While her father busied himself at his museum or riding the omnibus, Eleanor worked on her ostensible duties. She found that she enjoyed typing the letters Wilfred gave her, because they allowed her a glimpse into Hart’s life, albeit his formal one.

The duke is pleased to accept the ambassador’s invitation to the garden party on Tuesday next.

Or,

The duke regrets that his attendance at the gathering on Friday night will not be possible.

Or,

His Grace thanks his lordship for the loan of the book and returns it with gratitude.

Polite nothings and very unlike Hart’s style of delivery. But Hart didn’t actually write the responses—he scrawled yes or no on letters that Wilfred vetted, and shoved them back at him. Wilfred drafted the replies, and Eleanor typed them.

Eleanor could just as soon have made up the words herself, but Wilfred, proud old soul, thought this duty was one of his raisons d’être, so Eleanor never offered to take over.

Just as well. She’d be tempted to type such things as: His Grace regrets he will be unable to attend your charity ball. Of course he won’t come, you silly cow, not after you called him a Scots turd. Yes, I heard you say that in Edinburgh last summer, and it got back to him. You really ought to guard your tongue.

No, better that Wilfred drafted the letters.

As for the photographs, Eleanor pondered what to do. Hart had said there’d been twenty photographs in all. Eleanor had been sent the one—she had no way of knowing whether the well-wisher had them all or only this one. And if only the one, where were the others? At night, alone in her bedchamber, she would take out the photograph and study it.

The pose showed Hart in perfect profile. The hand that leaned on the lip of the desk tightened all the muscles in his arm, his shoulder round and tight. Hart’s naked thighs held sinewy strength, and the head bowed in contemplation was by no means weak.

This was the Hart Eleanor had known years ago, the one she’d agreed without hesitation to marry. He’d had the body of a god, a smile that melted her heart, a sinful glint in his eyes that had been for her and her alone.

He’d always prided himself on his physique, kept fit by plenty of riding and walking, boxing, rowing, or whatever sport took his fancy at the moment. From what she’d glimpsed behind his kilt and coat, Hart had grown even more muscular and solid since this photograph. She toyed with the fantasy of snapping a photograph of him in this pose as he was now, and comparing the two.

Eleanor’s gaze finally roved to the thing for which she pretended she had no interest. In the picture, Hart’s phallus was partially hidden by his thigh, but Eleanor could see it—not erect, but full and large.

She remembered the first time she’d seen Hart bare—up in the summerhouse on Kilmorgan land, the folly that perched on a cliff with a wide view of the sea. Hart had removed his kilt last thing, his smile wicked when Eleanor realized he wore nothing under it. He’d laughed when her gaze couldn’t help but slide down his body to him erect and wanting her. She’d never seen a man unclothed before, let alone such a man.

She remembered the thump of her heart, the flush of her skin, the triumphant warmth to know that the elusive Lord Hart Mackenzie belonged to her. He’d laid Eleanor down on the blanket he’d thoughtfully packed for their outing and let her explore his body. He’d taught Eleanor all about what she liked that afternoon. He’d been right about everything.

Hart’s smile, his low laughter, the incredibly tender way he’d touched her had made her fall madly in love with him. Eleanor believed herself the most blessed of women, and she had been.

Eleanor sighed and tucked the photograph and her memories away, back into their hiding places.

She’d been living in Hart’s house three days when the second photograph came, this one hand delivered directly to her.

Chapter 3

“For you, my lady,” Hart’s perfect parlor maid said, executing a perfect curtsey.

The envelope read: Lady Eleanor Ramsay, staying at number 8, Grosvenor Square. Same printing in the same careful style, but no seal, no indication from whence the letter had originated. The envelope was stiff and heavy, and Eleanor knew what must be inside.

“Who brought this?” Eleanor asked the maid.

“The boy, my lady. The one who usually brings messages to His Grace.”

“Where is this boy now?”

“Gone, my lady. He delivers all over the square and up to Oxford Street.”

“I see. Well, thank you.”

Eleanor would have to find the boy and put him to the question. She went back upstairs, shut herself in her bedchamber, drew a chair to the window for the light, and opened the envelope.

Inside was a piece of cheap paper sold by the hundredweight at any stationery shop, and a piece of folded pasteboard. Inside the pasteboard card lay another photograph.

In this one, Hart was standing at a wide window, but what showed outside was rolling landscape, not city. His back was to the photographer, his hands on the windowsill, and again, he wore not a stitch.

A broad back replete with muscle slimmed to a backside as firm as firm could be. Hart’s arms were tight, taking his weight as he leaned on the windowsill.

The photograph was printed on stiff paper, much like a carte de visite, but without the mark of a photographer’s studio. Hart had likely had his own apparatus for taking portraits, and his former mistress, Mrs. Palmer, had taken them. Eleanor could not imagine Hart trusting such things to anyone else.

Mrs. Palmer herself had told Eleanor what sort of man Hart Mackenzie truly was. A sexual rogue. Unpredictable. Demanding. Thought it all an adventure, his adventure. The woman in the equation was simply means to his pleasure. She had not gone into detail, but what she’d hinted had been enough to shock Eleanor out of her complacency.

Mrs. Palmer had died two and a half years ago. Who, then, possessed these damning photographs, why was he or she sending them to Eleanor, and why had they waited until now? Ah, but now Hart was poised to push Gladstone out of his seat and take over the government.

The note was the same as the first. From one as wishes you well. No threats of blackmail, no promises to betray Hart, no demand for payment.

Eleanor held the letter up to the light, but she saw no sign of secret messages or clues in the thin watermark, no cleverly hidden code around the edges of the words. Nothing but the one sentence printed in pencil.

The back of the picture held no clues, and neither did the front. Eleanor fetched a magnifying glass and studied the grains of the photograph, on the off chance that someone had printed tiny messages there.

Nothing.

The enlarged view of Hart’s backside was fine, though. Eleanor studied that through the glass for a good long time.

The only way to speak to Hart alone—indeed, at all—was to ambush him. That night, Eleanor waited until her father had retired to his bedchamber, then she went to the hall outside Hart’s bedroom, one floor below hers. She dragged two chairs from the other side of the hall to the bedchamber door, one chair for Eleanor to sit on and one for her feet.

Hart’s house was larger and grander than most in Mayfair. Naturally. Many London town houses were two rooms deep and one room wide, with a staircase hall opening from the front door and running up through the entire house. Larger houses had rooms tucked behind the staircase and perhaps a second room in front of the staircase on the upper floors.

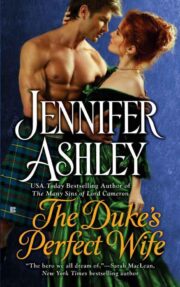

"The Duke’s Perfect Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duke’s Perfect Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.