"But I do want to marry Quinton," Allegra told him.

"Do you love him?" Rupert queried her. "Does he love you?"

"Of course we do not love each other." Allegra laughed. "We haven't known each other long enough to even know if we really like each other, but I think that we do. We get on very well."

"But I love you, Allegra!" Rupert cried. "I have loved you ever since we were children. Even if you did not love me, I should love you. A woman should be loved."

"Rupert, I can never think of you as a husband. You have been my brother, my best friend next to Sirena," Allegra responded. "Now stop being so foolish. My wedding date is set for October fifth in London at St. George's. The king, the queen, and Prinny are coming. Lady Bellingham says it will be the wedding of the year. Madame Paul has already begun making my wedding gown. It is to be white and silver. Quite fashionable, I am told," she finished with a smile.

"You are so young," he replied. "You cannot know what you want. You do not see past the excitement and the glamour of it all. You have never even been kissed!"

"Of course I've been kissed," Allegra snapped, now becoming irritated by this cow-eyed young man. "The duke and I have kissed many times. I quite like it, Rupert."

He suddenly stood, pulling her up with him. Then he kissed her. His mouth mashed against her; his tongue tried to push into her mouth; and he smelled of onions. "Allegra, Allegra, I love you! Marry me, my darling girl. I realize a country churchman's life cannot match the excitement of a duke's, but I adore you. Tell me you will send this duke packing, and be mine."

Allegra struggled from his embrace. She smacked him hard upon his cheek. "How dare you, Rupert Tanner? I was almost ready to forgive you for telling the duke that you and I had an informal agreement; but now I shall not. I am marrying Quinton Hunter because I want to marry him. No one is forcing me to it. It is my duty as my father's daughter to make the best marriage possible. As Papa's heiress a duke is just the right husband for me. Now go away. I do not want to see you again!"

"London has not been good for you, Allegra. You have grown hard," he accused her.

"Oh, Rupert, do not be such a dunderhead," Allegra told him. "My papa loved my mother, and what did love bring him? Scandal, embarrassment, and heartbreak. Quintan's antecedents all married for love. What did it bring them? Poverty, and the loss of much of what his family once had. The betrothal between the Duke of Sedgwick and myself is based upon sound principles. He has the pedigree, and I have the fortune. It is a perfect match. One made in heaven, you might say," she concluded with a small chuckle. "Go home. Find a nice young woman who will make a good clergyman's wife. One who will enjoy teaching the children their Bible stories, and ministering to the sick. I certainly shouldn't. Lord Stoneleigh's daughter, Georgianne, is moonstruck over you. In another year she'll be out of the schoolroom, and ready to marry. You really should ask for her before someone else does. Papa says she has a small, but respectable dowry."

"What has happened to you, Allegra?" he said.

"I have grown up, Rupert, but even before I did, I never said I would marry you, or that I desired to be a clergyman's wife with all the onerous duties it entails. You and I spoke about marrying so I might escape my London season. It was a childish fantasy, and Papa wisely saw that. I don't care for you except as a brother. I surely never will. In fact I shall never love anyone. Love only brings a host of problems I should rather not deal with, Rupert. Now, please go home. I don't want to see you again. Perhaps after I am married, and come to visit at Morgan Court, I may forgive you your behavior this evening, but not now." She stood stonily as he turned abruptly and departed the pavilion.

Allegra sat back down. Rupert had kissed her, and she hadn't liked it one bit. And he had pushed his tongue at her! Quinton had never done such a thing until she had become used to his kisses. Then she laughed to herself as she remembered asking Quinton if he was good at kissing. Well now she knew. He most certainly was good. Very good!

Madame Paul arrived two days later from London ready to fit Allegra's wedding gown. She brought with her a number of fabric samples from which Allegra would choose so Madame could make up a trousseau of gowns for the future duchess. She was full of the latest gossip she had received from France. The little king, Louis XVII, had survived his murdered parents by two years, dying in his prison on the eighth of June, in Paris.

"Some say he isn't dead, that the child in the Temple was an imposter," Madame told Allegra, "but those savages would never allow a Bourbon to escape their vigilance. The king is dead, poor child. Did I not hear that your brother was also a victim of the revolution, Miss Morgan? It was when Monsieur Danton took over the royal power in the autumn three years ago. That was when I escaped. It was a bloodbath, I tell you! No mercy was shown. Priests, artisans, people like me who did business with the well-to-do. Who else, I ask you, Miss Morgan, could afford a Madame Paul gown but an aristocrat? And plenty of them died. It was horrible. Little children in their satin gowns and suits guillotined before their parents' eyes. It was terrible! Terrible!"

"Yes," Allegra said tightly. "That was when my brother was murdered." She felt faint, but reaching out she steadied herself, her hand gripping the back of a chair.

"Ahh, Miss Morgan, I have upset you," Madame said, genuinely distressed. "I did not mean to do it. I have tried to put it all behind me, but the news of the young king has brought it all back to me once again." Reaching for her lawn handkerchief she dabbed at her eyes.

"It is all right, Madame Paul," Allegra told the modiste. "You have suffered, too, losing your sister, and having to leave your homeland. We don't even know where my brother's body was interred. There are no niceties in a revolution, are there?"

"No, there are not," the older woman agreed. She did not increase Allegra's sorrow further by explaining to her that the bodies of the slaughtered in Paris, and elsewhere in France, were tossed helter-skelter into open pits. The baskets of heads were dumped atop them, and then lime was poured on the carnage before it was covered with dirt. There were no markers, and by the following year the mass graves were invisible, covered by weeds and wildflowers.

Allegra was measured for her glorious wedding gown. It would, along with Allegra's new wardrobe, be delivered to the Berkley Square house at the appropriate time.

"For you, Miss Morgan, I have turned away at least half a dozen important clients," Madame Paul told Allegra.

"Gracious," the younger woman exclaimed, "why would you do such a foolish thing, madame?"

"My shop is small, and I have but Francine and two seamstresses," came the reply. "I must weigh and balance who I will accept as a client. Your papa is the richest man in England, and your husband-to-be is a duke. Then, too, there is the fact that you pay your bills on time."

Allegra thought for a long moment, and then she said to the Frenchwoman, "Could you use an investor, madame?"

"An investor?" Madame cocked her head to one side.

"Yes, an investor. Someone who would finance a larger shop, and more staff for you. In return you would render a portion of your profits. It seems a shame that you cannot increase your business when everyone knows you are the finest dressmaker in London. You could still remain exclusive while turning a neat profit," Allegra said.

"Turn a bit for me, Miss Morgan," Madame Paul said. "You could arrange for your papa to invest in my business?"

"Not Papa," was the reply. "Me. My father will tell you I am quite astute at picking my investments."

"And what kind of a return would you expect on such an investment, Miss Morgan?" Madame asked despite the fact her mouth was full of pins.

"I should want thirty percent of your business," Allegra said.

"Sacrebleu, mademoiselle! C'est impossible! C'est fou!" the Frenchwoman cried. Then her eyes narrowed, and she said, "Fifteen percent, mademoiselle."

"Madame, I will not haggle with you," Allegra answered her. "I am young, but I am no fool. Twenty-five percent, and I will accept nothing less. Think, Madame Paul! A man would not put his monies in a dress shop. Only a woman would, and who among the ladies of the ten thousand would make you such an offer as I. I will not tell you how to run your business, or what clients to take, or what fabrics to purchase. I will be a silent partner, contributing only the monies you need to succeed. In return I will receive twenty-five percent of the profits, and Madame Paul, there will be profits."

"You may step down, Miss Morgan, I have finished," the dressmaker said, and then she added, "you drive a hard bargain, but I agree."

"And Mr. Trent will oversee the books," Allegra added.

"Miss Morgan!" The Frenchwoman looked outraged.

Allegra laughed. "Why should you have to bother with the business of your business, madame? You are an artiste."

Now it was Madame Paul who laughed. "And you are a very clever young lady," she replied.

"Where will you go on your wedding trip?" Madame Paul asked Allegra. "Portugal and Italy are beautiful, I am told."

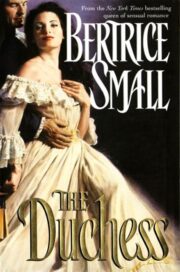

"The Duchess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Duchess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Duchess" друзьям в соцсетях.