“That’s ridiculous. Jonathan left with me of his own free will,” I said even though this was not strictly true. He’d been unconscious, going through the transformation, when we’d fled from town.

“That’s what your family’s supporters said, and the nonsense died down. The damage was done, however. The St. Andrews were left with no one to run the business, the sisters like ninnies and Benjamin as simple as a child. If it had all gone to ruin it would be Jonathan’s mother’s fault for putting all her faith in her eldest son to the detriment of the others. Some said, secretly, that Ruth was getting what she deserved, for she had worshipped Jonathan and turned a blind eye to all his womanizing. To think all this trouble could’ve been averted if they’d just let Jonathan wed you!” I knew Jonathan wouldn’t have married me, but Sophia didn’t know this. As far as she knew, he’d run off with me, leaving the impression that he’d been madly in love with me.

“But God provides for his flock, doesn’t he, even those as undeserving as Ruth St. Andrew and the pitiless magpies of this town,” Sophia said with some spite, lifting her skirts as she stepped primly over a fallen log. “For Benjamin managed to come along a bit, enough to work with the logging foreman, and with time earned the respect of most of the town for being an honest man and not nearly as manipulative as the rest of his family.” It was plain by her tone that she included Jonathan among the manipulative ones.

“Do you remember Evangeline? The wife you wronged?” Sophia asked, again delighted for being able to taunt me. “Poor thing—as though anyone needed further proof of the misfortune of being Jonathan’s bride! What a miserable time she had of it when Jonathan abandoned her. She lived in a state of perpetual shame. She left the St. Andrew house and moved in with her parents to raise her daughter, much to Ruth’s chagrin. She wanted that babe under her roof, she did. Benjamin made a campaign of wooing her, and at length she consented to wed him—perhaps the wisest decision she ever made. Though she waited until Ruth passed to give Benjamin her answer, for who would be eager to live under the same roof as that old witch again? But it seems your shameful deed brought about one blessing. You can thank the Lord for that kindness.”

I devoured Sophia’s news. Over the years, I’d speculated many times about what had happened after Jonathan and I left town. It wasn’t surprising to hear that I’d been vilified, but I was saddened to learn that my family had suffered unjustly for what I’d done. It reminded me how judgmental the people of my town could be, these descendants of Puritans, hardened all the more by privation. How stifling it had been, growing up in their midst.

“So, my family was ruined?” I asked, my voice faltering.

This time, she looked over her shoulder at me, and there was a vulpine smile on her lips. “Ruined, as they deserved, for raising the likes of you. But you shall see for yourself.”

After a few turns through the dark woods, we came to a cabin sitting in a clearing. I recognized the house at once as the one I had grown up in, though the land around it was not the same, and the whole vision had the distorted feeling one gets in a dream. Sophia opened the door and went inside with quiet authority, and so I followed her. The first thing I noticed was that the house had gone to ruin since my last visit. The logs in the walls had shrunk, loosening the wadding that plugged the joints and cracks, and let the wind and cold seep through. The rooms were austere, thinned of furniture. The overall impression was of a life suffered, made pinched and meager. I thought at first that the cabin was empty, but then I noticed one of my sisters crouched by a crude wooden chest. It took a minute to tell that it was Fiona, as she appeared much older than the last time I’d seen her. She continued to pack items into the chest, humming softly as she worked.

“She’s leaving,” I said aloud as I watched her.

Sophia nodded, shifting the baby in her arms. “Yes, she’s going to Fort Kent to be married.”

“For a bride, she doesn’t look happy.”

A vexed look crossed Sophia’s face, but rather than reprimand me, she said, “She’ll be joining your other sister.”

“Glynnis? She lives in Fort Kent?”

“She married a farmer out that way a year ago, and she’s arranged for Fiona to wed a widowed neighbor.”

“And where’s my mother? Is she living with Glynnis?” I asked, but I knew the answer even before the words were out of my mouth. My nose stung as I fought back tears that I didn’t think would still come after all these years.

“No, Lanore. Your mother is gone. She passed last winter from pleurisy.” Sophia said this flatly, taking no pleasure in delivering the bad news to me. Of course, intellectually I knew my mother had been dead and gone a long time, but standing there in the house I grew up in, where I’d always seen my mother at the hearth or bustling about, Sophia’s news hit like a blow to my chest.

I shook my head, trying to shake off the sadness, and turned my attention back to my sister. “Poor Fiona, marrying a stranger.”

Sophia’s face twisted again with displeasure. “We all marry strangers, Lanore. Even if it is someone you know, he won’t be the same person once you are wed. Besides, none of us married for love. Everyone you knew married out of duty and in order to survive: your parents, your neighbors . . . even Jonathan. Love does not equal happiness,” she said sharply.

She was right, of course, yet I couldn’t help muttering, “And still, love is the greatest happiness I have known.”

Sophia was surely about to say something cutting in response to my last remark when the door swung back and my brother, Nevin, stepped in. By now, I knew to expect he would look older, but I wasn’t prepared for this drastic change. He was grizzled and hunched and seemed to have aged twice as fast as Fiona, his appearance ravaged by his work outdoors, regardless of the weather, looking after the cattle. His face was heavily lined and his cheeks pitted as though he’d suffered a recent bout of smallpox. He stomped his feet to knock the mud off his shoes and hung his hat on a peg, but kept his coat on.

“Are you ready to go?” he asked Fiona.

“Almost, but I need to pack a few more things. I’m afraid we’ll be leaving so late that you’ll need to spend the night with Glynnis and John . . .”

Nevin had begun shaking his head before she’d finished speaking. “No, you know I can’t do that. Who would take care of the animals? I cannot leave the farm untended overnight. I must get back this evening.”

“Nevin, I hope you’ll end this stubbornness and take on a field hand. You can’t do this on your own. You’ll need someone to help you.”

She had the tone of someone who already knew their words would fall on deaf ears, however. Nevin shook his head vehemently as he stared at the tips of his shoes. “We’ve been over this already, Fin”—his nickname for her—“I’ve no reason to take on a boy. It’ll only be another mouth to feed. The farm is small enough that I can manage by myself.”

“That’s not true and you know it,” she protested but softly. “What if you get sick?”

“I won’t get sick.”

“Everyone gets sick. Or lonely.”

“I won’t be lonely, either.”

Nevin was like a drowning man flailing too fiercely to be saved, Fiona forced to row away in a lifeboat, abandoning him to save herself. No one else in the family would blame her, but that would be little solace when things went to ruin later. “I’ll be fine,” Nevin said gruffly.

“Will you be able to return for the wedding?” Fiona asked, lowering the chest’s lid.

“You know I can’t. I have the animals to see to. You don’t need me, anyway. You’ll have Glynnis to attend to you.”

Fiona said nothing, for it wasn’t worth arguing with him anymore.

“They’ll not see each other again,” Sophia leaned and whispered to me as though we were watching actors in a play. Still, she spoke with the confidence of a prophet.

“Why—does something happen to Nevin? To either of them?” I asked, anxious. “What happened to my family? I’ve always wanted to know . . .”

She let her hollow gaze settle on the floor and not on me, mercifully, and dandled the baby high and close to her chest. “Nevin will live for another ten years. He does not take on any help for the farm and ends up dying alone one winter, his lungs filled with fluid, too weak to build a fire for himself.”

I bit my lip and felt a flash of bitter pain. Stubborn Nevin.

“Your sister Fiona will die in childbirth with her first child,” she said, nodding at my sister on the floor in front of us. “As for Glynnis—”

“Tell me at least one of them finds happiness,” I burst out.

“She is happy enough. Her husband is a good man and they have four children together, three boys and a girl.”

“Thank God,” I said, and meant it. My eyes filled with tears as I watched Fiona finish her packing. Time had worn away a little of my sister’s prettiness; she and Glynnis had been far prettier than I when we were girls. They had been the bright and winsome ones, quiet daughters who—unlike me—didn’t break their parents’ hearts and ruin their lives. It seemed cruel of fate to keep Fiona shackled to our family for so long (she was probably in her mid-twenties as she stood before me) only to have her die before she could have a family of her own. I hoped that this farmer she was to wed was a good man who appreciated her, and that he thought fondly of her for as long as he lived.

Even Nevin’s future seemed especially cruel. That he would live his entire life alone wasn’t so unexpected given his prickly nature, but in ten years he would only be in his forties. If we had lived farther south where the winters were not so long and brutal and life was not as demanding, he might’ve survived longer even though he lived on his own. There was good reason why the Puritan edict against solitary living was usually enforced in St. Andrew, for this practical consideration as well as the religious (which was so no soul would fall into ungodly behavior as there would always be a witness to steer him back on the path of goodness or turn him in, as the case may be).

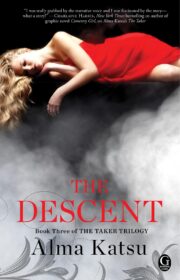

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.