Horatia said nothing, but her eyes followed Lethbridge with a speculative gleam in them.

It did not need Lady Massey’s words to spur up her interest. Lethbridge, with his hawk-eyes and his air of practised ease, had at the outset attracted her, already a trifle bored by the adulation of younger sparks. He was very much the man-of-the-world, and to add to his fascination he was held to be dangerous. At the first meeting it had seemed as though he admired her; had he shown admiration more plainly at the second his charm might have dwindled. He did not. He let half the evening pass before he approached her and then he exchanged but the barest civilities and passed on. They met at the card table at Mrs Delaney’s house. He held the bank at pharaoh and she won against the bank. He complimented her, but still with that note of mockery as though he refused to take her seriously. Yet, when she walked in the Park with Mrs Maulfrey two days later and he rode past, he reined in and sprang lightly down from the saddle and came towards her, leading his mount, and walked beside her a considerable distance, as though he were delighted to have come upon her.

“La, child!” cried Mrs Maulfrey, when at last he took his leave of them. “You’d best have a care—he’s a wicked rake, my dear! Don’t fall in love with him, I beg of you!”

“F-fall in love!” said Horatia scornfully. “I want to play c-cards with him!”

He was at the Duchess of Queensberry’s ball, and did not once approach her. She was piqued, and never thought to blame Rule’s presence for his defection. Yet when she visited the Pantheon in Lady Amelia Pridham’s party, Lethbridge, arriving solitary midway through the evening, singled her out and was so assiduous in his attentions that he led her to suppose that at last they were becoming intimate. But upon a young gentleman’s approaching to claim Horatia’s attention his lordship relinquished her with a perfectly good grace and very soon afterwards withdrew to the card-room. It was really most provoking, quite enough to make any lady determined to plan his downfall, and it did much to spoil her enjoyment of the party. Indeed, the evening was not a success. The Pantheon, so bright and new, was very fine, of course, with its pillars and its stucco ceilings and its great glazed dome, but Lady Amelia, most perversely, did not want to play cards, and in one of the country dances Mr Laxby, awkward creature, trod on the edge of her gown of diaphanous Jouy cambric just come from Paris, and tore the hem past repair. Then, too, she was obliged to decline going for a picnic out to Ewell on the following day on the score of having promised to drive to Kensington (of all stuffy places!) to visit her old governess, who was living there with a widowed sister. She had half a notion that Lethbridge was to be at the picnic and was seriously tempted to bury Miss Lane in oblivion. However, the thought of poor Laney’s disappointment prevented her from taking this extreme step, and she resolutely withstood all the entreaties of her friends.

The afternoon dutifully spent in Kensington proved to be just as dull as she had feared it would be and Laney, so anxious to know all she had been doing, so full of tiresome gossip, made it impossible for her to leave as soon as she would have liked to have done. It was very nearly half past four before she entered her coach, but fortunately she was to dine at home that evening before going with Rule to the Opera, so that it did not greatly signify that she was bound to be late. But she felt that she had spent an odious day, the only ray of consolation—and that, she admitted, a horridly selfish one—being that the weather, which had promised so well in the morning, had become extremely inclement, quite unsuitable for picnics, the sky being overcast by lunch-time, and some thunderous clouds gathering which made the light very bad as early as four o’clock. A threatening rumble sounded as she stepped into the coach, and Miss Lane at once desired her to remain on until the storm had passed. Luckily the coachman was confident that it would hold off for some time yet, so that Horatia was not obliged to accept this invitation. The coachman was somewhat startled at receiving a command from her ladyship to spring his horses, as she was monstrously late. He touched his hat in a reluctant assent and wondered what the Earl would say if it came to his ears that his wife was driven into town at the gallop.

It was, accordingly, at a spanking pace that the coach headed eastwards, but a flash of lightning making one of the leaders shy badly across the road, the coachman soon steadied the pace, which, indeed, he had some trouble in maintaining, both his wheelers being good holders and quite unused to so headlong a method of progression.

The rain still held off, but lightning quivered frequently and the noise of thunder afar became practically continuous, while the heavy clouds overhead obscured the daylight very considerably and made the coachman anxious to pass the Knightsbridge toll-gate as soon as possible.

A short distance beyond the Halfway House, an inn midway between Knightsbridge and Kensington, a group of some three or four horsemen, imperfectly concealed by a clump of trees just off the road, most unpleasantly assailed the vision of both the men on the box. They were some way ahead, and it was difficult in the uncertain light to observe them very particularly. Some heavy drops of rain had begun to fall, and it was conceivable that the horsemen were merely seeking shelter from the imminent downpour. But the locality had a bad reputation, and although the hour was too early for highwaymen to be abroad the coachman whipped up his horses with the intention of passing the dangerous point at the gallop, and recommended the groom beside him to be ready with the blunderbuss.

That worthy, peering uneasily ahead, disclosed the fact that he had not thought proper to bring this weapon, the expedition hardly being of a nature to render such a precaution necessary. The coachman, keeping to the crown of the road, tried to assure himself that no highwaymen would dare to venture forth in broad daylight. “Sheltering from the rain, that’s all,” he grunted, adding rather inconsequently: “Saw a couple of men hanged at Tyburn once. Robbing the Portsmouth Mail. Desperate rogues, they was.”

They were now come within hailing distance of the mysterious riders, and to both men’s dismay the group disintegrated and the three horsemen spread themselves across the road in a manner leaving no room for doubt of their intentions.

The coachman cursed under his breath, but being a stouthearted fellow lashed his horses to a still wilder pace in the hope of charging through the chain across the road. A shot, whistling alarmingly by his head, made him flinch involuntarily, and at the same moment the groom, quite pale with fright, grabbed at the reins and hauled on them with all his strength. A second shot set the horses swerving and plunging, and while the coachman and groom fought for possession of the reins a couple of the frieze-clad ruffians rode up and seized the leaders’ bridles, and so brought the whole equipage to a standstill.

The third man, a big fellow with a mask covering his entire face, pressed up to the coach, shouting: “Stand and deliver!” and leaning from the saddle wrenched open the door.

Horatia, startled, but as yet unalarmed, found herself confronted by a large horse-pistol, held in a grimy hand. Her astonished gaze travelled upwards to the curtain-mask and she cried out: “Gracious! F-foot-pads!”

A laugh greeted this exclamation and the man holding the barker said in a beery voice: “Bridle culls, my pretty! We bain’t no foot-scamperers! Hand over the gewgaws and hand ’em quick, see?”

“I shan’t!” said Horatia, grasping her reticule firmly.

It seemed as though the highwayman was rather at a loss, but while he hesitated a second masked rider jostled him out of the way and made a snatch at the reticule. “Ho-ho, there’s a fat truss!” he gloated, wresting it from her, “and a rum fam on your finger too! Now softly, softly!”

Horatia, far more angry than she was frightened at having her purse wrenched from her, tried to pull her hand away, and failing, dealt her assailant a ringing slap.

“How dare you, you odious p-person!” she raged.

This was productive only of another coarse guffaw, and she was beginning to feel really rather alarmed when a voice suddenly shouted: “Lope off! Lope off! or we’ll be snabbled! Coves on the road!”

Almost at the same moment a shot sounded, and hooves could be heard thundering down the road. The highwayman released Horatia in a twinkling; another shot exploded; there was a great deal of shouting and stamping and the highwaymen galloped off into the dusk. The next instant a rider on a fine bay dashed up to the coach and reined in his horse, rearing and plunging. “Madam!” the newcomer said sharply, and then in tones of the utmost surprise: “My Lady Rule! Good God, ma’am, are you hurt?”

“W-why, it’s you!” cried Horatia. “No, I’m n-not in the least hurt.”

Lord Lethbridge swung himself out of the saddle and stepped lightly up on to the step of the coach, taking Horatia’s hand in his. “Thank God I chanced to be at hand!” he said. “There is nothing to frighten you now, ma’am. The rogues are fled.”

Horatia, an unsatisfactory heroine, replied gaily: “Oh, I w-wasn’t frightened, sir! It is the m-most exciting thing that has ever happened to m-me! But I must say I think they were very cowardly robbers to run away from one m-man.”

A soundless laugh shook his lordship. “Perhaps they ran away from my pistols,” he suggested. “So long as they have not harmed you—”

“Oh, n-no! But how came you on this road my l-lord?”

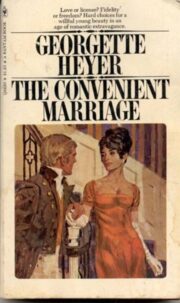

"The Convenient Marriage" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Convenient Marriage". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Convenient Marriage" друзьям в соцсетях.