WINTER 1512

It came as no surprise to Katherine, nor to the cynics on the council when the English army came home in dishonored tatters in December. Lord Dorset, despairing of ever receiving orders and reinforcements from King Ferdinand, confronted by mutinying troops—hungry, weary, and with two thousand men lost to illness—straggled home in disgrace, as he had taken them out in glory.

“What can have gone wrong?” Henry rushed into Katherine’s rooms and waved away her ladies-in-waiting. He was almost in tears of rage at the shame of the defeat. He could not believe that his force that had gone out so bravely should come home in such disarray. He had letters from his father-in-law complaining of the behavior of the English allies. He had lost face in Spain, he had lost face with his enemy France. He fled to Katherine as the only person in the world who would share his shock and dismay. He was almost stammering with distress, it was the first time in his reign that anything had gone wrong and he had thought—like a boy—that nothing would ever go wrong for him.

I take his hands. I have been waiting for this since the first moment in the summer when there was no battle plan for the English troops. As soon as they arrived and were not deployed I knew that we had been misled. Worse, I knew that we had been misled by my father.

I am no fool. I know my father as a commander, and I know him as a man. When he did not fling the English into battle on the day that they arrived, I knew that he had another plan for them, and that plan was hidden from us. My father would never leave good men in camp to gossip and drink and get sick. I was on campaign with my father for most of my childhood. I never saw him let the men sit idle. He always keeps his men moving, he always keeps them in work and out of mischief. There is not a horse in my father’s stables with a pound of extra fat on it; he treats his soldiers just the same.

If the English were left to rot in camp, it was because he had need of them just where they were—in camp. He did not care that they were getting sick and lazy. That made me look again at the map and I saw what he was doing. He was using them as a counterweight, as an inactive diversion. I read the reports from our commanders as they arrived—their complaints at their pointless inaction, their exercises on the border, sighting the French army and being seen by them, but not being ordered to engage—and I knew I was right. My father kept the English troops dancing on the spot in Fuenterrabia so that the French, alarmed by such a force on their flank, would place their army in defense. Guarding against the English they could not attack my father who, joyously alone and unencumbered, at the head of his troops, marched into the unprotected kingdom of Navarre and so picked up that which he had desired for so long at no expense or danger to himself.

“My dear, your soldiers were not tried and found wanting,” I say to my distressed young husband. “There is no question as to the courage of the English. There can be no doubting you.”

“He says…” He waves the letter at me.

“It doesn’t matter what he says,” I say patiently. “You have to look at what he does.”

The face he turns to me is so hurt that I cannot bring myself to tell him that my father has used him, played him for a fool, used his army, used even me, to win himself Navarre.

“My father has taken his fee before his work, that is all,” I say robustly. “Now we have to make him do the work.”

“What do you mean?” Henry is still puzzled.

“God forgive me for saying it, but my father is a masterly double-dealer. If we are going to make treaties with him, we will have to learn to be as clever as him. He made a treaty with us and said he would be our partner in war against France, but all we have done is win him Navarre, by sending our army out and home again.”

“They have been shamed. I have been shamed.”

He cannot understand what I am trying to tell him. “Your army has done exactly what my father wanted them to do. In that sense, it has been a most successful campaign.”

“They did nothing! He complains to me that they are good for nothing!”

“They pinned down the French with that nothing. Think of that! The French have lost Navarre.”

“I want to court-martial Dorset!”

“Yes, we can do so, if you wish. But the main thing is that we still have our army, we have lost only two thousand men, and my father is our ally. He owes us for this year. Next year you can go back to France and this time Father will fight for us, not us for him.”

“He says he will conquer Guienne for me; he says it as if I cannot do it myself! He speaks to me as a weakling with a useless force!”

“Good,” I say, surprising him. “Let him conquer Guienne for us.”

“He wants us to pay him.”

“Let us pay for it. What does it matter as long as my father is on our side when we go to war with the French? If he wins Guienne for us, then that is to our good; if he does not, but just distracts the French when we invade in the north from Calais, then that is all to the good as well.”

For a moment he gapes at me, his head spinning. Then he sees what I mean. “He pins down the French for us as we advance, just as we did for him?”

“Exactly.”

“We use him, as he used us?”

“Yes.”

He is amazed. “Did your father teach you how to do this—to plan ahead as if a campaign were a chessboard, and you have to move the pieces around?”

I shake my head. “Not on purpose. But you cannot live with a man like my father without learning the arts of diplomacy. You know Machiavelli himself called him the perfect prince? You could not be at my father’s court, as I was, or on campaign with him, as I was, without seeing that he spends his life seeking advantage. He taught me every day. I could not help but learn, just from watching him. I know how his mind works. I know how a general thinks.”

“But what made you think of invading from Calais?”

“Oh, my dear, where else would England invade France? My father can fight in the south for us, and we will see if he can win us Guienne. You can be sure that he will do so if it is in his interest. And, at any rate, while he is doing that, the French will not be able to defend Normandy.”

Henry’s confidence comes rushing back to him. “I shall go myself,” he declares. “I shall take to the field of battle myself. Your father will not be able to criticize the command of the English army if I do it myself.”

For a moment I hesitate. Even playing at war is a dangerous game, and while we do not have an heir, Henry is precious beyond belief. Without him, the safety of England will be torn between a hundred pretenders. But I will never keep my hold on him if I coop him up as his grandmother did. Henry will have to learn the nature of war, and I know that he will be safest in a campaign commanded by my father, who wants to keep me on my throne as much as I want it; and safer by far facing the chivalrous French than the murderous Scots. Besides, I have a plan that is a secret. And it requires him to be out of the country.

“Yes, you shall,” I say. “And you shall have the best armor and strongest horse and handsomest guard of any other king who takes the field.”

“Thomas Howard says that we should abandon our battle against France until we have suppressed the Scots.”

I shake my head. “You shall fight in France in the alliance of the three kings,” I assure him. “It will be a mighty war, one that everyone will remember. The Scots are a minor danger, they can wait. At the worst they are a petty border raid. And if they invade the north when you go to war, they are so unimportant that even I could command an expedition against them while you go to the real war in France.”

“You?” he asks.

“Why not? Are we not a king and queen come young to our thrones in our power? Who should deny us?”

“No one! I shall not be diverted,” Henry declares. “I shall conquer in France and you shall guard us against the Scots.”

“I will,” I promise him. This is just what I want.

SPRING 1513

Henry talked of nothing but war all winter, and in the spring Katherine started a great muster of men and materials for the invasion of northern France. The treaty with Ferdinand agreed that he would invade Guienne for England at the same time as the English troops took Normandy. The Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian would join with the English army in the battle in the north. It was an infallible plan if the three parties attacked simultaneously, if they kept meticulous faith with each other.

It comes as no surprise to me to find that my father has been talking peace with France in the very same days that I have had Thomas Wolsey, my right-hand man, the royal almoner, writing to every town in England and asking them how many men they can muster for the king’s service when we go to war in France. I knew my father would think only of the survival of Spain: Spain before everything. I do not blame him for it. Now that I am a queen I understand a little better what it means to love a country with such a passion that one will betray anything—even one’s own child, as he does—to keep it safe. My father, with the prospect on one hand of a troublesome war and little gain and, on the other hand peace, with everything to play for, chooses peace and chooses France as his friend. He has betrayed us in absolute secrecy and he fooled even me.

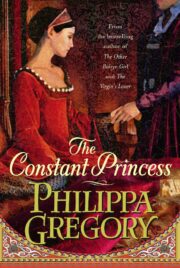

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.