“Well, I don’t think he meant it to be a compliment,” said Pen doubtfully.

He smiled but said nothing. The waiter came back into the room with a laden tray, and began to set various dishes on the table. When he had withdrawn, Sir Richard pulled a chair out for Pen, and said: “You are served, brat. Hungry?”

“Not very,” she replied, sitting down.

He moved to his own place. “Why, how is this?”

“Well, I don’t know. Piers is going to elope with Lydia at midnight.”

“I trust that circumstance has not taken away your appetite?”

“Oh no! I think they will deal famously together, for they are both very silly.”

“True. What had you to do with their elopement?”

“Oh, very little, I assure you, sir! Lydia made up her mind to do it without any urging from me. All I did was to hire the post-chaise for Piers, on account of his being well-known in Keynsham.”

“I suppose that means that we shall be obliged to sustain another visit from Major Daubenay. I seem to be plunging deeper and deeper into a life of crime.”

She looked up enquiringly. “Why, sir? You have done nothing!”

“I am aware. But I undoubtedly should do something.”

“Oh no, it is all arranged! There is truly nothing left to do.”

“You don’t think that I—as one having reached years of discretion—might perhaps be expected to nip this shocking affair in the bud?”

“Tell the Major, do you mean?” Pen cried. “Oh, Richard, you would not do such a cruel thing? I am persuaded you could not!”

He refilled his glass. “I could, very easily, but I won’t. I am not, to tell you the truth, much interested in the affairs of a pair of lovers whom I have found, from the outset, extremely tiresome. Shall we discuss instead our own affairs?”

“Yes, I think we ought to,” she agreed. “I have been so busy to-day I had almost forgot the stammering-man. I do trust, Richard, we shall not be arrested!”

“Indeed, so do I!” he said, laughing.

“It’s very well to laugh, but I could see that Mr Philips did not like us at all.”

“I fear that your activities disarranged his mind. Fortunately, news has reached him that a man whom I suspect of being none other than the egregious Captain Trimble has been taken up by the authorities in Bath.”

“Good gracious, I never thought he would be caught! Pray, had he the necklace?”

“That, I am as yet unable to tell you. It is to be hoped that Luttrell and his bride will not prolong their honeymoon, since I fancy Lydia will be wanted to identify the prisoner.”

“If she knew that, I dare say she would never come back at all,” said Pen.

“A public-spirited female,” commented Sir Richard.

She giggled. “She has no spirit at all. I told you so, sir! Will the—the authorities wish to see me?”

“I hardly think so. In any event, they are not going to see you.”

“No, I must say I feel it might be excessively awkward if I were forced to appear,” remarked Pen. “In fact, sir, I think—I think I had better go home, don’t you?”

He looked at her. “To your Aunt Almeria, brat?”

“Yes, of course. There is nowhere else for me to go.”

“And Cousin Fred?”

“Well, I hope that after all the adventures I have gone through he will not want to marry me any more,” said Pen optimistically. “He is very easily shocked, you know.”

“Such a man would not be at all the husband for you,” he said, shaking his head. “You must undoubtedly choose some one who is not at all easily shocked.”

“Perhaps I had better mend my ways,” said Pen, with a swift unhappy smile.

“That would be a pity, for your ways are delightful. I have a better plan than yours, Pen.”

She got up quickly from the table. “No, no! Please no, sir!” she said in a choking voice.

He too rose, and held out his hand. “Why do you say that? I want you to marry me, Pen.”

“Oh Richard, I wish you would not!” she begged, retreating to the window. “Indeed, I don’t want you to offer for me. It is extremely obliging of you, but I could not!”

“Obliging of me! What nonsense is this?”

“Yes, yes, I know why you have said it!” she said distressfully. “You feel that you have compromised me, but indeed you haven’t, for no one will ever know the truth!”

“I detect the fell hand of Mr Luttrell,” said Sir Richard rather grimly. “What pernicious rubbish has he been putting into your head, my little one?”

This term of endearment made Pen wink away a sudden tear. “Oh no! Only I was stupid not to think of it before. Really, I have no more sense than Lydia! But you are so much older than I am that it truly did not occur to me—until Piers came, and that you told him, to save my face, that we were betrothed! Then I saw what a little fool I had been! But it does not signify, sir, for Piers will never breathe a word, even to Lydia, and Aunt Almeria need not know that I have been with you all the time.”

“Pen, will you stop talking nonsense? I am not in the least chivalrous, my dear: you may ask my sister, and she will tell you that I am the most selfish creature alive. I never do anything to please anyone but myself.”

“That I know to be untrue!” Pen said. “If your sister thinks it, she doesn’t know you. And I am not talking nonsense. Piers was shocked to find me with you, and you did think he had reason, or you would not have said what you did.”

“Oh yes!” he responded. “I am well aware of what the world would think of this escapade, but, believe me, my little love, I don’t offer marriage from motives of chivalry. To be plain with you, I started on this adventure because I was drunk, and because I was bored, and because I thought I had to do something which was distasteful to me. I stayed in it because I found myself enjoying it as I have not enjoyed anything for years.”

“You did not enjoy the stage-coach,” she reminded him.

“No, but we need not make a practice of travelling by the stage-coach, need we?” he said, smiling down at her. “Briefly, Pen, when I met you I was about to contract a marriage of convenience. Within twelve hours of making your acquaintance, I knew that no matter what might happen, I would not contract that marriage. Within twenty-four hours, my dear, I knew that I had found what I had come to believe did not exist’

“What was that?” she asked shyly.

His smile was a little twisted. “A woman—no, a chit of a girl! An impertinent, atrocious, audacious brat—whom I am very sure I cannot live without.”

“Oh!” said Pen, blushing furiously. “How kind of you to say that to me! I know just why you do, and indeed I am very grateful to you for putting it so prettily!”

“And you don’t believe a word of it!”

“No, for I am very sure you would not have thought of marrying me if Piers had not been in love with Lydia Daubenay,” she said simply. “You are sorry for me, because of that, and so—”

“Not in the least.”

“I think you are a little, Richard. And I quite see that to a person like you—for it is no use to pretend to me that you are selfish, because I know that you are nothing of the sort—to a person like you, it must seem that you are bound in honour to marry me. Now, confess! That is true, is it not? Don’t—please don’t tell me polite lies!”

“Very well,” he replied. “It is true that having embroiled you in this situation I ought in honour to offer you the protection of my name. But I am offering you my heart, Pen.”

She searched feverishly for her handkerchief, and mopped her brimming eyes with it. “Oh, I do thank you!” she said in a muffled voice. “You have such beautiful manners, sir!”

“Pen, you impossible child!” he exclaimed. “I am trying to tell you that I love you, and all you will say is that I have beautiful manners!”

“You cannot fall in love with a person in three days!” she objected.

He had taken a step towards her, but he checked himself at that. “I see.”

She gave her eyes a final wipe, and said apologetically: “I beg your pardon! I didn’t mean to cry, only I think I am a little tired, besides having had a shock on account of Piers, you know.”

Sir Richard, who had been intimately acquainted with many women, thought that he did know. “I was afraid of that,” he said. “Did you care so much, Pen?”

“No, but I thought I did, and it is all very lowering, if you understand what I mean, sir.”

“I suppose I do. I am too old for you, am I not?”

“I am too young for you,” said Pen unsteadily. “I dare say you think I am amusing—in fact, I know you do, for you are for ever laughing at me—but you would very soon grow tired of laughing, and—and perhaps be sorry that you had married me.”

“I am never tired of laughing.”

“Please do not say any more!” she implored. “It has been such a splendid adventure until Piers came, and forced you to say what you did! I—I would rather that you didn’t say any more, Richard, if you please!”

He perceived that his careful strategy in allowing her to meet her old playfellow before declaring himself had been mistaken. There did not seem to be any way of explaining this. No doubt, he thought, she had from the outset regarded him in an avuncular light. He wondered how deeply her affections had been rooted in the dream-figure of Piers Luttrell, and, misreading her tears, feared that her heart had indeed suffered a severe wound. He wanted very much to catch her up in his arms, overbearing her resistance and her scruples, but her very trust in him set up a barrier between them. He said, with a shadow of a smile: “I have given myself a hard task, have I not?”

She did not understand him, and so said nothing. Not until Piers had shown her a shocked face, and Sir Richard had claimed her as his prospective wife, had she questioned her own heart. Sir Richard had been merely her delightful travelling companion, an immensely superior personage on whom one could place one’s dependence. The object of her journey had obsessed her thoughts to such a degree that she had never paused to ask herself whether the entrance into her life of a Corinthian had not altered the whole complexion of her adventure. But it had; and when she had encountered Piers, it had been suddenly borne in upon her that she did not care two pins for him. The Corinthian had ousted him from her mind and heart. Then Piers had turned the adventure into a faintly sordid intrigue, and Sir Richard had made his declaration, not because he had wanted to (for if he had, why should he have held his tongue till then?) but because honour had forced the words out of him. It was absurd to think that a man of fashion, nearing his thirtieth year, could have fallen head-over-ears in love with a miss scarcely out of the schoolroom, however easily the miss might have tumbled into love with him.

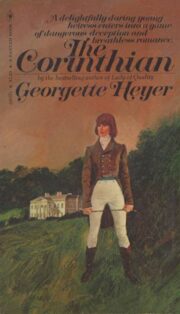

"The Corinthian" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Corinthian". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Corinthian" друзьям в соцсетях.