“I shall speak to the Spanish ambassador today.”

She thought she had never seen such a bright gladness in his face. “I suppose I can teach her.” She gestured to the books before her. “She will have much to learn.”

“I shall tell the ambassador to propose it to Their Majesties of Spain and I shall talk to her tomorrow.”

“You will go again so soon?” she asked curiously.

Henry nodded. He would not tell her that even to wait till tomorrow seemed too long. If he had been free to do so, he would have gone back straightaway and asked her to marry him that very night, as if he were a humble squire and she a maid, and not King of England and Princess of Spain; father- and daughter-in-law.

Henry saw that Dr. de Puebla the Spanish ambassador was invited to Whitehall in time for dinner, given a seat at one of the top tables, and plied with the best wine. Some venison, hanged to perfection and cooked in a brandywine sauce, came to the king’s table; he helped himself to a small portion and sent the dish to the Spanish ambassador. De Puebla, who had not experienced such favors since first negotiating the Infanta’s marriage contract, loaded his plate with a heavy spoon and dipped the best manchet bread into the gravy, glad to eat well at court, wondering quietly behind his avid smile what it might mean.

The king’s mother nodded towards him, and de Puebla rose up from his seat to bow to her. “Most gracious,” he remarked to himself as he sat down once more. “Extremely. Exceptionally.”

He was no fool, he knew that something would be required for all these public favors. But given the horror of the past year—when the hopes of Spain had been buried beneath the nave in Worcester Cathedral—at least these were straws in a good wind. Clearly, King Henry had a use for him again as something other than a whipping boy for the failure of the Spanish sovereigns to pay their debts.

De Puebla had tried to defend Their Majesties of Spain to an increasingly irritable English king. He had tried to explain to them in long, detailed letters that it was fruitless asking for Catalina’s widow’s jointure if they would not pay the remainder of the dowry. He tried to explain to Catalina that he could not make the English king pay a more generous allowance for the upkeep of her household, nor could he persuade the Spanish king to give his daughter financial support. Both kings were utterly stubborn, both quite determined to force the other into a weak position. Neither seemed to care that in the meantime Catalina, only seventeen, was forced to keep house with an extravagant entourage in a foreign land on next to no money. Neither king would take the first step and undertake to be responsible for her keep, fearing that this would commit him to keeping her and her household forever.

De Puebla smiled up at the king, seated on his throne under the canopy of state. He genuinely liked King Henry, he admired the courage with which he had seized and held the throne, he liked the man’s direct good sense. And more than that, de Puebla liked living in England; he was accustomed to his good house in London, to the importance conferred on him by representing the newest and most powerful ruling house in Europe. He liked the fact that his Jewish background and recent conversion were utterly ignored in England, since everyone at this court had come from nowhere and changed their name or their affiliation at least once. England suited de Puebla, and he would do his best to remain. If it meant serving the King of England better than the King of Spain, he thought it was a small compromise to make.

Henry rose from the throne and gave the signal that the servers could clear the plates. They swept the board and cleared the trestle tables, and Henry strolled among the diners, pausing for a word here and there, still very much the commander among his men. All the favorites at the Tudor court were the gamblers who had put their swords behind their words and marched into England with Henry. They knew their value to him, and he knew his to them. It was still a victors’ camp rather than a softened civilian court.

At length Henry completed his circuit and came to de Puebla’s table. “Ambassador,” he greeted him.

De Puebla bowed low. “I thank you for your gift of the dish of venison,” he said. “It was delicious.”

The king nodded. “I would have a word with you.”

“Of course.”

“Privately.”

The two men strolled to a quieter corner of the hall while the musicians in the gallery struck a note and began to play.

“I have a proposal to resolve the issue of the Dowager Princess,” Henry said as drily as possible.

“Indeed?”

“You may find my suggestion unusual, but I think it has much to recommend it.”

“At last,” de Puebla thought. “He is going to propose Harry. I thought he was going to let her sink a lot lower before he did that. I thought he would bring her down so that he could charge us double for a second try at Wales. But, so be it. God is merciful.”

“Ah, yes?” de Puebla said aloud.

“I suggest that we forget the issue of the dowry,” Henry started. “Her goods will be absorbed into my household. I shall pay her an appropriate allowance, as I did for the late Queen Elizabeth—God bless her. I shall marry the Infanta myself.”

De Puebla was almost too shocked to speak. “You?”

“I. Is there any reason why not?”

The ambassador gulped, drew a breath, managed to say, “No, no, at least…I suppose there could be an objection on the grounds of affinity.”

“I shall apply for a dispensation. I take it that you are certain that the marriage was not consummated?”

“Certain,” de Puebla gasped.

“You assured me of that on her word?”

“The duenna said…”

“Then it is nothing,” the king ruled. “They were little more than promised to one another. Hardly man and wife.”

“I will have to put this to Their Majesties of Spain,” de Puebla said, desperately trying to assemble some order to his whirling thoughts, striving to keep his deep shock from his face. “Does the Privy Council agree?” he asked, playing for time. “The Archbishop of Canterbury?”

“It is a matter between ourselves at the moment,” Henry said grandly. “It is early days for me as a widower. I want to be able to reassure Their Majesties that their daughter will be cared for. It has been a difficult year for her.”

“If she could have gone home…”

“Now there will be no need for her to go home. Her home is England. This is her country,” Henry said flatly. “She shall be queen here, as she was brought up to be.”

De Puebla could hardly speak for shock at the suggestion that this old man, who had just buried his wife, should marry his dead son’s bride. “Of course. So, shall I tell Their Majesties that you are quite determined on this course? There is no other arrangement that we should consider?” De Puebla racked his brains as to how he could bring in the name of Prince Harry, who was surely Catalina’s most appropriate future husband. Finally, he plunged in. “Your son, for instance?”

“My son is too young to be considered for marriage as yet.” Henry disposed of the suggestion with speed. “He is eleven and a strong, forward boy, but his grandmother insists that we plan nothing for him for another four years. And by then, the Princess Dowager would be twenty-one.”

“Still young,” gasped de Puebla. “Still a young woman, and near him in age.”

“I don’t think Their Majesties would want their daughter to stay in England for another four years without husband or household of her own,” Henry said with unconcealed threat. “They could hardly want her to wait for Harry’s majority. What would she do in those years? Where would she live? Are they proposing to buy her a palace and set up a household for her? Are they prepared to give her an income? A court, appropriate to her position? For four years?”

“If she could return to Spain to wait?” de Puebla hazarded.

“She can leave at once, if she will pay the full amount of her dowry and find her own fortune elsewhere. Do you really think she can get a better offer than Queen of England? Take her away if you do!”

It was the sticking point that they had reached over and over again in the past year. De Puebla knew he was beaten. “I will write to Their Majesties tonight,” he said.

I dreamed I was a swift, flying over the golden hills of the Sierra Nevada. But this time, I was flying north, the hot afternoon sun was on my left, ahead of me was a gathering of cool cloud. Then suddenly, the cloud took shape. It was Ludlow Castle, and my little bird heart fluttered at the sight of it and at the thought of the night that would come when he would take me in his arms and press down on me, and I would melt with desire for him.

Then I saw it was not Ludlow but these great gray walls were those of Windsor Castle, and the curve of the river was the great gray glass of the river Thames, and all the traffic plying up and down and the great ships at anchor were the wealth and the bustle of the English. I knew I was far from my home, and yet I was at home. This would be my home. I would build a little nest against the gray stone of the towers here, just as I would have done in Spain. And here they would call me a swift; a bird which flies so fast that no one has ever seen it land, a bird that flies so high that they think it never touches the ground. I shall not be Catalina, the Infanta of Spain. I shall be Katherine of Aragon, Queen of England, just as Arthur named me: Katherine, Queen of England.

“The king is here again,” Doña Elvira said, looking out of the window. “He has ridden here with just two men. Not even a standard-bearer or guards.” She sniffed. The widespread English informality was bad enough but this king had the manners of a stableboy.

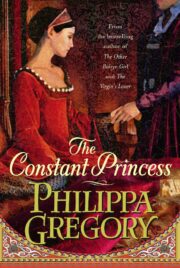

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.