The weather was so cold that even the duke would not ride outside, but remained within the coach with his wife. His vehicle was followed by a second carriage in which Honor, and the duke's valet, Hawkins, rode with the rest of the luggage. This auxiliary vehicle had but one driver, the second undercoachman. It would be his duty in London to oversee the stables and ducal transport while they were there.

While cold, the weather held, though it was gray and cloudy. They stopped for luncheon, and then for dinner and lodging at inns that were expecting them. They did not have to change horses because the animals were well cared for, and well rested each night. Allegra was very grateful for the hooded beaver-lined velvet cape her husband had given her for Christmas. She unashamedly wore several flannel petticoats beneath her skirt. This was no time to be fashionable, and besides, who was to know, she thought, as she snuggled into the dark green velvet of the fur-lined and -trimmed cape.

It took them several days to reach London, but when they did, the servants hurried from Morgan House to help them out of their coach and escort them into the house. Marker, the family butler, came forward, bowing, a smile upon his face.

"Welcome home, Your Grace," he said. "Your father is here, and will see you and His Grace in the library when you are settled."

"Papa! Ohh, let us go now," Allegra said, unfastening her voluminous cape and handing it off to a footman.

"Very well, my dear," the duke agreed. He hadn't thought his father-in-law would be here, but then why wouldn't he? It was his house, and he certainly always had business in London.

Septimius Morgan arose from his chair by the fire to greet his only child and her husband. "I shall not be with you long," he reassured them with a smile. "I am anxious to return home as soon as possible. Your stepmother hasn't felt well of late."

"What is the matter?" Allegra cried, a worried expression crossing her beautiful face.

"Nothing more, my child, than a winter ague," her father assured her with a smile. "How it pleases me that you love Olympia as I do." He indicated a settee opposite his chair, and the couple both sat. "How long do you plan to remain in town?" Lord Morgan inquired as he seated himself.

"Only a few weeks," the duke replied. "Our friends, Aston and Walworth, are also here with their wives. We plan to make a time of it, Septimius. We shall visit the opera, the theatre, perhaps even Vauxhall if there is something of note to see. I should also like to go to Tattersall's. While I have an excellent stud, I could use some good blooded mares to improve my stock. We will certainly be gone before The Season begins."

"Do you intend to take your place in the house, Quinton?" his father-in-law asked him.

"Yes, I think I should like to see what is going on right now," the duke answered.

"I have never asked you this," Lord Morgan said, "but are you a Tory, or a Whig?"

"I think I am a little of each, sir, which is why I do not visit Parliament too often," the duke responded with a small smile. "Nothing in this life is only black or white, Septimius. I cannot become enthusiastic over a political party and cleave only to it. Politics are made up of men, and men, I have learned, are quite fallible."

Now it was Lord Morgan's turn to smile. "You have married a wise man, my child," he told Allegra.

"And you, sir," the duke said. "Are you fish, or fowl?"

"Like you, Quinton, neither. A man in trade such as myself, even with a Lord before his name, cannot afford to take sides. I leave that to cleverer heads than mine, and those whose passions run higher."

The duke chuckled, and turned to his wife. "You have a devious and clever father, my darling."

"As long as the country is well run," Lord Morgan said, "I am content." He looked closely at his daughter, and what he saw pleased him greatly. Sirena had written that Allegra had fallen in love with her husband, who was already in love with her, but now that he saw it with his own eyes, he was happier. They had only been at Hunter's Lair overnight for his daughter's birthday, and he had had no real chance to observe the pair. Olympia would be delighted, for it was really she who had engineered the match with Lady Bellingham's aid.

"When will you leave us, Papa?" Allegra asked him.

"In two or three days, my child, but I am leaving Charles Trent behind to oversee my business. He will be a shadow, of course, but should you entertain, he will be an excellent extra gentleman for the table. He has offered to tuck in at my offices, but I said you would not hear of it."

"No, no," Allegra agreed. "He must remain here in his own rooms."

The next morning while her father and husband had gone off to the House of Lords, Allegra sat down with Charles Trent. "It will be expected that I give an at home," she said. "How long will it take to arrange the invitations? I assume you know to whom my cards should be sent? We do not intend to remain in London long, but I know that as the Duchess of Sedgwick I cannot come and not have an at home."

"The invitations are already engraved, Your Grace," Mr. Trent answered her. "It only remains for you to choose the day. Might I suggest the last day of February?"

"We intend leaving shortly afterward," Allegra said thoughtfully. "How ridiculous that we must give people a month's notice. Sirena and I went to several at homes last season. What a silly custom. You push into a huge crush of people, remain only fifteen minutes, and then leave. There is no food, no drink, no entertainment at all. And your levee is not considered a success at all unless at least one woman faints dead away, and the crowds are overwhelming. I do not see the point of it all. Still, it is the fashionable thing to do, and so I must. I would not want the gossips saying I was not worthy of my husband's name and title."

"I am inclined to agree with Your Grace on both counts," Mr. Trent said with a small smile. "It is ridiculous, but the gossips will indeed cry you are ill-bred if you do not do it. Shall we say the last day of February?"

"No, make it the twentieth, if it is not a Sunday," Allegra said. "Then at least we will have a pleasant final week in town."

"Very good, Your Grace," Mr. Trent answered.

"How odd to hear you call me that instead of Miss Allegra," she replied. "I am still not used to such grandeur, although here in London I suppose I must play the role to the hilt."

"Indeed you must," he advised her. "Wealth and position mean a great deal to most of the people with whom you will have to associate while you are in town, Your Grace. In one short season you have climbed from the bottom of the tree to the top of the tree. There will be many who still resent it, completely overlooking the fact that it is your wealth, and the duke's family, that have made you such a perfect match. You do, however, have an excellent friend in Lady Bellingham."

"Is she in town yet, Mr. Trent?"

"I believe she arrived with her husband several days ago."

"Please send her an invitation to tea tomorrow," Allegra instructed her father's personal secretary.

"Of course, Your Grace," Mr. Trent replied.

The duke and Lord Morgan returned from Parliament's opening late in the afternoon. Allegra had tea served in the smaller green drawing room. Marker set the large silver tray on a table before the young duchess, and then stepped back politely. Allegra poured the fragrant India tea into French Sèvres cups for her husband and her father, while a footman passed around the crystal plates holding bread and butter, and small cakes filled with fruit that had been iced with a white sugar icing.

"Was it interesting?" she asked the two men.

"There is a small visitors' gallery," her father said. "Any day that you and your friends would like to visit, I shall arrange it. Depending on what they choose to argue about makes it interesting, or else deadly dull. Today the king opened the session, and while colorful, it is usually quite boring. I must say the day lived up to its promise, eh, Quinton?" he finished, his eyes twinkling as he looked at his son-in-law.

"Indeed," the duke replied. "The Whigs are out of power right now, and seem to become more radical with each passing day. All they can talk about is reform, reform, reform. That usually involves taking from those who work hard, and giving it to those who do not. Since many of the more prominent Whigs are wealthy men, you can be certain they will not penalize themselves."

"But there is much poverty, especially here in the city," Allegra said. "I have seen it myself."

"You can be sure the government will do only what they are forced into to care for the poor," her father said dryly.

"But what about the Tories?" Allegra asked.

"They are more conservative," the duke replied. "They have, since their inception in the sixteen hundreds, favored the Stuarts, and opposed any attempts to deny our Roman Catholic citizens their rights. When King James II was overthrown in what the historians like to call the Glorious Revolution, and his daughter Mary came to England to rule with her Dutch husband, the Tories favored the Jacobite cause. But they were not averse to the Hanoverian succession after Queen Anne died. The Whigs, however, used the Tories' former Jacobite leanings against them. Tories were very neatly excluded from government by the first two Georges. The current Prime Minister, Mr. Pitt the younger, has changed all of that," the duke said.

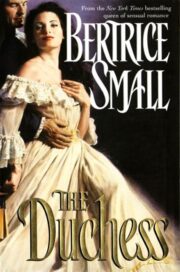

"The Duchess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duchess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duchess" друзьям в соцсетях.