Some would say I should never have returned to Luke if this was how I felt about Adair, that it was wrong of me to go back to him if I had any doubts. But complete fidelity of the heart in a relationship is something that has always eluded me. I have often wondered how these people manage to live such straightforward lives, to keep their emotions so simple and tidy. Do they weed out life’s complications as ruthlessly as they would weed a garden? Sometimes a weed turns into a beautiful flower or a helpful herb but you’ll never know if you pull it too soon. Do they ever allow themselves regret for the things they’ve thrown away? I would ask these self-assured people which of us has the luxury of an iron-clad guarantee? Who can be 100 percent sure of one’s choices in life? How do you know that your beloved will always remain the same, or that you’ll never change your mind? Growth and change are two of the great gifts we get from time. It would be shortsighted to spurn them.

Besides, I did love Luke—I did. But he wasn’t the only one I wanted, and wanting isn’t the same as loving. Just as I knew I loved Luke, I wasn’t sure whether I loved Adair. I couldn’t rule out that my attraction to him wasn’t an advanced case of lust, though that’s not to say it was inconsequential. Only a fool would underestimate the power of lust. Kingdoms have been won and lost, men and beasts have battled to the death over it.

Now, if I had been the same girl I’d been at the start of my adventures—the same girl who had loved Jonathan so blindly—I know what choice I would’ve made. I would’ve tossed aside a good man like Luke to take my chances with Adair. And I would’ve been miserable before long, held hostage by Adair’s precipitous temper and erratic behavior, which in my inexperience I would’ve accepted without so much as a whimper. I hadn’t yet learned that it was okay to make demands of the people we love, that we didn’t have to accept others exactly as they came to us. No one is perfect, after all.

As soon as I quieted these voices chasing each other in my head, I crept toward Luke, lying in bed. I felt queasy and anxious. God help me, I didn’t want to be back in that room. I was glad to have comforted Luke when he was dying, but I didn’t want to relive the experience, not so soon after it had happened. I should’ve been happy for this chance to see Luke again, but I wasn’t.

An oxygen line ran under his nose. His wrists were so bony that his identification bracelets hung from them like paper manacles. His bed was set at a forty-five degree slant to help with nausea, but it made his head hang forward at a frightening angle, as though his neck had been snapped. On second thought, he didn’t look as terrible as he could’ve; whatever power had brought Luke and me together at this moment, it had been kind enough to make Luke look healthy, not as wasted by illness and exhaustion as he’d been the last time I saw him. He even had his hair, those unruly sandy brown curls. I was thinking how much I’d like to smooth his hair back from his face—just for the excuse of touching him—when his eyes suddenly opened.

“Lanny,” he said, recognition in his gaze. So he could see me, too, as Sophia had. “Is that you?”

“Of course it’s me.” I smiled and reached for his cheek, brushing it gently. It felt solid enough.

“Am I dreaming? Your voice . . . it sounds like you’re right next to me.”

“That’s because I am here, Luke. This isn’t a dream. You can trust your eyes.”

We hugged. I couldn’t bring myself to kiss him, however, and we hung in an awkward embrace. We still had tenderness, but the passion between us was gone . . . unsurprising at the end of a long and intense illness. Worn out by exhaustion and fear, we naturally became numb to physical passion. After seeing Luke ravaged by drugs and madness, I could no more bring myself to feel attraction than he could have mustered the energy to respond.

Lying in his hospital bed now, he didn’t look all that relieved to see me; he seemed preoccupied and not entirely himself. “Where am I? What are we doing back in the hospital?” he asked, alarmed, looking at the tangle of tubes and wires hanging from his arms. “And what are you doing here?” His face drained. “You haven’t died, have you, Lanny? How is that possible?”

“No,” I rushed to assure him.

“Thank God.” That calmed him a bit, though he was still on edge, his gaze darting around the hospital room. “I don’t understand, though, why I’m back here. . . . Why are you back here? What’s going on?”

“I think maybe you and I have been brought together in order to talk,” I said slowly, trying to make sense of our circumstances. “Was there something you wanted to say to me? Something you didn’t tell me when we were together? Maybe it will come to you if you relax,” I said, taking his hand. “How are you?”

He gave me a sideways look. “You mean how am I since I died? How do you think I’ve been? Dying wasn’t at all how I expected it to be. Not that I was looking for a scene from the Bible, pearly gates and Saint Peter, any of that nonsense. But it was a little underwhelming. I had to figure everything out for myself when I got here—I don’t know, I guess I expected it to be better organized. . . . It’s not like the first day on a new job, there’s no woman with a clipboard from human resources welcoming you on board, no printed checklist to help you get settled in. No one tells you what to do or where to go. It just happens, whether you want it to or not.”

“What do you mean, ‘it just happens’?” I asked, not quite following him. “What just happens?”

“The next part. The hereafter. Eternity.” Oddly, he was still wearing eyeglasses, and he pushed them up the bridge of his nose as I’d seen him do a thousand times in life. He shook his shaggy head. “Whatever comes next, it’s already happening. I’m losing a bit of myself every day. My memories are fading. I don’t know how else to describe it. It’s like I’m breaking up and parts of me are drifting away or falling off.”

He sounded so sad and desperate that, even though the prospect was terrifying, I tried to remain upbeat and cheer him up. “Well, that doesn’t seem so bad. Maybe it’s all part of becoming a new person, clearing out the old, making room for the new.”

Luke looked at me as though I’d gone crazy. “What do you mean, it doesn’t sound bad? It’s the worst thing that could happen. I’m breaking apart. I’m ceasing to be. I suppose it means the very last bits of my consciousness are finally coming apart and all that was left of me—residual energy—is returning to wherever we come from.”

He was a doctor, a man of science, so I tried to appeal to his analytical side. “If your energy is returning to the cosmos, maybe that means your consciousness is going there, too. Maybe you’re about to experience the wonders of space.”

The prospect seemed to depress him further. “I don’t think so. I think it’s all just coming undone, like a tape being demagnetized. As time goes on, I remember less and less. I feel less and less. Sure, it all sounds interesting in the abstract, but now that it’s here, I’m frightened, Lanny,” he said. I’d never heard him sound as scared, not even when he confronted Adair four years earlier. “This isn’t what I expected. All those times I’d wondered what it would really be like, to be dead . . . especially after having patients die on you, being right there with them when it happened. I wasn’t prepared for this. It’s really going to be over. This is what it means to die. I’ve come to the end. I can’t believe it. It’s really going to be over.”

He was right: this was frightening, much more frightening than the many deathbed vigils over which I’d presided. I was scared for him, and what’s more, I could do nothing about it. I couldn’t stop what was happening to him, I couldn’t save him. As I contemplated all this, holding back tears, he snapped his head up as though he was seeing me for the first time since we’d materialized in the hospital room.

“You never did tell me . . . if you’re not dead, what are you doing here?” he asked. I suppose he was suspicious, and why shouldn’t he be? I was alive in the land of the dead.

I squirmed, suddenly realizing that he might be thinking that I’d come for him, that my presence here was all about him. That maybe I’d had second thoughts about his delirious request—you could ask Adair to make me immortal. I answered him truthfully. “I asked Adair to send me. I came to look for Jonathan,” I confessed, trying to look as contrite as possible.

An exasperated sigh escaped from Luke and he folded his arms, awkwardly for all the wires and needles. “I should’ve known. I should’ve guessed that. It’s always been that way with you, always Jonathan or Adair. Never Luke. Never any room for me.”

It was unlike Luke to be so candid. Staring oblivion in the face probably had something to do with it; no reason to pretend anymore. Still, I was hurt and not above rebuking him. “How can you say that? I was good to you, Luke. Especially at the end. I promised I would take care of you and I did.” We’d had a bargain. Four years ago, Luke had helped me escape from the police after I’d released Jonathan from his immortal bond, and in exchange I promised that he would never be alone. I would be his companion for life. I didn’t realize until later that I must’ve made this offer to Luke because being alone was what I feared most. He’d taken me up on my offer, nonetheless. Maybe we’re all afraid to be alone.

Here I was making good on my end of the bargain, but in a way I could never have imagined.

He seemed somewhat mollified. He looked up at me, over the rims of his eyeglasses. “I’ll give you that. But—we can be honest with each other now, can’t we, Lanny? Now that the end is near? Because I do have something I want to tell you.” He paused and looked at me tentatively before proceeding cautiously: “If you want to know how I really feel about us . . . I feel like we never should have gotten involved. I always felt as though you never really loved me.”

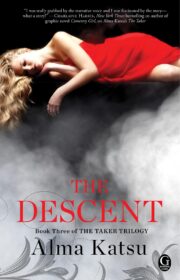

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.