Rule took his hand and gripped it. “The only thing that ever made you tolerable, my dear Robert, was your impudence. I shall be in town tomorrow. I’ll send him down to you. Good night.”

Half an hour later he strolled into the library at Meering, where Mr Gisborne sat reading a newspaper, and stretched himself on the couch with a long sigh of content.

Mr Gisborne looked at him sideways, wondering. The Earl had clasped his hands behind his head, and where the lace ruffle fell back from his right wrist the corner of a bloodstained handkerchief showed. The lazy eyelids lifted. “Dear Arnold, I am afraid you will be disappointed in me again. I hardly dare tell you but we are going back to London to-morrow.”

Mr Gisborne met those twinkling eyes and bowed slightly. “Very well, sir,” he said.

“You are—yes, positively you are—a prince of secretaries, Arnold,” said his lordship. “And you are quite right, of course. How do you contrive to be so acute?”

Mr Gisborne smiled. “There’s a handkerchief round your forearm, sir,” he pointed out.

The Earl drew the arm from behind his head and regarded it pensively. “That,” he said, “was a piece of sheer carelessness. I must be growing old.” With which he closed his eyes and relapsed into a state of agreeable coma.

Chapter Eighteen

Sir Roland Pommeroy, returning empty-handed from his mission, found Horatia and her brother playing piquet together in the saloon. For once Horatia’s mind was not wholly concentrated on her cards, for no sooner was Sir Richard ushered in than she threw down her hand and turned eagerly towards him. “Have you g-got it?”

“Here, are you going to play this game, or not?” said the Viscount, more single-minded than his sister.

“No, of c-course not. Sir Roland, did he give it to you?”

Sir Roland waited carefully until the door was shut behind the footman and coughed. “Must warn you, ma’am—greatest caution needed before the servants. Affair to be hushed up—won’t do if it gets about.”

“Never mind about that,” said the Viscount impatiently. “Never had a servant yet who did not know all my secrets. Have you got the brooch?”

“No,” replied Sir Roland. “Deeply regret, ma’am, but Lord Lethbridge denies all knowledge.”

“B-but I know it’s there!” insisted Horatia. “You d-didn’t tell him it was mine, d-did you?”

“Certainly not, ma’am. Thought it all out on my way. Told him the brooch belonged to my great-aunt.”

The Viscount, who had been absently shuffling the pack, put the cards down at this. “Told him it belonged to your great-aunt?” he repeated. “Burn it, even if the fellow was knocked out, you’ll never get him to believe your great-aunt came tottering into his house at two in the morning! “Taint’ reasonable. What’s more, if he did believe it, you oughtn’t to set a tale like that going about your great-aunt.”

“My great-aunt is dead,” said Sir Roland with some sever-ity.”

“Well, that makes it worse,” said the Viscount. “You can’t expect a man like Lethbridge to listen to ghost stories.”

“Nothing to do with ghosts!” replied Sir Roland, nettled. “You’re not yourself, Pel. Told him it was a bequest.”

“B-but it’s a lady’s brooch!” said Horatia. “He c-can’t have believed you!”

“Oh, your pardon, ma’am, but indeed! Plausible story—told easily—nothing simpler. Unfortunately, not in his lordship’s possession. Consider, ma’am—agitation of the moment—brooch fell out in the street. Possible, you know, quite possible. Daresay you don’t recollect perfectly, but depend upon it that’s what happened.”

“I do recollect p-perfectly!” said Horatia. “I w-wasn’t drunk!”

Sir Roland was so much abashed at this that he relapsed into a blushful silence. It was left to the Viscount to expostulate. “Now, that’ll do Horry, that’ll do! Who said you were? Pom didn’t mean anything of the kind, did you, Pom?”

“N-no, but you were, b-both of you!” said Horatia.

“Never mind about that,” replied the Viscount hastily. “Nothing to do with the point. Pom may be right, though I don’t say he is. But if you did drop it in the street, there’s no more to be done. We can’t go all the way to Half-Moon Street hunting in the gutters.”

Horatia clasped his wrist. “P-Pel,” she said earnestly, “I d-did drop it in Lethbridge’s house. He tore my lace and it was p-pinned to it. It has a very stiff catch and c-couldn’t fall out just for n-no reason.”

“Well, if that’s so,” said the Viscount, “I’ll have to go and see Lethbridge myself. Ten to one it was all that talk about Pom’s great-aunt that made him suspicious.”

This plan did not commend itself to either of his hearers. Sir Roland was unable to believe that where tact had failed the Viscount’s crude methods were likely to succeed, and Horatia was terrified lest her hot-headed brother should attempt to recover the brooch at the sword’s point. A lively discussion was only interrupted by the entrance of the butler announcing luncheon.

Both the visitors partook of this meal with Horatia, the Viscount needing no persuasion, and Sir Roland very little. While the servants were in the room the subject of the brooch had necessarily to be abandoned, but no sooner were the covers withdrawn than Horatia took it up again just where it had been dropped, and said: “D-don’t you see, Pel, if you go to Lethbridge now that Sir Roland has already been, he m-must suspect the truth?”

“If you ask me,” replied the Viscount, “he knew all along. Great-aunt! Well, I’ve a better notion than that.”

“P-Pel, I do wish you wouldn’t!” said Horatia worriedly. “You know what you are! You fought Crosby, and there was a scandal. I know you’ll d-do the same with Lethbridge if you see him.”

“No, I shan’t,” answered the Viscount. “He’s a better swordsman than I am, but he ain’t a better shot.”

Sir Roland gaped at him. “Mustn’t make this a shooting affair, Pel. Sister’s reputation! Monstrous delicate matter.”

He broke off, for the door had opened.

“Captain Heron!” announced the footman.

There was a moment’s amazed silence. Captain Heron walked in, and pausing on the threshold, glanced smilingly round. “Well, Horry, don’t look at me as though you thought I was a ghost!” he said.

“Ghosts!” exclaimed the Viscount. “We’ve had enough of them. What brings you to town, Edward?”

Horatia had sprung up out of her chair. “Edward! Oh, have you brought L-Lizzie?”

Captain Heron shook his head. “No, I’m sorry, my dear, but Elizabeth is still in Bath. I am only in town for a few days.”

Horatia embraced him warmly. “Well, n-never mind. I am so very g-glad to see you, Edward. Oh, do you know Sir Roland P-Pommeroy?”

“I believe I have not that pleasure,” said Captain Heron, exchanging bows with Sir Roland. “Is Rule from home, Horry?”

“Yes, thank g-goodness!” she answered. “Oh, I d-don’t mean that, but I am in a d-dreadful fix, you see. Have you had luncheon?”

“I lunched in South Street. What has happened?”

“Painful affair,” said Sir Roland. “Best say nothing, ma’am.”

“Oh, Edward is perfectly safe! Why, he’s my brother-in-law. P-Pel, don’t you think perhaps Edward could help us?”

“No, I don’t,” said the Viscount bluntly. “We don’t want any help. I’ll get the brooch back for you.”

Horatia clasped Captain Heron’s arm. “Edward, p-please tell Pelham he m-mustn’t fight Lord L-Lethbridge! It would be fatal!”

“Fight Lord Lethbridge?” repeated Captain Heron. “It sounds a most unwise thing to do. Why should he?”

“We can’t explain all that now,” said the Viscount. “Who said I was going to fight him?”

“You d-did! You said he w-wasn’t a better shot than you are.”

“Well, he ain’t. All I’ve got to do is to put a pistol to the fellow’s head, and tell him to hand over the brooch.”

Horatia released Captain Heron’s arm. “I m-must say, that is a very clever plan, P-Pel!” she approved.

Captain Heron looked from one to the other, half laughing, half startled. “But you’re all very murderous!” he expostulated. “I wish you would tell me what has happened.”

“Oh, it’s nothing,” said the Viscount. “That fellow Lethbridge got Horry into his house last night, and she dropped a brooch there.”

“Yes, and he wants to c-compromise me,” nodded Horatia. “So you see, he won’t give the brooch up. It’s all d-dreadfully provoking.”

The Viscount got up. “I’ll get it back for you,” he said. “And we won’t have any damned tact about it.”

“I’ll come with you, Pel,” said the crestfallen Sir Roland.

“You can come home with me while I get the pistols,”replied the Viscount severely, “but I won’t have you going with me to Half-Moon Street, mind.”

He went out, accompanied by his friend. Horatia sighed. “I d-do hope he’ll get it this time. Come into the library, Edward, and tell me all about L-Lizzie. Why didn’t she c-come with you?”

Captain Heron opened the door for her to pass out into the hall. “It was not considered advisable,” he said, “but I am charged with messages for you.”

“N-Not advisable? Why not?” asked Horatia, looking over her shoulder.

Captain Heron waited until they had reached the library before he answered. “You see, Horry, I am happy to tell you that Lizzie is in a delicate situation just now.”

“Happy to tell me?” echoed Horatia. “Oh! Oh, I see! How famous, Edward! Why, I shall be an aunt! Rule shall take me to B-Bath directly after the Newmarket M-meeting. That is, if he d-doesn’t divorce me,” she added gloomily.

“Good God, Horry, it’s not as bad as that?” cried Heron, aghast.

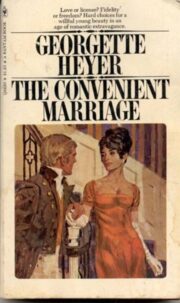

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.