“Don’t tell me you knew him!” exclaimed Cedric.

“Not very well. We happened to meet him here.”

“I’ll tell you what, my lad: he was no fit company for a suckling like you,” said Cedric severely. He frowned upon her again, but apparently abandoned the effort to recall the errant memory, and turned back to Sir Richard. “But your cousin don’t explain your being here, Ricky. Damme, what did bring you to this place?”

“Chance,” replied Sir Richard. “I was—er—constrained to escort my cousin to this neighbourhood, upon urgent family affairs. Upon the way, we encountered an individual who was being pursued by a Bow Street Runner—your Runner, Ceddie—and who slipped a certain necklace into my cousin’s pocket.”

“You don’t mean it! But did you know Bev was here?”

“By no means. That fact was only revealed to me when I overheard him exchanging somewhat unguarded recriminations with the man whom I suppose to have murdered him. To be brief with you, there were three of them mixed up in this lamentable affair, and one of the three had bubbled the other two. I restored the necklace to Beverley, on the understanding that it should go back to Saar.”

Cedric cocked an eyebrow. “Steady now, Ricky, steady! I’m not cork-brained, dear old boy! Bev never consented to give the diamonds back—unless he was afraid you were going to mill his canister. Devilish lily-livered, Bev! Was that the way of it?”

“No,” said Sir Richard. “That was not the way of it.”

“Ricky, you fool, don’t tell me you bought him off!”

“I didn’t.”

“Promised to, eh? I warned you! I warned you to have nothing to do with Bev! However, if he’s dead there’s no harm done! Go on!”

“There is really very little more to tell you. Beverley was found—by me—dead, in a spinney not far from here, last night. The necklace had vanished.”

“The devil it had! Y’know, Ricky, this is a damned ugly business! And, the more I think of it the less I understand why you left town in such a hurry, and without a word to anyone. Now, don’t tell me you came on urgent family affairs, dear boy! You were disguised that night! Never seen you so foxed in my life! You said you were going to walk home, and by what the porter told George you had it fixed in your head your house was somewhere in the direction of Brook Street. Well, I’ll lay anyone what odds they like you did not go to serenade Melissa! Damme, what did happen to you?”

“Oh, I went home!” said Sir Richard placidly.

“Yes, but where did this young sprig come into it?” demanded Cedric, casting a puzzled glance at Pen.

“On my doorstep. He had come to find me, you see.”

“No, damn it, Ricky, that won’t do!” protested Cedric. “Not at three in the morning, dear boy!”

“Of course not!” interposed Pen. “I had been awaiting him—oh, for hours!”

“On the doorstep?” said Cedric incredulously.

“There were reasons why I did not wish the servants to know that I was in town,” explained Pen, with a false air of candour.

“Well, I never heard such a tale in my life!” said Cedric. “It ain’t like you, Ricky, it ain’t like you! I called to see you myself next morning, and I found Louisa and George there, and the whole house in a pucker, with not a man-jack knowing where the devil you’d got to. Oh, by Jupiter, and George would have it you had drowned yourself!”

“Drowned myself! Good God, why?”

“Melissa, dear boy, Melissa!” chuckled Cedric. “Bed not slept in—crumpled cravat in the grate—lock of—” He broke off, and jerked his head round to stare at Pen. “By God, I have it! Now I know what was puzzling me! That hair! It was yours!”

“Oh, the devil!” said Sir Richard. “So that was found, was it?”

“One golden curl under a shawl. George would have it it was a relic of your past. But hell and the devil confound it, it don’t make sense! You never went to call on Ricky in the small hours to get your hair cut, boy!”

“No, but he said I wore my hair too long, and that he would not go about with me looking so,” said Pen desperately. “And he didn’t like my cravat either. He was drunk, you know.”

“He wasn’t as drunk as that,” said Cedric. “I don’t know who you are, but you ain’t Ricky’s cousin. In fact, it’s my belief you ain’t even a boy! Damme, you’re Ricky’s past, that’s what you are!”

“I am not!” said Pen indignantly. “It is quite true that I’m not a boy, but I never saw Richard in my life until that night!”

“Never saw him until that night?” repeated Cedric, dazed.

“No! It was all chance, wasn’t it, Richard?”

“It was,” agreed Sir Richard, who seemed to be amused. “She dropped out of a window into my arms, Ceddie.”

“She dropped out of—give me some more burgundy!” said Cedric.

Chapter 13

Having fortified himself from the decanter, Cedric sighed, and shook his head. “No use, it still seems devilish odd to me. Females don’t drop out of windows.”

“Well, I didn’t drop out precisely. I climbed out, because I was escaping from my relations.”

“I’ve often wanted to escape from mine, but I never thought of climbing out of a window.”

“Of course not!” said Pen scornfully. “You are a man!”

Cedric seemed dissatisfied. “Only females escape out of windows? Something wrong there.”

“I think you are excessively stupid. I escaped out of the window because it was dangerous to go by the door. And Richard happened to be passing at the time, which was a very fortunate circumstance because the sheets were not long enough, and I had to jump.”

“Do you mean to tell me you climbed down the sheets?” demanded Cedric.

“Yes, of course. How else could I have got out, pray?”

“Well, if that don’t beat all!” he exclaimed admiringly.

“Oh, that was nothing! Only when Sir Richard guessed that I was not a boy he thought it would not be proper for me to journey to this place alone, so he took me to his house, and cut my hair more neatly at the back, and tied my cravat for me, and—and that is why you found those things in his library!”

Cedric cocked an eye at Sir Richard. “Damme, I knew you’d shot the cat, Ricky, but I never guessed you were as bosky as that!”

“Yes,” said Sir Richard reflectively, “I fancy I must have been rather more up in the world than I suspected.”

“Up in the world! Dear old boy, you must have been clean raddled! And how the deuce did you get here? For I remember now that George said your horses were all in the stables. You never travelled in a hired chaise, Ricky!”

“Certainly not,” said Sir Richard. “We travelled on the stage.”

“On the—on the—” Words failed Cedric.

“That was Pen’s notion,” Sir Richard explained kindly. “I must confess I was not much in favour of it, and I still consider the stage an abominable vehicle, but there is no denying we had a very adventurous journey. Really, to have gone post would have been sadly flat. We were over-turned in a ditch; we became—er—intimately acquainted with a thief; we found ourselves in possession of stolen goods; assisted in an elopement; and discovered a murder. I had not dreamt life could hold so much excitement.”

Cedric, who had been gazing at him open-mouthed, began to laugh. “Lord, I shall never get over this! You, Ricky! Oh Lord, and there was Louisa ready to swear you would never do anything unbefitting a man of fashion, and George thinking you at the bottom of the river, and Melissa standing to it that you had gone off to watch a mill! Gad, she’ll be as mad as fire! Out-jockeyed, by Jupiter! Piqued, repiqued, slammed, and capotted!” He once more mopped his eyes with the Belcher handkerchief. “You’ll have to buy me that pair of colours, Ricky: damme, you owe it to me, for I told you to run, now, didn’t I?”

“But he did not run!” Pen said anxiously. “It was I who ran. Richard didn’t.”

“Oh yes, I did!” said Sir Richard taking snuff.

“No, no, you know you only came to take care of me; you said I could not go alone!”

Cedric looked at her in a puzzled way. “Y’know, I can’t make this out at all! If you only met three nights ago, you can’t be eloping!”

“Of course we’re not eloping! I came here on—on a private matter, and Richard pretended to be my tutor. There is not a question of eloping!”

“Tutor? Lord! I thought you said he was your cousin?”

“My dear Cedric, do try not to be so hidebound!” begged Sir Richard. “I have figured as a tutor, an uncle, a trustee, and a cousin.”

“You seem to me to be a sad romp!” Cedric told Pen severely. “How old are you?”

“I am seventeen, but I do not see that it is any concern of yours.”

“Seventeen!” Cedric cast a dismayed glance at Sir Richard. “Ricky, you madman! You’re in the basket now, the pair of you! And what your mother and Louisa will say, let alone that sour-faced sister of mine—! When is the wedding?”

“That,” said Sir Richard, “is the point we were discussing when you walked in on us.”

“Better get married quietly somewhere where you ain’t known. You know what people are!” Cedric said, wagging his head. “Damme, if I won’t be best man!”

“Well, you won’t,” said Pen, flushing. “We are not going to be married. It is quite absurd to think of such a thing.”

“I know it’s absurd,” replied Cedric frankly. “But you should have thought of that before you started jauntering about the country in this crazy fashion. There’s nothing for it now: you’ll have to be married!”

“I won’t!” Pen declared. “No one need ever know that I am not a boy, except you, and one other, who doesn’t signify.”

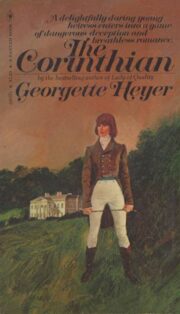

"The Corinthian" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Corinthian". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Corinthian" друзьям в соцсетях.