“Richard thinks they all want him for his money,” ventured George.

“I dare say they may. What has that to say to anything, pray? I imagine you do not mean to tell me that Richard is romantic!”

No, George was forced to admit that Richard was not romantic.

“If I live to see him suitably married, I can die content!” said Lady Wyndham, who had every expectation of living for another thirty years. “His present course fills my poor mother’s heart with foreboding!”

Loyalty forced George to expostulate. “No, really, ma’am! Really, I say! There’s no harm in Richard, not the least in the world, ’pon my honour!”

“He puts me out of all patience!” said Louisa. “I love him dearly, but I despise him with all my heart! Yes, I do, and I do not care who hears me say so! He cares for nothing but the set of his cravat, the polish on his boots, and the blending of his snuff!”

“His horses!” begged George unhappily. “Oh, his horses! Very well! Let us admit him to be a famous whip! He beat Sir John Lade in their race to Brighton! A fine achievement indeed!”

“Very handy with his fives!” gasped George, sinking but game.

“You may admire a man for frequenting Jackson’s Saloon, and Cribb’s Parlour! I do not!”

“No, my love,” George said. “No, indeed, my love!”

“And I make no doubt you see nothing reprehensible in his addiction to the gaming-table! But I had it on the most excellent authority that he dropped three thousand pounds at one sitting at Almack’s!”

Lady Wyndham moaned, and dabbed at her eyes. “Oh, do not say so!”

“Yes, but he’s so devilish wealthy it can’t signify!” said George.

“Marriage,” said Louisa, “will put a stop to such fripperies.”

The depressing picture this dictum conjured up reduced George to silence. Lady Wyndham said, in a voice dark with mystery: “Only a mother could appreciate my anxieties. He is at a dangerous age, and I live from day to day in dread of what he may do!”

George opened his mouth, encountered a look from his wife, shut it again, and tugged unhappily at his cravat.

The door opened; a Corinthian stood upon the threshold, cynically observing his relatives. “A thousand apologies,” said the Corinthian, bored but polite. “Your very obedient servant, ma’am. Louisa, yours! My poor George! Ah—was I expecting you?”

“Apparently not!” retorted Louisa, bristling.

“No, you weren’t. I mean, they took it into their heads—I couldn’t stop them!” said George heroically.

“I thought I was not,” said the Corinthian, closing the door, and advancing into the room. “But my memory, you know, my lamentable memory!”

George, running an experienced eye over his brother-in-law, felt his soul stir. “B’gad, Richard, I like that! That’s a devilish well-cut coat, ’pon my honour, it is! Who made it?”

Sir Richard lifted an arm, and glanced at his cuff. “Weston, George, only Weston.”

“George!” said Louisa awfully.

Sir Richard smiled faintly, and crossed the room to his mother’s side. She held out her hand to him, and he bowed over it with languid grace, just brushing it with his lips. “A thousand apologies, ma’am!” he repeated. “I trust my people have looked after you—er—all of you?” His lazy glance swept the room. “Dear me!” he said. “George, you are near to it: oblige me, my dear fellow, by pulling the bell!”

“We do not need any refreshment, I thank you, Richard,” said Louisa.

The faint, sweet smile silenced her as none of her husband’s expostulations had ever done. “My dear Louisa, you mistake—I assure you, you mistake! George is in the most urgent need of—er—stimulant. Yes, Jeffries, I rang. The Madeira—oh, ah! and some ratafia, Jeffries, if you please!”

“Richard, that’s the best Waterfall I’ve ever seen!” exclaimed George, his admiring gaze fixed on the intricate arrangement of the Corinthian’s cravat.

“You flatter me, George; I fear you flatter me.”

“Pshaw!” snapped Louisa.

“Precisely, my dear Louisa,” agreed Sir Richard amiably.

“Do not try to provoke me, Richard!” said Louisa, on a warning note. “I will allow your appearance to be everything that it should be—admirable, I am sure!”

“One does one’s poor best,” murmured Sir Richard.

Her bosom swelled. “Richard, I could hit you!” she declared.

The smile grew, allowing her a glimpse of excellent white teeth. “I don’t think you could, my dear.”

George so far forgot himself as to laugh. A quelling glance was directed upon him. “George, be quiet!” said Louisa.

“I must say,” conceded Lady Wyndham, whose maternal pride could not be quite overborne, “there is no one, except Mr Brummell, of course, who looks as well as you do, Richard.”

He bowed, but he did not seem to be unduly elated by this encomium. Possibly he took it as his due. He was a very notable Corinthian. From his Wind-swept hair (most difficult of all styles to achieve), to the toes of his gleaming Hessians, he might have posed as an advertisement for the Man of Fashion. His fine shoulders set off a coat of superfine cloth to perfection; his cravat, which had excited George’s admiration, had been arranged by the hands of a master; his waistcoat was chosen with a nice eye; his biscuit-coloured pantaloons showed not one crease; and his Hessians with their jaunty gold tassels, had not only been made for him by Hoby, but were polished, George suspected, with a blacking mixed with champagne. A quizzing-glass on a black ribbon hung round his neck; a fob at his waist; and in one hand he carried a Sevres snuff-box. His air proclaimed his unutterable boredom, but no tailoring, no amount of studied nonchalance, could conceal the muscle in his thighs, or the strength of his shoulders. Above the starched points of his shirt-collar, a weary, handsome face showed its owner’s disillusionment. Heavy lids drooped over grey eyes which were intelligent enough, but only to observe the vanities of the world; the smile which just touched that resolute mouth seemed to mock the follies of Sir Richard’s fellow men.

Jeffries came back into the room with a tray, and set it upon a table. Louisa waved aside the offer of refreshment, but Lady Wyndham accepted it, and George, emboldened, by his mother-in-law’s weakness, took a glass of Madeira.

“I dare say,” said Louisa, “that you are wondering what we are here for.”

“I never waste my time in idle speculation,” replied Sir Richard gently. “I feel sure that you are going to tell me what you are here for.”

“Mama and I have come to speak to you about your marriage,” said Louisa, taking the plunge.

“And what,” enquired Sir Richard, “has George come to speak to me about?”

“That too, of course!”

“No, I haven’t!” disclaimed George hurriedly. “You know I said I’d have nothing to do with it! I never wanted to come at all!”

“Have some more Madeira,” said Sir Richard soothingly.

“Well, thank you, yes, I will. But don’t think I’m here to badger you about something which don’t concern me, because I’m not!”

“Richard!” said Lady Wyndham deeply, “I dare no longer meet Saar face to face!”

“As bad as that, is he?” said Sir Richard. “I haven’t seen him myself these past few weeks, but I’m not at all surprised. I fancy I heard something about it, from someone—I forget whom. Taken to brandy, hasn’t he?”

“Sometimes,” said Lady Wyndham, “I think you are utterly devoid of sensibility!”

“He is merely trying to provoke you, Mama. You know perfectly well what Mama means, Richard. When do you mean to offer for Melissa?”

There was a slight pause. Sir Richard set down his empty wine-glass, and flicked with one long finger the petals of a flower in a bowl on the table. “This year, next year, sometime—or never, my dear Louisa.”

“I am very sure she considers herself as good as plighted to you,” Louisa said.

Sir Richard was looking down at the flower under his hand, but at this he raised his eyes to his sister’s face, in an oddly keen, swift look. “Is that so?”

“How should it be otherwise? You know very well that Papa and Lord Saar designed it so years ago.”

The lids veiled his eyes again. “How medieval of you!” sighed Sir Richard.

“Now, don’t, pray, take me up wrongly, Richard! If you don’t like Melissa, there is no more to be said. But you do like her—or if you don’t, at least I never heard you say so! What Mama and I feel—and George, too—is that it is time and more that you were settled in life.”

A pained glanced reproached Lord Trevor. “Et tu, Brute?” said Sir Richard.

“I swear I never said so!” declared George, choking over his Madeira. “It was all Louisa. I dare say I may have agreed with her. You know how it is, Richard!”

“I know,” agreed Sir Richard, sighing. “You too, Mama?”

“Oh Richard, I live only to see you happily married, with your children about you!” said Lady Wyndham, in trembling tones.

A slight, unmistakable shudder ran through the Corinthian. “My children about me ... Yes. Precisely, ma’am. Pray continue!”

“You owe it to the name,” pursued his mother. “You are the last of the Wyndhams, for it’s not to be supposed that your Uncle Lucius will marry at this late date. There is Melissa, dear girl, the very wife for you! So handsome, so distinguished—birth, breeding: everything of the most desirable!”

“Ah—your pardon, ma’am, but do you include Saar, and Cedric, not to mention Beverley, under that heading?”

“That’s exactly what I say!” broke in George. “ “It’s all very well,” I said, “and if a man likes to marry an iceberg it’s all one to me, but you can’t call Saar a desirable father-in-law, damme if you can! While as for the girl’s precious brothers,” I said, “they’ll ruin Richard inside a year!”“

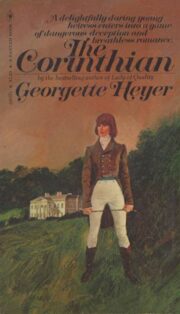

"The Corinthian" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Corinthian". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Corinthian" друзьям в соцсетях.