He pressed a hand to the cover, quite filthy by now, with centuries of grime effacing the blue linen, and he could practically feel magic emanate from it like a pulse. Cosimo’s magic; he’d felt the same jangly vibrations in Cosimo’s presence, just as he assumed others felt something similar when they were near him. Once a person made contact with the other world, it left its mark on him. It had made Adair into something like a portal, with the hidden, magical world a heartbeat away.

ELEVEN

Once I stepped through the door of the Moroccan hotel, I was back in the fortress, presumably in the hall on the second story. The dusty smell of the hotel in Fez lingered, however, clinging to my sweaty skin and damp cotton dress, proof that it hadn’t been completely fabricated in my mind—unless the subtle mix of ginger, mint, sandalwood, and jasmine were also figments of my imagination.

The hall was still a dim and empty expanse of red carpet and dark wooden doors. No sound echoed down the long corridor, the house as quiet as a mausoleum. In the unbroken stillness, I suddenly noticed that the flames standing atop the candles in the iron wall scones had begun to quiver, tickled by a draft coming from an unknown direction. Someone had opened a door.

I strained so hard listening for a sound that my ears started to ache. Then I heard what I’d been waiting for: a muffled thump, like a ball being dropped onto a carpet. And a second thump. Whatever it was, it sounded very solid, ominously so. The cloven hoof of a demon? I wasn’t going to stay and find out. My hand closed around the nearest brass doorknob. I gave it a turn, held my breath, and slipped inside another room.

I stepped into a forest, just on the other side of the door. The forest was vast—I could tell by the vacuous silence—and a light snow was falling; only a few flakes made it through the canopy of bare branches to the ground. A fuller stand of trees stood ahead of me, mostly pine and all frosted with new snow, and behind it another stand and another. My breath misted on the cold air and my skin tingled—not from the cold but because I was home.

I knew without needing to be told that I was in St. Andrew. How did I know this? After all, I could be in a forest anywhere, but I knew. The land was as well known to me as a painting I’d looked at a thousand times. The air tasted familiar; it even felt familiar against my skin, though of course all of this could have been a trick of the mind. Still . . . the birdsong, the slant of light. Everything told me I was in St. Andrew.

Again, it made no sense that I should be here. Perhaps it had to do with the way the afterlife was configured, hardwired to the time we spent on earth. The dour, judgmental Puritan in me would like to believe that it was designed to throw me back to the place or events that were most important to me, to revisit the lesson I missed in life. That is, if there was an order to things at all, which the realist in me doubted.

I walked toward the trees, wondering where I was in the Great North Woods, a forest famous for swallowing up people and not letting them go. The great woods went on for miles in sameness, and it was easy for even experienced wilderness guides or, in my day, axmen and surveyors on horseback, to lose their way. As I came to a thinning of trees, I heard the faint sound of running water and followed the noise until I came to the river.

Within minutes the Allagash unfurled before me. There was no mistaking it, broad and flat and calm. It might’ve been snowing, but it was not cold enough to cause the river to freeze over. The only strange thing I noticed about the river this day was that it was unusually dark. Black, as though a river of ink rushed over the rock bed. It must be a trick of the light, I told myself, a reflection of the overcast sky and not an ominous sign portending ill fortune.

My sense was that the village lay on the other side of the rolling water. I wondered if the river was shallow enough at that point to walk across. It looked to be, though the water was sure to be painfully cold. However, when I scanned the river’s edge for its narrowest point, I suddenly saw an empty rowboat nestled in a tangle of dead vines. The boat was weathered to a silvery gray, an old and forgotten thing, crudely made. A paddle lay across the plank seat.

I climbed in, pointed its nose toward the opposite shore, and began paddling. There were stretches of the Allagash that were very gentle, and I assumed from the current that this was one of them, but was surprised nonetheless by the ease with which I reached the other side, not quite as though the boat knew what was expected of it but nearly so. It nosed onto a sloping part of the riverbank as neatly as though strong hands had pulled it ashore for me, so it was nothing to step out and onto dry land.

A path showed itself through the trees and I followed, having no better idea of which way to go, and I didn’t have to walk very far before I saw someone in the distance. As I got closer, I saw that it was a woman in a long, dark coat sitting on a tree stump with what appeared to be a baby in her arms. Her straight dark hair had fallen across her face like a curtain, obscuring my view of her. I knew without question that she was waiting for me.

Despite the crunch of my shoes in the snow, she did not look up until I was practically standing next to her, confirming it was who I’d begun to suspect: Sophia Jacobs, the woman who had once been Jonathan’s lover but had taken her own life—and that of her unborn baby.

I was startled—almost frightened—to see her again. When we were young women together in St. Andrew we hadn’t been friends and she even had reason to hate me. I had tried to make her give up Jonathan, to hide the paternity of the baby he’d put inside her, but instead, she drowned herself in the Allagash, near this very spot. I’d thought little of her since Jonathan had absolved me of any guilt in her suicide, taking the blame on himself. And though I’d dreamed of her many years ago, when my trespass against her was still fresh, in none of those dreams had she ever been this vivid. She looked exactly as I’d last seen her in life, but seeing her this closely revealed a hundred tiny details I’d perhaps forgotten with time. Had she always been so worried and nervous? Were her eyes always this sunken, her skin ashy, her mouth hard set in a half frown? And in her arms was a bundle of swaddling that she held like a baby.

“Sophia,” I said by way of greeting, puzzled as to why I’d been brought to her.

She shifted the bundle in her arms, regarding me coolly. “Well, you took long enough getting here. Come along now, you’ve much to see.”

“What do you mean? I don’t understand—why’d you bring me here?”

She was rising to her feet but froze at my words. “Bring you here? No, it’s the other way around. I’m here because of you. Don’t dawdle now. We’ve got to be going.” She didn’t wait for my reply but set off at a strong pace through the snow, the baby held tight to her chest.

Within minutes we were at the edge of town. St. Andrew looked the same as it did in my childhood memories: the long clapboards of the congregation hall; the common green in front, now covered with snow, where we spent many an afternoon in the company of our neighbors after services; the fieldstone fence that surrounded the cemetery; Parson Gilbert’s house; Tinky Talbot’s smith shop; the path next to the blacksmith’s leading to Magda’s one-room whorehouse; and farther down the muddy, choppy road, Daughtery’s poor man’s public house, shuttered up against the snowfall.

Faces of the people I’d known when I’d lived here as a child—my family, friends, the townspeople who ran the businesses and occupied the farms that had flanked ours—spun past my eyes, people I’d missed more dearly than I would’ve thought possible. “Wait, Sophia,” I called to the thin figure bustling ahead of me. The top of her head and her sloping shoulders were white, as though she’d been dusted with sugar, and the hem of her long coat swept a wide path behind her. “Can you tell me what happened to everyone? You don’t know how often I’ve wondered . . .”

She walked on purposefully, keeping her gaze trained on the ground before her. “If you really wish to know about St. Andrew, the horrors that befell us, I’ll tell you.” Her tone was grimly smug, thick with schadenfreude. “The entire town was torn apart when you and Jonathan ran away.” It was then I realized that for all her ghostly qualities, Sophia was not omnipotent and was unaware of the circumstances of my abrupt departure. It may have looked to outsiders that I’d returned to the village intent on stealing Jonathan’s heart, but I’d come armed with Adair’s elixir of life, under orders to bring Jonathan back to Boston with me. But when I returned to St. Andrew, I found the town dependent on Jonathan: he ran the logging operation, the most profitable business in town by far, and held the mortgage to nearly every farm. I had no heart to take him away from a town that needed him. Fate interceded, however, and when Jonathan was shot by a cuckolded husband, I was left with no choice but to give him the elixir and whisk him out of town to keep our secret from being discovered.

“There was a terrible row when it was discovered that you’d gone,” Sophia continued with relish. “Jonathan’s family was exceedingly angry with yours, taking your mother to task for raising such a wicked girl. The town divided on the matter, for and against, and you’ll not be surprised to learn that very few stood with your family. You were called all sorts of vile names—whore, harlot, Jezebel”—she seemed particularly delighted to recall this bit of history for me—“and there was some talk of forcing your family to compensate the St. Andrews for their loss.”

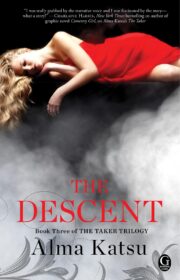

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.