"If you are willing to allow me to be in danger, how can they do anything else?" Allegra said quietly.

"Do you think your friends are brave enough to carry this off, or will they panic at the first sign of danger?" the duke said.

"I believe we are all brave enough, Quinton, but who among us can say for certain how brave we will be until we directly face danger? Besides, if we do this thing properly, there should be little danger to any of us. I believe that we can outsmart a couple of lackwit peasants. After all, we are English," she concluded.

He laughed. "God bless me, my darling, you suddenly sound most patriotic and grand. Very well, I shall speak to Dree and Marcus first thing in the morning. Then we shall go to the Bellinghams, and tell them only that a rescue attempt will be made. I will not tell them that you ladies are to be involved, for it would distress them, and send them both to their beds with the vapors. While I am dealing with my friends, you must explain to yours what we plan to do, and Allegra, you must give both Eunice and Caroline the opportunity to cry off if they wish to do so. And they may upon reflection. If they do, you cannot be angry. Do you promise me that?"

"They will not cry off," Allegra said with certainty. "Do you know how dull London has been for us? Parties. Museums. The Tower Zoo. Never again! At least this will afford us a little excitement before we return home to the country to do our duties, and fill our nurseries with those babies that you gentlemen seem to want." She smiled at him, and kissed him softly. "We must work very hard to have those babies, Quinton. Very hard."

He tipped her face up to his, and kissed her. "You will gain no argument from me, madame, on that point," he told her, and his hand slid beneath her fur-lined cloak to fondle her breasts.

"Ummm," she sighed contentedly, melting into his embrace. But then their carriage came to a definite stop.

"We're home," he noted, a tone of regret in his voice.

"We can continue this upstairs, if my lord wishes," she replied playfully, her little tongue licking at her lips provocatively'

"I must pen notes off to Dree and Marcus, but I will join you shortly, mon coeur," the duke whispered against her lips.

A footman opened the coach door and offered a hand to the duchess who descended and hurried into the house, going directly up the staircase to her apartments. She entered to catch Honor and the duke's valet, Hawkins, in a torrid embrace. They broke apart guiltily and red-faced, as she stepped through the doors.

"M'lady!" Honor squeaked. Her bodice was quite awry.

"If you seduce my maid and put her in the family way, Hawkins," Allegra said, "you must be prepared to make an honest woman of her."

"Yes, my lady," the valet said nervously.

"And you are prepared to do so? No wife, or dear friend tucked away in another place here in London, or down at Hunter's Lair?" Allegra persisted. "Honor, for goodness' sake, straighten your bodice."

"No wife, or friend, my lady," the valet said, shuffling his feet.

"Very good, Hawkins," the Duchess of Sedgwick told her husband's valet. "You are dismissed. Go and be ready to help your master to bed. He will be up shortly." Allegra turned to Honor, who was lacing her gown front. "And I am ready for my bed, Honor. Come and help me." She turned and moved from her salon into her bedchamber.

"Whew!" Hawkins breathed softly as Allegra disappeared into the other room. "She's a proper cool one."

"Haven't I taught you better yet about speaking rude against my lady?" Honor scolded him.

"Guess I need more lessons," the valet said with a wink, and then he was gone out the door, and to his master's room.

With a smile Honor hurried to her mistress's aid. "You ain't mad at me, are you?" she asked.

"Just be careful," Allegra said quietly. "I'm not certain that I trust Hawkins where you are concerned, Honor. I love you too dearly to allow him to harm you in any way."

"He's more bark than bite, my lady," Honor answered her mistress, "and he surely ain't as smart as I am," she chuckled. "If he means to find himself by my side in bed, he'll have visited the parson with me first. A kiss and a cuddle don't make babies. Of that much I'm certain."

Allegra laughed. "I shouldn't have worried," she replied.

"I'm glad you do," her maid responded. She knelt, and pulled her mistress's little slippers off. "Lord, my lady, your poor wee feet are as cold as ice. These little slippers may be fashionable, but they ain't meant for the cold streets of London."

"Honor, I need your help," Allegra said quietly. "I know I don't have the right to ask this of you. You are free to tell me so, and I shall still love you. Do you remember when I was a little girl and you would sit with me when James Lucian and I had lessons:1 And how one day when we were doing a French exercise you corrected us and we were so surprised? It was then we discovered that you had learned the language right along with us and could speak it beautifully."

"I remember, my lady," Honor said.

"Do you think you could speak it again? I mean, given a bit of practice?" Allegra wondered.

"I wouldn't know until I tried it, my lady," Honor said honestly.

"Comment vous appelez-vous, mademoiselle?" Allegra responded.

"]e m'appelle Mademoiselle Honneur," the maid replied.

"Quel age avez-vous?"

"J'ai vingt-quatre ans, madame," was the answer.

"You do remember!" Allegra cried.

"Guess I do," Honor said, sounding surprised.

"Then let me tell you what we are going to do," Allegra said, and she explained the situation with the Bellinghams' niece, the Comtesse d'Aumont, and how they were going to France to rescue her. "If you are willing to come with us it would help tremendously," Allegra said. "I need it to look as if the local committee of safety sent a leader and enough citizens to bring the countess and her children to justice. And you speak French well."

"Can the other ladies?" Honor asked.

Allegra nodded.

"I'll go," the maidservant told her mistress. "It's an adventure, and one day if I have grandchildren, I'll tell 'em how their old gran helped save three innocent lives."

"Bless you, Honor," Allegra said wholeheartedly. And then she added, "but let me tell his lordship. I have only just convinced him that this is the right thing to do."

"Men don't have a whole lot of common sense, m'lady," Honor replied. "I think that's why God created us womenfolk. Men surely need someone to tell 'em what's right, and what ain't."

Allegra giggled. "Oh, yes, Honor," she said. "How absolutely correct you are!"

Chapter 14

Frederick Bellingham looked at the three young men standing before him. "Are you certain you want to do this?" he asked for at least the third time. "It is dangerous, but she is my brother's daughter. I must get her safely to England. Yet do I have the right to put you three in danger?" Past sixty, Lord Bellingham looked weary with his worry.

"We have discussed it carefully, my lord, and we are willing to help you. The plan is formulated, but I shall not burden you with the details. You, however, must tell me where your niece and her children live. How far from the coast are they?"

"The village of St. Jean Baptiste is located but eight miles from the town of Harfleur, which as you know is directly on the sea," Lord Bellingham told them. "My niece's home is nothing more than a large gray stone house. The family's small wealth comes from their flocks of sheep and their apple orchards. It's a most modest establishment."

"A perfect little estate for someone now in a position of power to confiscate for himself," the Earl of Aston remarked. "A helpless young widow and her children. The fellow, whoever he is, is a proper villain, I fear."

"And you are certain your niece is willing to give up her home under the circumstances?" the duke asked. "Her missive to you has said so? She will come to England?"

"She writes that she has been foolish, and should have put her son's estate with a trusted friend, and then come to England until order is restored in France. She never expected that anyone would bother them, for they are neither rich nor powerful. They are just simple country folk," Lord Bellingham said, sighing again. "What kind of a monster would prey on a woman and her children? The Comte d'Aumont was a good man. A hero of reform!"

"More ordinary folk have died in this revolution," Lord Walworth noted. "That dressmaker who does for our wives, Madame Paul. She lost family to the guillotine. What harm could a dressmaker's family have possibly caused to have required such a sentence as death?"

"I will give you a letter to carry to Anne-Marie," Lord Bellingham said to the duke. "That way she will not be afraid."

"Does she speak English?" the duke asked the older man.

"I have no idea," he replied. "We always spoke French to her on the rare occasions that we saw one another. She writes to us in French," he noted.

"Probably don't speak the king's langue," the earl remarked. "You'll have to do all the talking, Quint."

The duke nodded, and then he said to Lord Bellingham, "We will go tomorrow, sir. We will inform you when we return."

The two men shook hands.

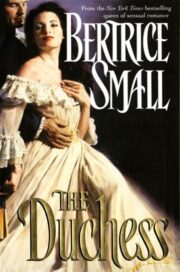

"The Duchess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duchess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duchess" друзьям в соцсетях.