No one but Miss Winwood was inclined to indulge in such questionings, least of all Lady Winwood, basking in the envy of her acquaintance. Everyone was anxious to felicitate her; everyone knew what a triumph was hers. Even Mr Walpole, who was staying in Arlington Street at the time, came to pay her a morning visit, and to glean a few details. Mr Walpole’s face wore an approving smile, though he regretted that his god-daughter should be marrying a Tory. But then Mr Walpole was so very earnest a Whig, and even he seemed to think that Lady Winwood was right to disregard Rule’s political opinions. He set the tips of his fingers together, crossing one dove-silk stockinged leg over the other, and listened with his well-bred air to all Lady Winwood had to say. She had a great value for Mr Walpole, whom she had known for many years, but she was careful in what she told him. No one had a kinder heart than this thin, percipient gentleman, but he had a sharp nose for a morsel of scandal, and a satiric pen. Let him but get wind of Horatia’s escapade, and my Lady Ossory and my Lady Aylesbury would have the story by the next post.

Fortunately, the rumour of Rule’s offer for Elizabeth had not reached Twickenham, and beyond wondering that Lady Winwood should care to see Horatia married before the divine Elizabeth (who was quite his favourite), he said nothing to put an anxious mother on her guard. So Lady Winwood told him confidentially that, although nothing was yet to be declared, Elizabeth too was to leave the nest. Mr Walpole was all interest, but pursed his lips a little when he heard about Mr Edward Heron. To be sure, of good family (trust Mr Walpole to know that!), but he could have wished for someone of greater consequence for his little Lizzie. Mr Walpole did so like to see his young friends make good matches. Indeed, his satisfaction at Horatia’s betrothal made him forget a certain disastrous day at Twickenham when Horatia had shown herself quite unworthy of having the glories of his little Gothic Castle exhibited to her, and he patted her hand, and said that she must come and drink a syllabub at Strawberry quite soon. Horatia, under oath not to be farouche (“for he may be rising sixty, my love, and live secluded, but there’s no one whose good opinion counts for more’), thanked him demurely, and hoped that she would not be expected to admire and fondle his horrid little dog, Rosette, who was odiously spoiled, and yapped at one’s heels.

Mr Walpole said that she was very young to contemplate matrimony, and Lady Winwood sighed that alas, it was true: she was losing her darling before she had even been to Court.

That was an unwise remark, because it gave Mr Walpole an opportunity for recounting, as he was very fond of doing, how his father had taken him to kiss George the First’s hand when he was a child. Horatia slipped out while he was in the middle of his anecdote, leaving her Mama to assume an expression of spurious interest.

In quite another quarter, though topographically hardly a stone’s throw from South Street, the news of Rule’s betrothal created different sensations. There was a slim house in Hertford Street where a handsome widow held her court, but it was not at all the sort of establishment that Lady Winwood visited. Caroline Massey, relict of a wealthy tradesman, had achieved her position in the Polite World by dint of burying the late Sir Thomas’s connexion with the City in decent oblivion, and relying upon her own respectable birth and very considerable good looks. Sir Thomas’s fortune, though so discreditably acquired, was also useful. It enabled his widow to live in a very pretty house in the best part of town, to entertain in a lavish and agreeable fashion, and to procure the sponsorship of a Patroness who was easy-going enough to introduce her into Society. The offices of this Patroness had long ceased to be necessary to Lady Massey. In some way, best known (said various indignant ladies) to herself, she had contrived to become a Personage. One was for ever meeting her, and if a few doors remained obstinately closed against her, she had a sufficient following for this not to signify. That the following consisted largely of men was not likely to trouble her; she was not a woman who craved female companionship, though a faded and resigned lady, who was believed to be her cousin, constantly resided with her. Miss Janet’s presence was a sop thrown to the conventions. Yet, to do them justice, it was not Lady Massey’s morals that stuck in the gullets of certain aristocratic dames. Everyone had their own affaires, and if gossip whispered of intimacies between the fair Massey and Lord Rule, as long as the lady conducted her amorous passages with discretion only such rigid moralists as Lady Winwood would throw up hands of horror. It was the fatal taint of the City that would always exclude Lady Massey from the innermost circle of Fashion. She was not bon ton. It was said without rancour, even with a pitying shrug of well-bred shoulders, but it was damning. Lady Massey, aware of it, never betrayed by word or look that she was conscious of that almost indefinable bar, and not even the resigned cousin knew that to become one of the Select was almost an obsession with her.

There was only one person who guessed, and he seemed to derive a certain sardonic amusement from it. Robert, Baron Lethbridge, could usually derive amusement from the frailty of his fellows.

Upon an evening two days after the Earl of Rule’s second visit to the Winwood establishment, Lady Massey held a card-party in Hertford Street. These parties were always well attended, for one might be sure of deep play, and a charming hostess, whose cellar (thanks to the ungenteel but knowledgeable Sir Thomas) was excellently stocked.

The saloon upon the first floor was a charming apartment, and set off its mistress to advantage. She had lately purchased some very pretty pieces of gilt furniture in Paris, and had had all her old hangings pulled down, and new ones of straw-coloured silk put in their place, so that the room, which had before been rose-pink, now glowed palely yellow. She herself wore a gown of silk brocade with great panniers, and an underskirt looped with embroidered garlands. Her hair was dressed high in a pouf au sentiment, with curled feathers for which she had paid fifty louis apiece at Bertin’s, and scented roses, placed artlessly here and there in the powdered erection. This coiffure had been the object of several aspiring ladies’ envy, and had put Mrs Montague-Damer quite out of countenance. She too had acquired a French fashion, and had expected to have it much admired. But the exquisite pouf au sentiment made her own chien couchant look rather ridiculous, and quite spoiled her evening’s enjoyment.

The gathering in the saloon was a modish one; dowdy persons had no place in Lady Massey’s house, though she could welcome such freaks as the Lady Amelia Pridham, that grossly fat and free-spoken dame in the blonde satin who was even now arranging her rouleaus in front of her. There were those who wondered that the Lady Amelia should care to visit in Hertford Street, but the Lady Amelia, besides being of an extreme good nature, would go to any house where she could be sure of deep basset.

Basset was the game of the evening, and some fifteen people were seated at the big round table. It was when Lord Lethbridge held the bank that he chose to make his startling announcement. As he paid on the couch he said with a faintly malicious note in his voice: “I don’t see Rule tonight. No doubt the bridegroom-elect dances attendance in South Street.”

Opposite him, Lady Massey quickly looked up from the cards in front of her, but she did not say anything.

A Macaroni, with an enormous ladder-toupet covered in blue hair-powder, and a thin, unhealthily sallow countenance, cried out: “What’s that?”

Lord Lethbridge’s hard hazel eyes lingered for a moment on Lady Massey’s face. Then he turned slightly to look at the startled Macaroni. He said smilingly: “Do you tell me I am before you with the news, Crosby? I thought you of all people must have known.” His satin-clad arm lay on the table, the pack of cards clasped in his white hand. The light of the candles in the huge chandelier over the table caught the jewels in the lace at his throat, and made his eyes glitter queerly.

“What are you talking about?” demanded the Macaroni, half rising from his seat.

“But Rule, my dear Crosby!” said Lethbridge. “Your cousin Rule, you know.”

“What of Rule?” inquired the Lady Amelia, regretfully pushing one of her rouleaus across the table.

Lethbridge’s glance flickered to Lady Massey’s face again.

“Why, only that he is about to enter the married state,” he replied.

There was a stir of interest. Someone said “Good God, I thought he was safe to stay single! Well, upon my soul! Who’s the fortunate fair one, Lethbridge?”

“The fortunate fair one is the youngest Miss Winwood,” said Lethbridge. “A romance, you perceive. I believe she is not out of the schoolroom.”

The Macaroni, Mr Crosby Drelincourt, mechanically straightened the preposterous bow he wore in place of a cravat. “Pho, it is a tale!” he said uneasily. “Where had you it?”

Lethbridge raised his thin, rather slanting brows. “Oh, I had it from the little Maulfrey. It will be in the Gazette by tomorrow.”

“Well, it’s very interesting,” said a portly gentleman in claret velvet, “but the game, Lethbridge, the game!”

“The game,” bowed his lordship, and sent a glance round at the cards on the table.

Lady Massey, who had won the couch, suddenly put out her hand and nicked the corner of the Queen that lay before her. “Paroli!” she said in a quick, unsteady voice.

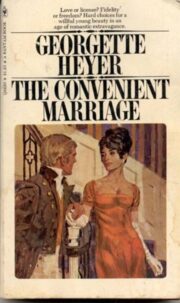

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.