“Rule!” he said bitterly. “A man fifteen years your senior! a man of his reputation. He has only to throw his glove at your feet, and you—Oh God, I cannot bear to think of it!” His writhing fingers created havoc amongst his pomaded curls. “Why must his choice light upon you?” he groaned. “Are there not others enough?”

“I think,” she said diffidently, “that he wishes to ally himself with our Family. They say he is very proud, and our name is—is also a proud one.” She hesitated, and said, colouring: “It is to be a marriage of convenience, such as are the fashion in France. Lord Rule does not—cannot—pretend to love me, nor I him.” She glanced up, as the gilt time-piece on the mantelshelf chimed the hour. “I must say goodbye to you,” she said, with desperate calm. “I promised Mama—only half an hour. Edward—” She shrank suddenly into his embrace—“Oh, my love, remember me!” she sobbed.

Three minutes later the library door slammed, and Mr Heron strode across the hall towards the front door, his hair in disorder, his gloves and cocked hat clenched in his hand.

“Edward!” The thrilling whisper came from the stairhead. He glanced up, heedless of his ravaged face and wild appearance.

The youngest Miss Winwood leaned over the balustrade, and laid a finger on her lips. “Edward, c-come up! I must speak to you!”

He hesitated, but an imperious gesture from Horatia brought him to the foot of the stairs. “What is it?” he asked curtly.

“Come up!” repeated Horatia impatiently.

He slowly mounted the stairs. His hand was seized, and he was whisked into the big withdrawing-room that overlooked the street.

Horatia shut the door. “D-don’t speak too loud! Mama’s bedroom is next door. What did she say?”

“I have not seen Lady Winwood,” Mr Heron answered heavily.

“Stupid! L-Lizzie!”

He said tightly: “Only goodbye.”

“It shan’t be!” said Horatia, with determination. “L-listen, Edward! I have a p-plan!”

He looked down at her, a gleam of hope in his eyes. “I’ll do anything!” he said. “Only tell me!”

“It isn’t anything for you to do,” said Horatia. “I am g-going to do it!”

“You?” he said doubtfully. “But what can you do?”

“I d-don’t know, but I’m g-going to try. M-mind, I can’t be sure that it will succeed, but I think perhaps it m-might.”

“But what is it?” he persisted.

“I shan’t say. I only told you because you looked so very m-miserable. You had better trust me, Edward.”

“I do,” he assured her. “But—”

Horatia pulled him to stand in front of the mirror over the fireplace. “Then straighten your hair,” she said severely. “J-just look at it. You’ve crushed your hat too. There! Now, g-go away, Edward, before Mama hears you.”

Mr Heron found himself pushed to the door. He turned and grasped Horatia’s hand. “Horry, I don’t see what you can do, but if you can save Elizabeth from this match—”

Two dimples leapt into being; the grey eyes twinkled. “I know. You w-will be my m-most obliged servant. Well, I will!”

“More than that!” he said earnestly.

“Hush, Mama will hear!” whispered Horatia, and thrust him out of the room.

Chapter Two

Mr Arnold Gisborne, lately of Queen’s College, Cambridge, was thought by his relatives to have been very fortunate to have acquired the post of secretary to the Earl of Rule. He was tolerably satisfied himself; employment in a noble house was a fair stepping-stone to a Public Career, but he would have preferred, since he was a serious young man, the service of one more nearly concerned with the Affairs of the Nation. My Lord of Rule, when he could be moved thereto, occasionally took his seat in the Upper House, and had been known to raise his pleasant, lazy voice in support of a motion, but he had no place in the Ministry, and he displayed not the smallest desire to occupy himself with Politicks. If he spoke, Mr Gisborne was requested to prepare his speech, which Mr Gisborne did with energy and enthusiasm, hearing in his imagination the words delivered in his own crisp voice. My lord would glance over the sheets of fine handwriting, and say: “Admirable, my dear Arnold, quite admirable. But not quite in my mode, do you think?” And Mr Gisborne would have sadly to watch my lord’s well-kept hand driving a quill through his most cherished periods. My lord, aware of his chagrin, would look up and say with his rather charming smile: “I feel for you, Arnold, believe me. But I am such a very frippery fellow, you know. It would shock the Lords to hear me utter such energetic sentiments. It would not do at all.”

“My lord, may I say that you like to be thought a frippery fellow?” asked Mr Gisborne with severity tempered by respect.

“By all means, Arnold. You may say just what you like,” replied his lordship amiably.

But in spite of this permission Mr Gisborne did not say anything more. It would have been a waste of time. My lord could give one a set-down, though always with that faint look of amusement in his bored grey eyes, and always in the pleasantest manner. Mr Gisborne contented himself with dreaming of his own future, and in the meantime managed his patron’s affairs with conscientious thoroughness. The Earl’s mode of life he could not approve, for he was the son of a Dean, and strictly reared. My lord’s preoccupation with such wanton pieces of pretty femininity as LaFanciola, of the Opera House, or a certain Lady Massey filled him with a disapproval that made him at first scornful, and later, when he had been my lord’s secretary for a twelve-month, regretful.

He had not imagined, upon his first setting eyes on the Earl, that he could learn to like, or even to tolerate, this lazy, faintly mocking exquisite, but he had not, after all, experienced the least difficulty in doing both. At the end of a month he had discovered that just as his lordship’s laced and scented coats concealed an extremely powerful frame, so his weary eyelids drooped over eyes that could become as keen as the brain behind. Yielding to my lord’s charm, he accepted his vagaries if not with approval at least with tolerance.

The Earl’s intention to enter the married state took him by surprise. He had no notion of such a scheme until a morning two days after his lordship had visited Lady Winwood in South Street. Then, as he sat at his desk in the library, Rule strolled in after a late breakfast, and perceiving the pen in his hand, complained: “You are always so damnably busy, Arnold. Do I give you so much work?”

Mr Gisborne got up from his seat at the desk. “No, sir, not enough.”

“You are insatiable, my dear boy.” He observed some papers in Mr Gisborne’s grasp, and sighed. “What is it now?” he asked with resignation.

“I thought, sir, you might wish to see these accounts from Meering,” suggested Mr Gisborne.

“Not in the least,” replied his lordship, leaning his big shoulders against the mantelpiece.

“Very well, sir.” Mr Gisborne laid the papers down, and said tentatively: “You won’t have forgotten that there is a Debate in the House today which you will like to take part in?”

His Lordship’s attention had wandered; he was scrutinizing his own top-boot (for he was dressed for riding) through a long-handled quizzing-glass, but he said in a mildly surprised voice: “Which I shall what, Arnold?”

“I made sure you would attend it, my lord,” said Mr Gisborne defensively.

“I am afraid you were in your cups, my dear fellow. Now tell me do my eyes deceive me, or is there a suggestion—the merest hint—of a—really, I fear I must call it a bagginess—about the ankle?”...

Mr Gisborne glanced perfunctorily down at his lordship’s shining boot.”I don’t observe it, sir.”

“Come, come, Arnold!” the Earl said gently. “Give me your attention. I beg of you!”

Mr Gisborne met the quizzical gleam in my lord’s eyes, and grinned in spite of himself. “Sir, I believe you should go. It is of some moment. In the Lower House—”

“I felt uneasy at the time,” mused the Earl, still contemplating his legs. “I shall have to change my bootmaker again.” He let his glass fall on the end of its long riband, and turned to arrange his cravat in the mirror. “Ah! Remind me, Arnold, that I am to wait on Lady Winwood at three. It is really quite important.”

Mr Gisborne stared.”Yes, sir?

“Yes, quite important. I think the new habit, the coat dos de puce—or is that a thought sombre for the errand? I believe the blue velvet will be more fitting. And the perruque a bourse? You prefer the Catogan wig, perhaps, but you are wrong, my dear boy, I am convinced you are wrong. The arrangement of curls in the front gives an impression of heaviness. I feel sure you would not wish me to be heavy.” He gave one of the lace ruffles that fell over his hand a flick. “Oh, I have not told you, have I? You must know that I am contemplating matrimony, Arnold.”

Mr Gisborne’s astonishment was plain to be seen. “You, sir?” he said, quite dumbfounded.

“But why not?” inquired his lordship. “Do you object?”

“Object, sir! I? I am only surprised.”

“My sister,” explained his lordship, “considers that it is time I took a wife.”

Mr Gisborne had a great respect for the Earl’s sister, but he had yet to learn that her advice carried any weight with his lordship. “Indeed, sir,” he said, and added diffidently: “It is Miss Winwood?”

“Miss Winwood,” agreed the Earl. “You perceive how important it is that I should not forget to present myself in South Street at—did I say three o’clock?”

“I will put you in mind of it, sir,” said Mr Gisborne dryly.

The door opened to admit a footman in blue livery. “My lord, a lady has called,” he said hesitatingly.

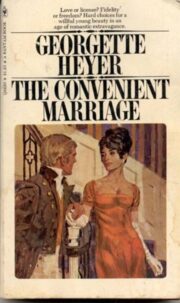

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.