All that I wanted, however, was to follow him around. It was ironic that, after hiding from him for so long out of fear, here I tagged along after him, never letting him out of my sights. He was my protector and could keep my bad dreams at bay. That didn’t mean I wasn’t still a little afraid of him; I was only too aware that he was capable of turning on a dime. But here, on this island, he seemed in control and—dare I say it?—at peace. He was a rock, under which I could take refuge.

We spent most of our days together. For Adair, there was no television or idle surfing on the computer. It turned out that he read constantly. He’d stored all the books he never read, poetry and literature, on the highest shelves in his study but pulled them down to read to me, translating from the original French, Italian, or Russian. When he tired of reading aloud, he read to himself, studying whatever had caught his fancy, while I lounged nearby like a companionable cat. Rather than feel as though I were imprisoned in a small space for hours on end, I came to enjoy it. The wind howled outside the window, but Adair kept the fire built up, and so I felt snug and cozy. There were two stout armchairs beside the fireplace in which to relax and a window seat, tucked between two bookcases and outfitted with a deep box cushion, covered with an old kilim. Pillows and rustic blankets were piled in corners. It reminded me a little of Adair’s old boudoir in the Boston mansion. All it needed was a hookah.

We managed to have quite a bit of privacy, as Robin and Terry were used to Adair keeping to himself during the day. God only knows what they were up to, wherever they were in the fortress. At first they checked up on us regularly, knocking on the door to see if we wanted to join them for tea or lunch, secretly looking for signs of growing intimacy between Adair and me. They couldn’t force themselves on us, however, and Adair never invited them to join us, and so after each innocent inquiry the girls had no choice but to leave us alone.

Between books, we’d talk. Not about whether there was the chance of a future for us—no, nothing as weighty and frightening as that, as much as it had to be in both of our thoughts. Conversation started tentatively, as we figured out where the land mines lay. There was so much history between us, after all, so much that was too sensitive to discuss so soon. Once we’d started, though, conversation came easily. We reminisced about life in the old days, how hard everything was before electricity and plumbing, motorcars and airplanes. Adair had a wealth of stories; he’d lived for such a long time and had experienced things I knew only from books. He could be funny; he could be thoughtful. He could even be philosophical.

And, for the first time, he acknowledged remorse for things he’d done. This was quite a shock, though I tried not to show it on my face, for in the past Adair had never expressed regret of any kind. He’d always had reasons for his actions—whether moral or just in the eyes of other people, it didn’t matter to him—and once he’d embarked on a course, he rarely let doubt stop him but, rather, swatted it out of his path without so much as a backward glance. This was a fundamental change in his nature, and as I listened, I felt a creeping sense of relief and optimism that perhaps there was hope for him yet. That, given enough time, the leopard could evolve and change its spots: anyone could change, even Adair.

Being together like this reminded me of our time in Boston, when I had been part of his strange household, one of five people to whom he’d given eternal life in exchange for blind obedience and service. I asked Adair whether he had been in touch with the others and he admitted that he avoided Alejandro, Tilde, Dona, and Jude. “I can’t abide their company anymore,” he confessed, saddened. “There was a time when I needed them to be a buffer between me and the rest of the world. They served a purpose, but that time has passed. I’d rather live simply and privately.”

I thought about inquiring after my dear old friend Savva. He, too, had been one of Adair’s companions once, and we’d spent a lot of time together when I was on the run from Adair. Savva had fallen very far from the brilliant, irascible, and maddening young Russian I’d known a hundred years earlier. He had turned to narcotics for respite from his demons and become a bad heroin addict. He’d driven away all his friends and could no longer cope with the ever more complex demands of modern life. Savva was living proof that eternal life was not a gift to everyone—for the very unstable, it could be a never-ending hell. When Adair and I had last parted, I’d asked him to show mercy and release Savva. Now, I couldn’t bring myself to find out if Adair had done as I’d asked.

No, I wouldn’t ask about Savva. Since I’d come to the island, I’d seen many promising signs that Adair had truly changed; it gave me hope. If only every day could be like this: the two of us lying together in the sun, enjoying each other’s company.

A dangerous and seductive thought had begun to take root in my mind: I started to think how nice it might be to stay right where I was. After all, I had nowhere else to go and no one waiting for me. I could put off the lonely job of building a new life—which, frankly, got more tedious and seemed more pointless each time I had to create a new identity. If I could put out of my head all the bad things that had happened between Adair and me, if I could pretend that there was only the here and now, then I might be able to manage it. I could live with Adair day to day, never needing to look ahead, never daring to look back.

I knew that if I asked, he would make it happen. He would send the girls away so I could take refuge in his bed, where the nightmares would never dare to follow me. And what waited for me in his bed but days and nights of stupendous sex? Sex so pure and powerful that it would keep me focused on the moment, on the physical pleasure of the body, and free me from my overburdened mind. More than any man I’d ever known, Adair had the ability to turn sex into both a physical and spiritual act. We would stay in the bedroom for days at a time, feasting on each other, right down to our souls. I ached to give myself up to Adair like this. It would make life so much simpler. . . . As long as I remained in that state, as long as I could stay drugged up on pure experience, it could work. It would be like being drunk and never sobering up. It was very tempting to consider and if I’d been just a little bit weaker, or more selfish, I might’ve let it happen.

But then I remembered all the terrible things we’d done, Adair and I, and I knew we wouldn’t be so lucky. Fate would not let us be happy, not truly, not when so much remained unaccounted for. My sins were slight—minor deceptions, a white lie told here or there—compared to Adair’s, which ran past duplicity and theft, all the way to murder. Fate could not possibly be finished with the two of us. Besides, I didn’t come here looking to escape. There was something I had to do, and I would never find peace until I followed through with it.

FIVE

I was playing solitaire with a worn, old deck of cards I’d found in a desk drawer, while Adair read, reclining on a bower of pillows on the floor. He broke from his reading to roll onto his back and cock his head in my direction, as though he was about to speak. I don’t think he was aware of how very appealing he appeared at that moment, his hair loose and leonine, the first few buttons on his shirt undone to give me a peek at his chest, and his jeans twisted so they were tight across his hips. He’d thrown an arm over his face to shield his eyes against the sun, but I could still see the lower half of his face, including his strong mouth, and I recalled how kissable it was. The sight of him was tempting.

Where’s the harm in a cuddle? I thought, even though I knew we probably would not stop there. And if we were to indulge this once . . . if I leaned over him for a kiss and took the opportunity to press full against his chest . . . if I reached down to undo the fly of his jeans, and unleash the passion that I knew was inside him . . . would I be lost to him for good? Could we stop again after having done the deed once?

But why not try it and see? a voice in my head asked. After all you’ve been through the past year, nursing your dying lover, it is time for you to be reborn. And you know this man; you’ve been in his bed a thousand times already. Stop thinking and do something about it. Go over and kiss him. Tell him you want him to take you right here, now. Tell him that you want him inside you, like the old days. Where is the harm?

I was about to abandon my cards and slither over to him when he said unexpectedly, “There’s been something I’ve been meaning to talk to you about.”

“Oh?” I said, already half risen to my feet.

“It has to do with the girls.”

Ah yes, the two women who had fallen for Adair and were sharing his bed. I had somehow forgotten about them in the heat of the moment. There was the harm in succumbing to temptation: it would be an entirely impetuous and selfish act with consequences that would harm them. A chill settled over me. It would be irresponsible to just do as we pleased. We both had responsibilities, after all: he, the girls; and me, rescuing Jonathan.

He sat up and leaned forward, his forearms resting on his knees, oblivious to the thoughts I was battling. “It’s hard to explain, but ever since Robin and Terry arrived, I’ve had the feeling that something—strange—is going on. I’ve had no one to discuss it with, but now you’re here, I thought . . .” He shook his head, impatient with himself.

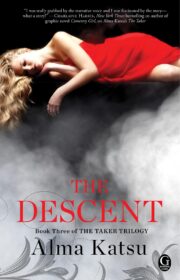

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.