This was not a very promising start, but his anger had chased from Mr Drelincourt’s mind all memory of his last meeting with the Earl, and he was undaunted. “Cousin,” he said, his words tripping over one another. “I am here on a matter of grave moment. I must beg a word with you alone!”

“I imagine it must indeed be of grave moment to induce you to come over thirty miles in pursuit of me,” said his lordship.

Mr Gisborne got up. “I will leave you, sir.” He bowed slightly to Mr Drelincourt, who paid not the slightest heed to him, and went out.

Mr Drelincourt pulled a chair out from the table and sat down. “I regret extremely, Rule, but you must prepare yourself for the most unpleasant tidings. If I did not consider it my duty to appraise you of what I have discovered, I should shrink from the task!”

The Earl did not seem to be alarmed. He still sat at his ease, one hand lying on the table, the fingers crooked round the stem of his wine-glass, his calm gaze resting on Mr Drelincourt’s face. “This self-immolation on the altar of duty is something new to me,” he remarked. “I daresay my nerves will prove strong enough to enable me to hear your tidings with—I trust—tolerable equanimity.”

“I trust so, Rule, I do indeed trust so!” said Mr Drelincourt, his eyes snapping. “You are pleased to sneer at my notion of duty—”

“I hesitate to interrupt you, Crosby, but you may have noticed that I never sneer.”

“Very well, cousin, very well! Be that as it may, you will allow that I have my share of family pride.”

“Certainly, if you tell me so,” replied the Earl gently.

Mr Drelincourt flushed. “I do tell you so! Our name—our honour, mean as much to me as to you, I believe! It is on that score that I am here now.”

“If you have come all this way to inform me that the catchpolls are after you, Crosby, it is only fair to tell you that you are wasting your time.”

“Very humorous, my lord!” cried Mr Drelincourt. “My errand, however, concerns you more nearly than that! Last night—I should rather say this morning, for it was long past two by my watch—I had occasion to visit my Lord Lethbridge.”

“That is, of course, interesting,” said the Earl. “It seems an odd hour for visiting, but I have sometimes thought, Crosby, that you are an odd creature.”

Mr Drelincourt’s bosom swelled. “There is nothing very odd, I think, in sheltering from the rain!” he said. “I was upon my way to my lodging from South Audley Street, and chanced to turn down Half-Moon Street. I was caught in a shower of rain, but observing the door of my Lord Lethbridge’s house to stand—inadvertently, I am persuaded—ajar, I stepped in. I found his lordship in a dishevelled condition in the front saloon, where a vastly elegant supper was spread, covers, my lord, being laid for two.”

“You shock me infinitely,” said the Earl, and leaning a little forward, picked up the decanter and refilled his glass.

Mr Drelincourt uttered a shrill laugh. “You may well say so! His lordship seemed put out at seeing me, remarkably put out!”

“That,” said the Earl, “I can easily understand. But pray continue, Crosby.”

“Cousin,” said Mr Drelincourt earnestly, “I desire you to believe that it is with the most profound reluctance that I do so. While I was with Lord Lethbridge, my attention was attracted to something that lay upon the floor, partly concealed by a rug. Something, Rule, that sparkled. Something—”

“Crosby,” said his lordship wearily, “your eloquence is no doubt very fine, but I must ask you to bear in mind that I have been in the saddle most of the day, and spare me any more of it. I am not really very curious to know, but you seem to be anxious to tell me: what was it that attracted your attention?”

Mr Drelincourt swallowed his annoyance. “A brooch, my lord! A lady’s corsage brooch!”

“No wonder that Lord Lethbridge was not pleased to see you,” remarked Rule.

“No wonder, indeed!” said Mr Drelincourt. “Somewhere in the house a lady was concealed at that very moment. Unseen, cousin, I picked up the brooch and slipped it into my pocket.”

The Earl raised his brows. “I think I said that you were an odd creature, Crosby.”

“It may appear so, but I had a good reason for my action. Had it not been for the fact that Lord Lethbridge pursued me on my journey here, and by force wrested the brooch from me, I should lay it before you now. For that brooch is very well known both to you and me. A ring-brooch, cousin, composed of pearls and diamonds in two circles!”

The Earl never took his eyes from Mr Drelincourt’s; it may have been a trick of the shadows thrown by the candles on the tables, but his face looked unusually grim. He swung his leg down from the arm of the chair leisurely, but still leaned back at his ease. “Yes, Crosby, a ring-brooch of pearls and diamonds?”

“Precisely, cousin! A brooch I recognized at once. A brooch that belongs to the fifteenth-century set which you gave to your—”

He got no further. In one swift movement the Earl was up, and had seized Mr Drelincourt by the throat, dragging him out of his chair, and half across the corner of the table that separated them. Mr Drelincourt’s terrified eyes goggled up into blazing grey ones. He clawed ineffectively at my lord’s hands. Speech was choked out of him. He was shaken to and fro till the teeth rattled in his head. There was a roaring in his ears, but he heard my lord’s voice quite distinctly. “You lying, mischief-making little cur!” it said. “I have been too easy with you. You dare to bring me your foul lies about my wife, and you think that I may believe them! By God, I am of a mind to kill you now!”

A moment more the crushing grip held, then my lord flung his cousin away from him, and brushed his hands together in a gesture infinitely contemptuous.

Mr Drelincourt reeled back, grasping and clutching at the air, and fell with a crash on to the floor, and stayed there, cowering away like a whipped mongrel.

The Earl looked down at him for a moment, a smile quite unlike any Mr Drelincourt had ever seen curling his fine mouth. Then he leaned back against the table, half sitting on it, supported by his hands, and said: “Get up, my friend. You are not yet dead.”

Mr Drelincourt picked himself up and tried mechanically to straighten his wig. His throat felt mangled, and his legs were shaking so that he could hardly stand. He staggered to a chair and sank into it.

“You said, I think, that Lord Lethbridge took this famous brooch from you? Where?”

Mr Drelincourt managed to say, though hoarsely: “Maidenhead.”

“I trust he will return it to its rightful owner. You realize, do you, Crosby, that your genius for recognizing my property is sometimes at fault?”

Mr Drelincourt muttered: “I thought it was—I—I may have been mistaken.”

“You were mistaken,” said his lordship.

“Yes, I—yes, I was mistaken. I beg pardon, I am sure. I am very sorry, cousin.”

“You will be still more sorry, Crosby, if one word of this passes your lips again. Do I make myself plain?”

“Yes, yes, indeed, I—I thought it my duty, no more, to—to tell you.”

“Since the day I married Horatia Winwood,” said his lordship levelly, “you have tried to make mischief between us. Failing, you were fool enough to trump up this extremely stupid story. You bring me no proof—ah, I am forgetting! Lord Lethbridge took your proof forcibly from you, did he not? That was most convenient of him.”

“But I—but he did!” said Mr Drelincourt desperately.

“I am sorry to hurt your feelings,” said the Earl, “but I do not believe you. It may console you to know that had you been able to lay that brooch before me I still should not have believed ill of my wife. I am no Othello, Crosby, I think you should have known that.” He stretched out his hand for the bell, and rang it. Upon the entrance of a footman, he said briefly: “Mr Drelincourt’s chaise.”

Mr Drelincourt heard this order with dismay. He said miserably. “But, my lord, I have not dined, and the horses are spent. I—I did not dream you would serve me so!”

“No?” said the Earl. “The Red Lion at Twyford will no doubt supply you with supper and a change of horses. Be thankful that you are leaving my house with a whole skin.”

Mr Drelincourt shrank, and said no more. In a short time the footman came back to say that the chaise was at the door. Mr Drelincourt stole a furtive glance at the Earl’s unrelenting face, and got up. “I’ll—I’ll bid you good night, Rule,” he said, trying to collect the fragments of his dignity.

The Earl nodded, and in silence watched him go out in the wake of the footman. He heard the chaise drive past the curtained windows presently, and once more rang the bell.

When the footman came back he said, absently studying his finger-nails: “I want my racing curricle, please.”

“Yes, my lord!” said the footman, startled. “Er—now, my lord?”

“At once,” replied the Earl with the greatest placidity. He got up from the table and walked unhurriedly out of the room.

Ten minutes later the curricle was at the door, and Mr Gisborne, descending the stairs, was astonished to see his lordship on the point of leaving the house, his hat on his head, and his small sword at his side. “You’re going out, sir?” he asked.

“As you see, Arnold,” replied the Earl.

“I hope, sir—nothing amiss?”

“Nothing at all, dear boy,” said his lordship.

Outside a groom was clinging to the heads of two magnificent greys, and endeavouring to control their capricious movements.

The Earl’s eye ran over them, “Fresh, eh?”

“Begging your lordship’s pardon, I’d say they were a couple of devils.”

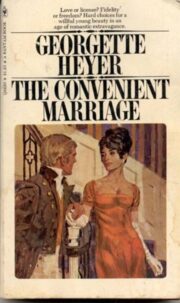

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.