Savva became quite animated at this point, caught up in his tale, and he sped up his gait, hurrying me along even faster down the street. “One of my friends grabbed my hand and said we’ve got to go, that the queen was coming. And he pulled me toward the exit at the back of the room, only everyone was headed in the same direction, and before we could get to the doors we heard someone call out, ‘Make way! Make way for your queen!’

“And then the crowd parted and I saw them step onto the dance floor, the demons.” Savva tried to suppress a shudder. “That was the first time I saw them, but it wouldn’t be the last. Hideous things, they are, half-man, half-beast. They were the embodiment of evil. There were two of them, snorting like horses and scanning the crowds as though they were looking for someone. Then this woman stepped on the dance floor between them.

“I could tell she wasn’t human right from the start; she was so tall and thin and spectral. She was wrapped in a black cloak that covered her from her throat to her shoes, and in the darkness it just looked like her head was floating through space. She had flaming red hair that danced about her head as though it were alive, like Medusa’s snakes. The queen has the face of a predator, high cheekbones and hungry eyes. Sharp, cunning. She, too, was looking over the crowd. You could tell by the delighted expression on her face that she was on the hunt, looking for prey.

“She finally found what she wanted, a handsome boy with blond curls and blue eyes—a boy who didn’t look all that different from me, really. I sometimes wondered if she hadn’t been looking for me that night, though I can’t imagine why she would. She snapped her fingers at her demon guards and they took hold of the boy, each hooking one of his arms in theirs, and dragged him away.”

“What did she do to him?” I asked, aghast.

“I don’t know. Nobody knows what she does with the unfortunates, though it’s rumored that she makes them disappear. My friend told me that whomever she chooses is never seen again.”

The queen’s inclination for pretty men could explain why she was holding Jonathan. “What about the demons? Do they roam around freely?” I asked.

“No. You never see them except in her company. I assumed they were her bodyguards or something like that. Her royal guard. She is the queen, after all.” He tilted his head thoughtfully and laid a hand on my arm. “Are you sure you want to do this? Go up against the queen and her demon guards? Oh, but what am I saying. It’s Jonathan we’re talking about. Wild horses wouldn’t stop you.”

We were back at the entrance to the hotel, the sun starting to slant sideways, the day half-gone (or pretending as much). I squeezed both of Savva’s hands in mine. They were fine-boned and silky, and I noticed he had on his old rings, a gold signet and a large, square-cut emerald, ones he’d sell to secure our freedom from an Algerian pirate, later in our personal timeline. “It was good to see you, Savva. And thank you for the information. But I’d better be going. . . .”

He held me fast. “Don’t go yet, Lanny. Who knows when we might see each other again, if ever?” His eyes got a little damp. “You can give me an hour more, surely you can. Let’s order tea. They do a fabulous high tea here, you really must indulge me,” he said, ignoring my weak protests and raising a hand to flag down one of the hotel staff.

Plates of butter cookies layered with raspberry jam and lemon curd and dusted with sugar. Scones and clotted cream. Crustless watercress-and-cucumber sandwiches cut into tiny batons. A pot of luxuriant Ceylon tea for me, better than any I could recall ever having in real life, and for Savva, a tall sparkling gin and tonic (for “tea” would never mean tea for Savva). This banquet was brought to us on a large brass tray made into a table with the addition of a little wooden tripod, and was placed between our two chairs. The fact that the hotel did not serve anything like this proper English tea in 1830 was not lost on me, but I took a page from Savva’s book and decided to suspend disbelief and go with the flow while I was here in the underworld.

Amid the lush spread, I asked Savva how he’d met his end, curious to know how Adair had handled his release, whether he’d treated Savva kindly. By then, Savva had been in worse shape than the last time I’d seen him, and had moved from his apartment in the medina to a tenement building in a rough neighborhood outside of Casablanca. It was the very last thing he could afford, Savva admitted, the next step being squatting with other junkies in an abandoned, condemned building. Adair must’ve been shocked to see what had become of the charming boy he’d once known, the bon vivant who had grown up on the fringes of aristocracy in the beautiful city of St. Petersburg.

According to Savva, Adair had turned up out of the blue at the apartment one evening. He didn’t have to break in, as the door had been open; more often than not, in a drugged stupor Savva failed to remember to latch the door. Adair found him asleep on a bed in the filthy, disheveled apartment, fully dressed except for shoes and socks, his face blank and dreamless. A few objects had stood on the nightstand: a candle stub, still burning, and his rig—a syringe, a spoon, and a shoelace, much used and fraying.

“Is it you, Adair, really you, come to see me after all these years?” Savva had muttered to his visitor, eyes rolling under half lids. He’d thought he imagined Adair at his bedside, the man who had lost interest in him long ago.

But Adair had kept staring at him, horrified and speechless. “It was so obvious that he was pitying me. It was unsettling,” Savva confessed. “I never would’ve thought it possible, you know. To him, pity was a useless emotion. I must’ve been nearly unrecognizable to Adair, jaundiced and drawn by long weeks—months!—without so much as a bite to eat.” I pictured his blue eyes gone dull, his skin as lifeless as a dried corn husk, his hair thin. “Adair couldn’t believe I’d gotten that bad. He thought we would never change, no matter what we did. I think he was shaken that I had managed to spoil his handiwork.”

Adair had explained how he’d come at my request, Savva told me. “It’s not as though I wanted you dead,” I protested, coloring at having been found out, but he waved my concern aside. “I understand why you did it, Lanny, and I’m grateful. I didn’t want to live forever. We’re not meant to, we’re not built for it, some of us less so than others. I’m a weak vessel; I accept that. Life had become unbearable for me and you knew it. I was glad that Adair had come. Strangely, though, he didn’t want to end my life, even after seeing what had become of me. He talked of helping me, rehabilitating me—Adair, can you believe it? He even told me that he was sorry for having caused me to suffer, which made me laugh out loud. I couldn’t believe my ears. Adair, apologizing. Can you imagine it?”

Savva’s words comforted me. I was glad for proof that Adair had changed beyond what I’d seen for myself on the island. The fact that he could have compassion for someone besides me proved that he didn’t act only in his own self-interest. He was willing to change in order to make me happy. The reserve I held in place, to keep from completely falling in love with Adair, melted a tiny bit.

“I finally did it, you know,” Savva continued in a serious tone, snapping me out of my reverie. “I confronted him. ‘I never understood why you chose me,’ I told him, ‘or why you let me live when you so obviously stopped having any need of me. I shouldn’t have been a coward, that day I left your household. I should’ve asked you to kill me instead of letting me go. I’ve been trying to kill myself, anyway, ever since. So, yes, I want you to do as Lanny asked,’ I told him. ‘I want you to kill me.’ And he did.” Savva took a long drink from his gin and tonic, happy in a childish, spiteful way.

“How—how did he do it?” I asked, barely able to ask and yet possessed by morbid curiosity. Would there be some kind of ceremony to it? It couldn’t be as straightforward as ending a mortal life, could it?

Savva became still. “He made me close my eyes. Then he put his hands around my throat—those strong hands, so deft—and broke my neck. It was over in a second.” He snapped his fingers and I jumped at the sound. “Adair was gentle as a lamb about it, so concerned that he might cause me a second of pain. He was almost the way he’d been at the beginning when he first saved me and made me immortal—courtly, you know? When he loved me. Funny—Adair was always a bit like a father to me. I suppose that sounds horribly twisted, but there you have it. To me, he was the capable older man who was going to take care of me. I think he saw himself that way, too, and that’s why it bothered him that I’d been stumbling around, lost, feeling unwanted. It was like he just realized that he’d failed me.”

“Is that what this has all been about?” I asked softly. Savva’s self-destructiveness and unhappiness: Had it all been because Adair had ceased to want him? Had he been wandering the world unhappily because he had been cast out of Adair’s life and forced to go on without him?

Savva laughed archly as he tossed his napkin to the table. “Oh, my dear, you needn’t be so melodramatic. It isn’t entirely Adair’s fault, as much as we like to blame him for all our troubles. I brought baggage of my own: I was looking for a big, strong man to make me feel safe and secure.” His words resonated with me more than I wanted to admit.

We spent the next half hour nibbling on tea cookies and analyzing the man who fascinated us both. “It is always a case of mutual attraction,” Savva said with conviction; it was obviously a matter to which he’d given considerable thought. “Attraction is a very curious thing, you know. We’re rarely attracted for the reasons we think; it’s the subconscious at work. In all our cases, we were drawn to Adair, and he to us. There was something in him that we were looking for, each of us in our way. I wanted a father—I admit it—and he, perhaps, wanted someone who would adore him like a son. Tilde admired his power because it was what she wanted for herself.” I hoped he’d stop short of psychoanalyzing me. I didn’t want him to peer into my heart and pluck out the weaknesses that had drawn me to Adair. I’d rather not think that I was drawn to Adair out of weakness. I wanted to believe that I knew Adair now, and was falling in love with him with eyes wide open—nor did I want to admit to Savva that I’d fallen in love with the man I’d once feared and loathed.

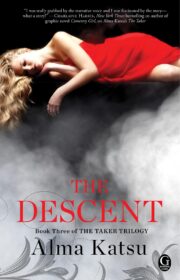

"The Descent" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Descent". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Descent" друзьям в соцсетях.