“Nonsense!” said Louisa. “It is understood, of course, that Richard would make handsome settlements. But as for his being responsible for Cedric’s and Beverley’s debts, I’m sure I know of no reason why he should!”

“You comfort me, Louisa,” said Sir Richard.

She looked up at him not unaffectionately. “Well, I think it is time to be frank, Richard. People will be saying next that you are playing fast and loose with Melissa, for you must know the understanding between you is an open secret. If you had chosen to marry someone else, five, ten years ago, it would have been a different thing. But so far as I am aware your affections have never even been engaged, and here you are, close on thirty, as good as pledged to Melissa Brandon, and nothing settled!”

Lady Wyndham, though in the fullest agreement with her daughter, was moved at this point to defend her son, which she did by reminding Louisa that Richard was only twenty-nine after all.

“Mama, Richard will be thirty in less than six months. For I,” said Louisa with resolution, “am turned thirty-one.”

“Louisa, I am touched!” said Sir Richard. “Only the deepest sisterly devotion, I am persuaded, could have wrung from you such an admission.”

She could not repress a smile, but said with as much severity as she could muster: “It is no laughing matter. You are no longer in your first youth, and you know as well as I do that it is your duty to think seriously of marriage.”

“Strange,” mused Sir Richard, “that one’s duty should be invariably so disagreeable.”

“I know,” said George, heaving a sigh. “Very true! very true indeed!”

“Pooh! nonsense! What a coil you make of a simple matter!” Louisa said. “Now, if I were to press you to marry some romantical miss, always wanting you to make love to her, and crying her eyes out every time you chose to seek your amusements out of her company, you might have reason to complain. But Melissa—yes, an iceberg, George, if you like, and what else, pray, is Richard?—Melissa, I say, will never plague you in that way.”

Sir Richard’s eyes dwelled inscrutably upon her face for a moment. Then he moved to the table and poured himself out another glass of Madeira.

Louisa said defensively: “Well, you don’t wish her to cling about your neck, I suppose?”

“Not at all.”

“And you are not in love with any other woman, are you?”

“I am not.”

“Very well, then! To be sure, if you were in the habit of falling in and out of love, it would be a different matter. But, to be plain with you, you are the coldest, most indifferent, selfish creature alive, Richard, and you will find in Melissa an admirable partner.”

Inarticulate clucking sounds from George, indicative of protest, caused Sir Richard to wave a hand towards the Madeira. “Help yourself, George, help yourself!”

“I must say, I think it most unkind in you to speak to your brother like that,” said Lady Wyndham. “Not but what you are selfish, dear Richard. I’m sure I have said so over and over again. But so it is with the greater part of the world! Everywhere one turns one meets with nothing but ingratitude!”

“If I have done Richard an injustice, I will willingly ask his pardon,” said Louisa.

“Very handsomely said, my dear sister. You have done me no injustice. I wish you will not look so distressed, George: your pity is quite wasted on me, I assure you. Tell me, Louisa: have you reason to suppose that Melissa expects me to—er—pay my addresses to her?”

“Certainly I have. She has been expecting it any time these five years!”

Sir Richard looked a little startled. “Poor girl!” he said. “I must have been remarkably obtuse.”

His mother and sister exchanged glances. “Does that mean that you will think seriously of marriage?” asked Louisa.

He looked thoughtfully down at her. “I suppose it must come to that.”

“Well, for my part,” said George, defying his wife, “I would look around me for some other eligible female! Lord, there are dozens of ’em littering town! Why, I’ve seen I don’t know how many setting their caps at you! Pretty ones, too, but you never notice them, you ungrateful dog!”

“Oh yes, I do,” said Sir Richard, with a curl of the lips.

“Must George be vulgar?” asked Lady Wyndham tragically.

“Be quiet, George! And as for you, Richard, I consider it in the highest degree nonsensical for you to take up that attitude. There is no denying that you’re the biggest catch on the Marriage Mart—Yes, Mama, that is vulgar too, and I beg your pardon—but you have a lower opinion of yourself than I credit you with if you can suppose that your fortune is the only thing about you which makes you a desirable parti. You are generally accounted handsome—indeed, no one, I believe, could deny that your person is such as must please; and when you will take the trouble to be conciliating there is nothing in your manners to disgust the nicest taste.”

“This encomium, Louisa, almost unmans me,” said Sir Richard, much moved.

“I am perfectly serious. I was about to add that you often spoil everything by your odd humours. I do not know how you should expect to engage a female’s affection when you never bestow the least distinguishing notice upon any woman! I do not say that you are uncivil, but there is a languor, a reserve in your manner, which must repel a woman of sensibility.”

“I am a hopeless case indeed,” said Sir Richard.

“If you want to know what I think, which I do not suppose you do, so you need not tell me so, it is that you are spoilt, Richard. You have too much money, you have done everything you wished to do before you are out of your twenties; you have been courted by match-making Mamas, fawned on by toadies, and indulged by all the world. The end of it is that you are bored to death. There! I have said it, and though you may not thank me for it, you will admit that I am right.”

“Quite right,” agreed Sir Richard. “Hideously right, Louisa!”

She got up. “Well, I advise you to get married and settle down. Come, Mama! We have said all we meant to say, and you know we are to call in Brook Street on our way home. George, do you mean to come with, us?”

“No,” said George. “Not to call in Brook Street, I daresay I shall stroll up to White’s presently.”

“Just as you please, my love,” said Louisa, drawing on her gloves again.

When the ladies had been escorted to the waiting barouche, George did not at once set out for his club, but accompanied his brother-in-law back into the house. He preserved a sympathetic silence until they were out of ear-shot of the servants, but caught Sir Richard’s eye then, in a very pregnant look, and uttered the one word: “Women!”

“Quite so,” said Sir Richard.

“Do you know what I’d do if I were you, my boy?”

“Yes,” said Sir Richard.

George was disconcerted. “Damn it, you can’t know!”

“You would do precisely what I shall do.”

“What’s that?”

“Oh—offer for Melissa Brandon, of course,” said Sir Richard.

“Well, I wouldn’t,” said George positively. “I wouldn’t marry Melissa Brandon for fifty sisters! I’d find a cosier armful, ’pon my soul I would!”

“The cosiest armful of my acquaintance was never so cosy as when she wanted to see my purse-strings untied,” said Sir Richard cynically.

George shook his head. “Bad, very bad! I must say, it’s enough to sour any man. But Louisa’s right, you know: you ought to get married. Won’t do to let the name die out.” An idea occurred to him. “You wouldn’t care to put it about that you’d lost all your money, I suppose?”

“No,” said Sir Richard, “I wouldn’t.”

“I read somewhere of a fellow who went off to some place where he wasn’t known. Devil of a fellow he was: some kind of a foreign Count, I think. I don’t remember precisely, but there was a girl in it, who fell in love with him for his own sake.”

“There would be,” said Sir Richard.

“You don’t like it?” George rubbed his nose, a little crestfallen. “Well, damme if I know what to suggest!”

He was still pondering the matter when the butler announced Mr Wyndham, and a large, portly, and convivial-looking gentleman rolled into the room, ejaculating cheerfully: “Hallo, George! You here? Ricky, my boy, your mother’s been at me again, confound her! Made me promise I’d come round to see you, though what the devil she thinks I can do is beyond me!”

“Spare me!” said Sir Richard wearily. “I have already sustained a visit from my mother, not to mention Louisa.”

“Well, I’m sorry for you, my boy, and if you take my advice you’ll marry that Brandon-wench, and be done with it. What’s that you have there? Madeira? I’ll take a glass.”

Sir Richard gave him one. He lowered his bulk into a large armchair, stretched his legs out before him, and raised the glass. “Here’s a health to the bridegroom!” he said, with a chuckle. “Don’t look so glum, nevvy! Think of the joy you’ll be bringing into Saar’s life!”

“Damn you,” said Sir Richard. “If you had ever had a shred of proper feeling, Lucius, you would have got married fifty years ago, and reared a pack of brats in your image. A horrible thought, I admit, but at least I should not now be cast for the role of Family Sacrifice.”

“Fifty years ago,” retorted his uncle, quite unmoved by these insults, “I was only just breeched. This is a very tolerable wine, Ricky. By the way, they tell me young Beverley Brandon’s badly dipped. You’ll be a damned public benefactor if you marry that girl. Better let your lawyer attend to the settlements, though. I’d be willing to lay you a monkey Saar tries to bleed you white. What’s the matter with you, George? Got the toothache?”

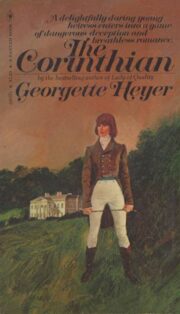

"The Corinthian" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Corinthian". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Corinthian" друзьям в соцсетях.