His request had the desired effect on Rossi: flattered, the bishop preened like a swan. “Oh, my boy, I would be only too happy to be your adviser. Your spiritual guide, as well as your friend.” The bishop clasped one of Adair’s hands in both of his and gave it an affectionate shake before the two men continued in their work.

Once the mercury reduction was under way in earnest, conversation petered out. As Adair sat with the older man in the dungeon room, breathing in the noxious air and sweating like the devil from the heat, he considered his position once again. Salvaging his relationship with Rossi had been an astute move: the bishop would’ve said something to the doge, undoubtedly, and Adair thought of his father and how mad he would be if his son were arrested for the very thing they’d tried to avoid by sending him to Venice.

He left the bishop’s palazzo in the hour before dawn, his host fallen asleep in a chair by the sweltering fireplace. With Adair’s attention elsewhere, the reduction was ruined, seized up solid into a tiny rock smaller than a baby’s fist. Good for nothing now. Adair left it on the worktable and slipped out of the sleeping household to make his way back to the doge’s palazzo.

In the weeks that followed, Adair noticed that whenever he went to see the bishop, usually late in the evening after one of Professore Scolari’s lectures, Elena would be waiting for him, laced into one of her beautiful silk gowns, her hair pinned and her skin bathed in lavender-scented oils. Adair noticed that the bishop always managed to be detained each time he arrived, and wondered if his delay wasn’t intentional in order to give his ward a few minutes alone with the Hungarian nobleman. Adair couldn’t help but wonder why the bishop would encourage these unchaperoned exchanges with his goddaughter. After all, he was a foreigner; surely Elena’s family would prefer to see her wed to an Italian lord and not whisked off to a kingdom far away, where it was possible they’d never hear from her again.

In any case, Adair had no intention of returning to Magyar territory if he could help it, and without property of his own, he certainly could not take a wife. Besides, he was tiring of Rossi’s company—the bishop warming to his new role as Adair’s spiritual adviser and taken to repeating his favorite sermons during their sessions in the laboratory—and didn’t want to complicate matters with Elena when her godfather clearly had ulterior motives in having them spend time getting to know each other.

That evening, as he traveled through cobbled alleys in the dark, he realized he must make this plain to Elena, if not Rossi. He practiced what he would say to her: Do not set your sights on me, because I have no interest in acquiring a wife, not now, not ever. Huddled inside his great cloak, with his face hidden under the brim of his hat, he marched briskly through the square to the bishop’s handsome palazzo, summoning the courage to set Elena straight.

Telling her to her face would be another matter, however.

He had no sooner surrendered his cloak and hat to a servant than Elena hustled down the staircase, her timing so perfect it was as though someone had rung a bell to let her know he was there. She was more radiant than usual tonight, in a pale yellow gown that set off her dark hair, and his throat caught at the sight of her. He bowed low to her, heat rising to his cheeks. As always her beauty brought out something awkward in him, made him clumsy and thick-tongued. His mother had always kept her sons from spending time with the ladies at court, and frowned on too much familiarity with serving girls as well. As a result, even though Adair and Elena were close in age, he felt that she had an advantage over him when it came to dealing with the opposite gender.

“Good evening, Elena,” he said cautiously. “How have you been since we last saw each other?”

Her dark eyes latched onto his as she described how she’d passed the time: going to mass in the morning, afternoons spent working on an embroidery project with the old nurse for company, dinners at the bishop’s table hearing about his day. Her days never changed. How boring it must be for her, he thought, shut up in her godfather’s bachelor household with no girls her own age with whom to gossip and play. Did Rossi let her go to balls or dances? What had she done to cause her family to send her away to Venice, he wondered? There was something about the girl’s and the bishop’s behavior that made him think there was more to the story. Or perhaps they’d sent her in the hope that she’d make a better match under the bishop’s guidance?

She placed a hand on his forearm to get his attention, and Adair imagined he felt the heat of her tiny hand through the layers of his clothing. “Tell me . . . don’t you wish to visit with me one evening, instead of my godfather? I think I would be much better company. You might read to me from your favorite poems. I would like that very much,” she said.

“Why certainly, Elena, if your godfather would permit it,” Adair replied. Though he knew he shouldn’t encourage her, he felt pity for the girl. At his positive response, her pretty face lit up and she dropped her gloveless hand on his, so their skin touched for the first time. She might as well have set his hand on fire. After a momentary dizziness, he recalled his earlier decision—to never take a wife and be married instead to science—and opened his mouth to speak. It would be caddish to mislead her.

“Elena, there is something I must tell you, however—”

Her dark eyes widened at his words. “Oh no. You are already betrothed! Is that what you were going to say?” She clutched his arm, this time digging her fingers into his sleeve.

“No, Elena. It’s not that, not at all.” The emotion in her voice caught him off guard. With Elena, his head clouded. She was a thing of both extraordinary liveliness and tempting softness, from the glossy dark curls on her head to the organdy tucked along the neckline of her gown. The scent of warm lavender oil rose from her bare throat. She was a beautiful little present, wrapped in silk and lace.

“Then there is no problem if you were to kiss me.” She smiled at her own daring. She lifted her chin and closed her eyes, clearly expecting him to take up her offer. He tingled with fear and desire. He had little experience kissing in passion aside from a few experiments with his cousins back in Hungary. The few whores he had known did not expect, or even particularly want, to be kissed. He tried to put these thoughts out of his mind as he looked at Elena. Why not kiss the girl? They were alone, no chaperones hovering at their side. The bishop’s footsteps echoed down the hall, but he was still a distance away.

The seconds ticking by, Adair closed his eyes and kissed her. Her softness yielded to him. He felt as though Elena wanted him—perhaps even more than he wanted her—and the idea of being desired stirred him. He leaned into her, pulling her tighter, and she responded, her mouth opening for him. And just as he felt he could pour himself into her until they became one, a hand fell on his shoulder. It was the bishop.

Adair sprang back, his heart leaping, but there was no enraged outcry from his host, no shove propelling him away from the young woman. Adair expected Rossi to lose his temper and accuse Adair of taking advantage of his hospitality, but no—Bishop Rossi was smiling. He clapped Adair on the back. “My boy, don’t be embarrassed on my account. It is only natural to have such feelings for a young lady as beautiful as my goddaughter.” Why, he practically beamed with happiness, and Elena, for her part, stood behind her godfather, blushing so furiously that her cheeks were like two perfect red apples.

In the laboratory that evening, the bishop’s mind seemed to wander, and so Adair took command of the experiment, measuring ingredients onto tiny silver salvers and tending the furnace while the bishop continued to wax eloquently about his ward. “Have I told you about her family, back in Florence? It’s very old, a fine family. It goes all the way back to the duchy’s beginnings. Her family has had their estate in the valley for as long as anyone can remember.” Adair listened but didn’t respond; the girl’s pedigree meant nothing to him since he had no intention of lengthening her family tree.

“And Elena is such a clever girl. She knows a little French, and Latin, of course, for mass. But she has other talents, too. . . . She dances like an angel, and sings beautifully. I always have her sing at my dinner parties for my guests and—why, we must have you over for one soon. We shall make you the guest of honor. Would you like that?” the bishop asked excitedly, as though the thought—after weeks of Adair’s company—had only just occurred to him.

“Certainly,” Adair replied, but only to end Rossi’s chattering. Even Elena’s kiss and snowy-white décolleté were fading from memory, unable to compete with the allure of the laboratory.

“Excellent! I will speak to my housekeeper to make the arrangements,” the bishop said, and beamed. Rossi clearly had no interest in their experiment that night; he was on a mission of a different kind. The old cleric studied Adair with an appraising eye. “She is a very lovely girl, wouldn’t you say? She’s considered one of the most beautiful girls in Florence, you know.”

She certainly spent enough of her father’s money on gowns and jewels, Adair thought. He put down the tiny pair of pincers he was using to count out crystals of salts of alum. “If that’s the case, why has she been sent here to live with you? If she is one of the most eligible girls in Florence, shouldn’t she be betrothed already?”

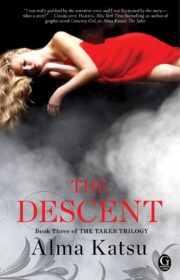

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.