“I don’t know what he is talking about,” Henry complained to Katherine, finding her in the garden playing at catch with her ladies-in-waiting. He was too disturbed to run into the game as he usually did and snatch the ball from the air, bowl it hard at the nearest girl, and shout with joy. He was too worried even to play with them. “What is he saying? I have never appealed to the Pope. I did not report him. I am no talebearer!”

“No, you are not, and so you can tell him,” Katherine said serenely, slipping her hand in his arm and walking away from the women.

“I shall tell him. I said nothing to the Pope, and I can prove it.”

“I may have mentioned my concerns to the archbishop and he may have passed them on,” Katherine said casually. “But you can hardly be blamed if your wife tells her spiritual advisor that she is anxious.”

“Exactly,” Henry said. “I shall tell him so. And you should not be worried for a moment.”

“Yes. And the main thing is that James knows he cannot attack us with impunity, His Holiness has made a ruling.”

Henry hesitated. “You did not mean Bainbridge to tell the Pope, did you?”

She peeped a little smile at him. “Of course,” she said. “But it still is not you who has complained of James to the Pope.”

His grip tightened around her waist. “You are a redoubtable enemy. I hope we are never on opposing sides. I should be sure to lose.”

“We never will be,” she said sweetly. “For I will never be anything but your loyal and faithful wife and queen.”

“I can raise an army in a moment, you know,” Henry reminded her. “There is no need for you to fear James. There is no need for you even to pretend to fear. I could be the hammer of the Scots. I could do it as well as anyone, you know.”

“Yes, of course you can. And, thank God, now you don’t need to do so.”

AUTUMN 1511

Edward Howard brought the Scots privateers back to London in chains and was greeted as an English hero. His popularity made Henry—always alert to the acclaim of the people—quite envious. He spoke more and more often of a war against the Scots, and the Privy Council, though fearful of the cost of war and privately doubtful of Henry’s military abilities, could not deny that Scotland was an ever-present threat to the peace and security of England.

It was the queen who diverted Henry from his envy of Edward Howard and the queen who continually reminded him that his first taste of warfare should surely be in the grand fields of Europe and not in some half-hidden hills in the borders. When Henry of England rode out it should be against the French king, in alliance with the two other greatest kings of Christendom. Henry, inspired from childhood with tales of Crécy and Agincourt, was easy to seduce with thoughts of glory against France.

SPRING 1512

It was hard for Henry not to embark in person when the fleet sailed to join King Ferdinand’s campaign against the French. It was a glorious start: the ships went out flying the banners of most of the great houses of England, they were the best-equipped, finest-arrayed force that had left England in years. Katherine had been busy, supervising the endless work of provisioning the ships, stocking the armories, equipping the soldiers. She remembered her mother’s constant work when her father was at war, and she had learned the great lesson of her childhood—that a battle could only be won if it were thoroughly and reliably supplied.

She sent out an expeditionary fleet that was better organized than any that had gone from England before, and she was confident that under her father’s command they would defend the Pope, beat the French, win lands in France, and establish the English as major landowners in France once more. The peace party on the Privy Council worried, as they always did, that England would be dragged into another endless war, but Henry and Katherine were convinced by Ferdinand’s confident predictions that a victory would come quickly and there would be rich gains for England.

I have seen my father command one campaign after another for all of my childhood. I have never seen him lose. Going to war is to relive my childhood again, the colors and the sounds and the excitement of a country at war are a deep joy for me. This time, to be in alliance with my father, as an equal partner, to be able to deliver to him the power of the English army, feels like my coming-of-age. This is what he has wanted from me, this is the fulfillment of my life as his daughter. It is for this that I endured the long years of waiting for the English throne. This is my destiny, at last. I am a commander as my father is, as my mother was. I am a Queen Militant, and there is no doubt in my mind on this sunny morning as I watch the fleet set sail that I will be a Queen Triumphant.

The plan was that the English army would meet the Spanish army and invade southwestern France: Guienne and the Duchy of Aquitaine. There was no doubt in Katherine’s mind that her father would take his share of the spoils of war, but she expected that he would honor his promise to march with the English into Aquitaine and win it back for England. She thought that his secret plan would be the carving up of France, which would return that overmighty country to the collection of small kingdoms and duchies it once had been, their ambitions crushed for a generation. Indeed, Katherine knew her father believed that it was safer for Christendom if France were reduced. It was not a country that could be trusted with the power and wealth that unity brings.

MAY 1512

It was as good as any brilliant court entertainment to see the ships cross the bar and sail out, a strong wind behind them, on a sunny day; and Henry and Katherine rode back to Windsor filled with confidence that their armies would be the strongest in Christendom, that they could not fail.

Katherine took advantage of the moment and Henry’s enthusiasm for the ships to ask him if he did not think that they should build galleys, fighting ships powered with oars. Arthur had known at once what she had meant by galleys; he had seen drawings and had read how they could be deployed. Henry had never seen a battle at sea, nor had he seen a galley turn without wind in a moment and come against a becalmed fighting ship. Katherine tried to explain to him, but Henry, inspired by the sight of the fleet in full sail, swore that he wanted only sailing ships, great ships manned with free crews, named for glory.

The whole court agreed with him, and Katherine knew she could make no headway against a court that was always blown about by the latest fashion. Since the fleet had looked so very fine when it set sail, all the young men wanted to be admirals like Edward Howard, just as the summer before they had all wanted to be crusaders. There was no discussing the weakness of big sailing ships in close combat—they all wanted to set out with full sail. They all wanted their own ship. Henry spent days with shipwrights and shipbuilders, and Edward Howard argued for a greater and greater navy.

Katherine agreed that the fleet was very fine, and the sailors of England were the finest in the world, but remarked that she thought she might write to the arsenal at Venice to ask them the cost of a galley and if they would build it as a commission or if they would agree to send the parts and plans to England, for English shipwrights to assemble in English dockyards.

“We don’t need galleys,” Henry said dismissively. “Galleys are for raids on shore. We are not pirates. We want great ships that can carry our soldiers. We want great ships that can tackle the French ships at sea. The ship is a platform from which you launch your attack. The greater the platform, the more soldiers can muster. It has to be a big ship for a battle at sea.”

“I am sure you are right,” she said. “But we must not forget our other enemies. The seas are one border, and we must dominate them with ships both great and small. But our other border must be made safe too.”

“D’you mean the Scots? They have taken their warning from the Pope. I don’t expect to be troubled with them.”

She smiled. She would never openly disagree with him. “Certainly,” she said. “The archbishop has secured us a breathing space. But next year, or the year after, we will have to go against the Scots.”

SUMMER 1512

Then there was nothing for Katherine to do but to wait. It seemed as if everyone was waiting. The English army were in Fuenterrabia, waiting for the Spanish to join with them for their invasion of southern France. The heat of the summer came on as they kicked their heels, ate badly, and drank like thirsty madmen. Katherine alone of Henry’s council knew that the heat of midsummer Spain could kill an army as they did nothing but wait for orders. She concealed her fears from Henry and from the council, but privately she wrote to her father asking what his plans were, she tackled his ambassador asking him what her father intended the English army to do, and when should they march?

Her father, riding with his own army, on the move, did not reply; and the ambassador did not know.

The summer wore on. Katherine did not write again. In a bitter moment, which she did not even acknowledge to herself, she saw that she was not her father’s ally on the chessboard of Europe—she realized that she was nothing more than a pawn in his plan. She did not need to ask her father’s strategy; once he had the English army in place and did not use them, she guessed it.

It grew colder in England, but it was still hot in Spain. At last Ferdinand had a use for his allies, but when he sent for them, and ordered that they should spend the winter season on campaign, they refused to answer his call. They mutinied against their own commanders and demanded to go home.

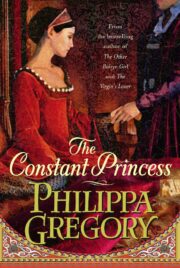

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.